Surgery in Mesopotamia

Origins of Mesopotamian surgery

Mesopotamian surgery has not been studied extensively in Assyriology. Articles on the topic often contain only isolated data points and generalised conclusions that surgery is lacking from Babylonian medical texts. But it is doubtful that surgery was not practiced in Mesopotamia, bearing in mind the evidence for it in contemporary Egypt. Meanwhile, Mesopotamian textual material has become ever more available. And we see many clues that a form of surgery was emerging there too. However, cuneiform texts do not reveal a word that we can translate as "surgery" or "surgeon." When a surgical intervention was needed, it was carried out by a person who also mixed drugs, applied bandages, prepared medications, potions, ointments, recited incantations, and performed rituals. In other words: in those days, the particular specialisation of the surgeon – so common nowadays – was not yet born. Its role was played by medical practitioners called asû or āšipu (also called mašmašu).

In order to trace back "surgical" information, we must go back to the basics of the word surgery. It originates from the Ancient Greek word χειρουργία, then borrowed into Latin chirurgia, from there introduced into European languages. Its basic meaning is the "hand-work", which is a common feature in healing practices everywhere. We will therefore look for evidence of healing interventions with instruments and/or by bare hands.

Texts don't reveal clear information about surgical topics such as anaesthesia, antiseptics, infections or death rate. But cuneiform texts do mention plants and minerals in conjunction with "hand-work" therapy. Unfortunately, the identification of drugs is far from certain. We can only guess at the identification of the plants and their chemical properties. Salt might have had antiseptic usage, but it is not always mentioned with the relevant therapies. In general, we do not see a cluster of drugs used before "hand-work" interventions, which we may interpret as anaesthesia. Infections were certainly common; when the body could not resist, death was probable. It is important to bear in mind that modern perceptions will not apply to Mesopotamian practices. There is no real information about sensitivity, pain, trust in the process, or expectations. The general attitude might be as different as between head surgery in a central European hospital today and common trepanation during the 20th century in Nigeria.

The "hand-work" of Gula

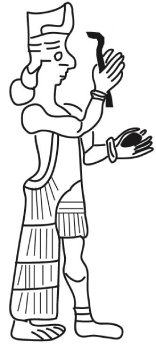

The iconography of the healing goddess Gula in the first millennium BCE shows how significant the "hand-work" in Mesopotamia must have been. The detailed drawing shows Gula standing upright, holding symbolic objects in both her hands. The object in her upper hand resembles a medical knife, and the oval object in her lower hand might symbolise a cuneiform tablet (Sibbing-Plantholt 2022).

Gula's image, presenting her "hand-work", referring to its importance in Mesopotamian healing. Panayotov's drawing from cylinder seal BM 89846.

These two symbols represent Gula's craft. The medical knife illustrates the significance of the "hand-work" in Mesopotamia. The tablet represents the empirical collection of cuneiform medical texts, as the source of healing knowledge.

Read more

Sibbing-Plantholt, I. 2022. The Image of Mesopotamian Divine Healers. Healing Goddesses and the Legitimization of Professional asûs in the Mesopotamian Medical Marketplace. Cuneiform Monographs 53. Leiden-Boston: Brill.

White, A. J., Herbeck, J, Scurlock, J., and Mayberry, J. in Press. "Ancient surgeons: A characterization of Mesopotamian surgical practices", in The American Journal of Surgery [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.03.047]

Strahil V. Panayotov

Strahil V. Panayotov, 'Surgery in Mesopotamia', The Nineveh Medical Project, The Nineveh Medical Project, Department of the Middle East, The British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG, 2022 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/asbp/NinMed/surgery/]