You are seeing an unstyled version of this site. If this is because you are using an older web browser, we recommend that you upgrade to a modern, standards-compliant browser such as FireFox [http://www.getfirefox.com/], which is available free of charge for Windows, Mac and Linux.

Neo-Assyrian Archival Texts from Guzana

The city of Guzana (modern Tell Halaf) lies in the eastern part of the fertile triangle formed by the tributaries of the Khabur river. In the early first millennium BC, Guzana was the capital of the regional kingdom of Bit-Bahiani ("House of Bahianu", after the founding father of the ruling dynasty) before the area was integrated into the Assyrian Empire as the province of Guzana during the reign of Ashurnasirpal II (882–859 BC).

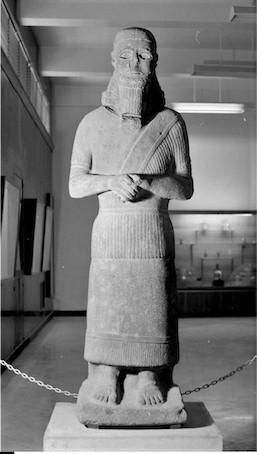

The so-called Fekheriyeh Statue of Adda-it'i, governor of Guzana, as displayed in the National Museum of Damascus. Photo credit: Wayne Pitard. The image is available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication [https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en].

At that time, the Assyrian administration in the newly established western provinces still greatly relied on individuals of local extraction. This is best demonstrated by the life-sized stone statue of Adda-it'i [/riao/theassyrianempire883745bc/ashurnasirpalii/texts10012007/index.html#ashurnasirpal22004], the governor of Guzana, which was created as an offering to the temple of the storm-god of Sikani (modern Tell Fekheriyeh [http://www.fecheriye.de/]) and inscribed on its front with a cuneiform text in Akkadian [/riao/Q004602/] and on its reverse with the same text in alphabetic Aramaic. These two versions have small differences, and very significantly, Adda-it'i calls himself and his father and predecessor Šamaš-nuri [/saao/saas2/Q004243.45#Q004243.40] (who served as the Assyrian year eponym for the year 866 BC) "king of Guzana" in the Aramaic version of the text and "governor of Guzana" in the Akkadian version. Later on, the Assyrian state administration generally preferred to appoint as provincial governors [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/governors/] officials who had been educated at the imperial palace and who had no previous link to the region.

Tell Halaf [http://www.grabung-halaf.de/index.php?l=eng] was one of the very first archaeological sites to be systematically excavated in what is today Syria. The settlement mound came to the notice of Max von Oppenheim in 1899, during his time as a German diplomat posted in Cairo. After leaving the foreign service, he explored the site for three years, from 1911–13, using his family's private funds to finance his large-scale excavations: He especially concentrated on unearthing the palace of king Kapara of Bit-Bahiani, constructed in the early first millennium BC and richly decorated with stone statues and reliefs. The First World War and the subsequent economic crisis prevented Oppenheim's return until 1927, when he was finally able to recover the large sculptures that he had stored in his excavation house and brought them to Berlin; he subsequently undertook another excavation campaign in 1929. In order to exhibit his finds, he opened the Tell Halaf Museum in Berlin in 1930.

In the course of an air raid during the Second World War, Oppenheim's museum was destroyed in 1943, and with it the precious monuments, which burst into thousands of pieces in the subsequent fire. From 2001–10, Lutz Martin of the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin directed a restoration project that managed to reconstruct the monumental Tell Halaf sculptures from about 27,000 fragments. This also prompted new excavations at the site, which he co-directed with 'Abd al-Masih Bagdo (Hasseke Directorate of Antiquities) and Mirko Novák (now University of Bern) from 2006–10. As part of these excavations, the so-called Northeast Palace was investigated again where Oppenheim had found the archive of the Assyrian governor Mannu-ki-Aššur from the early eighth century BC; but only one new tablet and a few fragments were discovered.

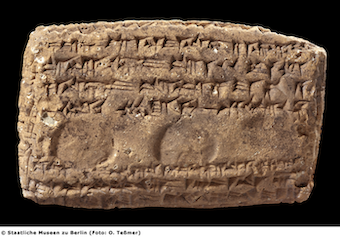

Tablets from the archive of Mannu-kī-Aššur discovered during Max von Oppenheim's excavations at Tell Halaf. Photo credit: O. Teßmer, for the Tell Hallaf Ausgrabungsprojekt [http://www.grabung-halaf.de/currenttexts.php?l=eng].

