Cataloguing the Library

In 19th century few people were able to work with cuneiform tablets. In 1861 the Museum hired George Smith. He had been working as an engraver at a printing firm, but had dedicated his spare time to his passion for cuneiform. On frequent visits to the Museum, he convincingly demonstrated his abilities. Smith was tasked with re-joining the Library tablets that had been smashed in antiquity. Smith's skills led to his promotion to assistant grade, tasked with undertaking a systematic examination of the tablets. He began grouping tablets according to genre. Indeed, visitors would request – and be given – tablets according to genre until 1880's. Budge (1925)pp. 89-128 gives some details that show the logistical hurdles faced by Smith. At the time there was no artificial light in the Museum, and few lanterns. Curators were restricted by the limited daylight hours and hampered by the notorious London fogs of the day. Smith also faced space issues, being forced to surrender his working space when the accountants required it. We can only imagine the frustration he must have felt.

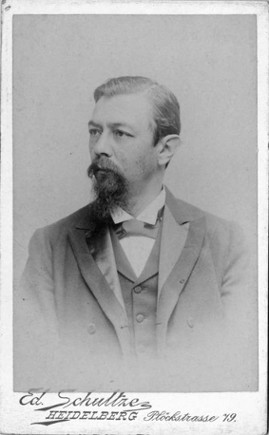

The task of registering, numbering and cataloguing the tablet collections was immense, and Smith's career was cut tragically short. In 1886 Peter Le Page Renouf (Keeper of Oriental Antiquities at the British Museum) injected extra resources to finish the task. The "Assistants" would ensure that all tablets would be registered and numbered. Further manpower was needed to write the catalogue. For that a talented young Bavarian scholar, Carl Bezold, was employed. Between 1889-1899 he described over 22,000 tablets over five volumes, and provided an index. The incredible quality of his work is proven by its longevity; it is still a valuable resource more than 100 years since its publication. The speed of this achievement is remarkable. There are 20th century excavations that have failed to match this pace, even with the assistance of modern technology.

- C. Bezold, Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum. Vol. I (London, 1889)

- C. Bezold, Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum. Vol. II (London, 1891)

- C. Bezold, Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum. Vol. III (London, 1893)

- C. Bezold, Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum. Vol. IV (London, 1896)

- C. Bezold, Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum. Vol. V (London, 1899)

The first cataloguer of the Nineveh tablets: Carl Bezold, in his carte de visite. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 [https://www.britishmuseum.org/terms-use/copyright-and-permissions]

Three supplementary volumes were later published by other authors:

- L.W. King, Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum. Supplement (London, 1914). This volume includes a few left- over tablets deriving from early excavations, tablets purchased since Bezold's work, and those excavated in recent seasons.

- W.G. Lambert and A. Millard, Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum. Second Supplement (London, 1968). This catalogues the tablets from the 1927-32 seasons.

- W.G. Lambert, Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection. Third Supplement (London, 1992). This contains thousands of very small fragments left over from various campaigns.

Thousands of fragments of Nineveh tablets have been re-joined over the years, and the rate of joining only continues to grow. Keeping track of these joins is an important element of cataloguing. Lists of joins were necessary already during the cataloguing process itself. Bezold (1893) p. vii and (1896) vii ff provides a list of fragments rejoined since the sheets of his catalogue were printed. This was supplemented by King (1914) appendix III. A separate volume was needed in 1960.

- Bateman, C. and Parsely, J., A List of Fragments Rejoined in the Kuyunjik Collection of the British Museum (London, 1960)

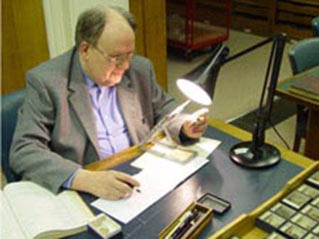

The name most associated with joining fragments is Riekele Borger, who made countless joins himself, and published lists of them for the benefit of colleagues. He also wrote about the joining process:

- R. Borger, "Ein Brief Sîn-idinnams von Larsa an den Sonnengott sowie Bemerkungen über 'Joins' und das 'Joinen'", in Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Philologisch-historische Klasse, Jahrgang 1991 Nr. 2): 37 - 81 (or: [1] - [45]).

There have been countless publications of Nineveh material. In 1964 Erle Leichty published a summary list of them:

- E. Leichty, A Bibliography of The Cuneiform Tablets of the Kuyunjik Collection in the British Museum (London, 1964)

Following him, Borger published a series of updates:

- R. Borger, "Anhang: Nachträge zu Leichty Bibliography", in Handbuch der Keilschriftliteratur I (Berlin and New York, 1975) pp. 651–659

- R. Borger, "Zur Kuyunjik-Sammlung. Nachträge zu HKL II, S. 331 – 395", in Archiv für Orientforschung 25 (1974-77) pp. 411–413

- R. Borger, "Anhang: zur Kuyunjik-Sammlung", in Handbuch der Keilschriftliteratur II (Berlin and New York, 1975) pp. 331–395

- R. Borger, "Die Kuyunjik-Sammlung von Ende 1973 bis Anfang 1982. Nachträge zu Leichty's Bibliography und zu HKL II 331 – 395", in Archiv für Orientforschung 28 (1981-82) pp. 365–394

- R. Borger, "Die Kuyunjik-Sammlung 1982–1983. Nachträge zu Leichty's Bibliography, HKL II 331–395 und AfO 28, 365–394", in Archiv für Orientforschung 31 (1984) pp. 331–336

Riekele Borger at work in the Arched Room at the British Museum. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 [https://www.britishmuseum.org/terms-use/copyright-and-permissions]

A new effort to update and improve the catalogue came with the birth of the Ashurbanipal Library Project in 2002. Its initial aim was to bring the catalogue up-to-date, making clear which tablets remained to be studied. In 2006 Jeanette Fincke was appointed to catalogue the portion of the collection written in Babylonian script. Subsequently, a collaboration was formed with Borger. For many years this meticulous scholar had been identifying tablets and transliterating fragments. Sadly he wasn't able to complete his work, passing away suddenly in 2010. His notes form a valuable contribution to the catalogue. Since then, cataloguing has been undertaken by Jon Taylor, with the collaboration of colleagues and volunteers. In particular, the team at the electronic Babylonian Literature project (University of Munich) have contributed many identifications, joins, and transliterations.

Jonathan Taylor

Jonathan Taylor, 'Cataloguing the Library', Ashurbanipal Library Project, The Ashurbanipal Library Project, Department of the Middle East, The British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG, 2022 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/asbp/recordingthelibrary/cataloguingthelibrary/]