Recording the Library

Almost all tablets yet excavated from Ashurbanipal's Library are in the British Museum collection.

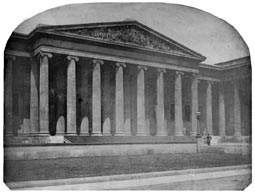

The British Museum in 1840's-50's

The excavations at Nineveh in late 1840's-early 1850's marked a revolution. The Assyrian sculptures amazed the world, and the tablets gave the ancients back their voice. Until then there were very few tablets (or indeed other Mesopotamian objects) in the collections either of the British Museum or elsewhere (Pallis 1956 pp. 64-69 provides a list of what was available to scholarship). Now suddenly there were thousands. The remarkable discovery of the Library at Nineveh confronted the Museum with significant logistical problems: in conservation, storage, registration, cataloguing and publication. The sheer size of the Nineveh corpus is such that it alone matches, and in most cases exceeds, the major European and American collections even today. Published catalogues are still lacking for most of these other collections. And the tablets themselves brought new challenges, such as how to conserve and store unfired clay objects. Here, as with many other tasks, Museum staff were among the first to face these issues, and they pioneered the solutions.

The British Museum in 1857. Photo by Roger Fenton.

In 1840's, archaeology as a discipline had not been invented. The field of Assyriology was also yet to be born. Both excavation and research were conducted largely by individuals using their free time outside their jobs, or by those working in Biblical studies, for example. Scholars had not yet learned how to utilise the detailed archaeological context of finds, and excavation techniques and records of the time thus yield relatively little information. Layard's excavations had begun as a private initiative financed by Stratford Canning, British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. The success of his first expedition finally convinced the Museum, and more importantly the Treasury, to take over sponsorship of the excavations in 1846. Finds from each excavation season were sent to Britain in separate shipments. Having arrived at the Museum, shipments were not kept rigorously apart. The sudden arrival of so many tablets was unexpected and posed problems for the Department of Antiquities, as it then was. The Museum was still primarily a library, hence the title "Principal Librarian" given to its principle executive (the British Library was created only in 1973). The Antiquities department was responsible for all antiquities from around the world. It was counterpart to the Natural History Department (the natural history collections moved to a new building in 1881, still under the charge of the Trustees).

The arrival of Assyrian antiquities at the British Museum captured the public imagination. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 [https://www.britishmuseum.org/terms-use/copyright-and-permissions]

The Museum, established as a public body, relied on funding from the Treasury. Yet funds were scarce at the best of times. 1848 was a year of revolutions across Europe, and 1853 saw the start of the Crimean War. Finances were particularly tight. There were few staff available to process the new material. Yet in 1860 the significance of the antiquities department was recognised, and three new departments were formed from it. One of those was the Department of Oriental Antiquities, responsible for pre-Greek civilisations, primarily Egyptian and Assyrian.

Jonathan Taylor

Jonathan Taylor, 'Recording the Library', Ashurbanipal Library Project, The Ashurbanipal Library Project, Department of the Middle East, The British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG, 2022 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/asbp/recordingthelibrary/]