In addition to the governor's archive, which gives rare insight into the Assyrian state and provincial administration during the reign of Adad-nerari III (810–783 BC), a ceramic vessel with a small archive of Assyrian and Aramaic texts, whose central figure is a man called Il-manani, was discovered. This archive dates to the very last years of the Assyrian occupation of Guzana, when the Assyrian heartland had already been lost to the Babylonian and Median forces, with the capture of Assur and Nineveh in 614 BC and 612 BC respectively. The remaining members of the royal court withdrew to the west, where the city of Harran became the last rallying point of the Assyrian Empire.

A tablet from the archive of Il-manani discovered during Max von Oppenheim's excavations at Tell Halaf. Photo credit: O. Teßmer, for the Tell Hallaf Ausgrabungsprojekt [http://www.grabung-halaf.de/currenttexts.php?l=eng].

Three legal documents from Il-manani's archive are dated by the eponym year Nabû-mar-šarri-uṣur, the very last Assyrian commander-in-chief (Akkadian turtānu). This man's direct predecessor was Šamaš-šarru-ibni (meaning "The god Šamaš created the king"), who presumably died with his king Sîn-šarru-iškun during the three-month siege of Nineveh in 612 BC. Nabû-mar-šarri-uṣur served Assyria's final ruler Aššur-uballiṭ II, who had to claim the throne in Harran, rather than at Assur in the temple of the god Aššur, as tradition demanded. The name of Aššur-uballiṭ's commander-in-chief's means "O god Nabû, protect the crown prince!," which is highly unusual. Names of this general type were very common in Assyrian onomastics and they were especially popular among state officials. However, these types of names usually referred to their lord, the king, and not to the crown prince. After the loss of the city of Assur and the death of king Sîn-šarru-iškun, the last Assyrian king to rule from the Assyrian heartland, Nabû-mar-šarri-uṣur, the new commander-in-chief, must have adapted his name to suit the unusual circumstances of Assyria having the crown prince Aššur-uballiṭ as ruler, a man not a properly crowned as king in the Aššur temple at Assur.

Click here [/atae/guzana/pager] to browse the Guzana corpus.

The aim of the Guzana sub-project of ATAE is to make the published Neo-Assyrian archival texts from Tell Halaf available online for free in a fully searchable and richly annotated (lemmatized) format, as well as to widely disseminate, facilitate, and promote the active use of these important cuneiform sources in academia and beyond. ATAE/Guzana presently includes Neo-Assyrian sources edited and discussed in the following publications:

Cover of Dornauer, Das Archiv des assyrischen Statthalters Mannu-kī-Aššūr von Gūzāna/Tall Ḥalaf [https://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de/Das_Archiv_des_assyrischen_Statthalters_Mannu-ki-Aššur_von_Guzana_/Tell_Halaf/titel_2046.ahtml].

- A. Dornauer, Das Archiv des assyrischen Statthalters Mannu-kī-Aššūr von Gūzāna/Tall Ḥalaf (Vorderasiatische Forschungen der Max Freiherr von Oppenheim-Stiftung 3/3; click here [https://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de/Das_Archiv_des_assyrischen_Statthalters_Mannu-ki-Aššur_von_Guzana_/Tell_Halaf/titel_2046.ahtml] to buy the book), Wiesbaden, 2014;

- J. Friedrich, A. Ungnad, G.R. Meyer, and E.F. Weidner, Die Inschriften vom Tell Halaf (Beiheft zum Archiv für Orientforschung 6), Berlin, 1940;

- A. Fuchs and W. Röllig, "Die neuen Schriftfunde von Tell Halaf," in: A.M.H. Baghdo, L. Martin, M. Novák, and W. Orthmann (eds.), Ausgrabungen auf dem Tell Halaf, Teil II: Vorbericht über die dritte bis fünfte syrisch-deutsche Grabungskampagne auf dem Tell Halaf (Vorderasiatische Forschungen der Max Freiherr von Oppenheim-Stiftung 3/2; click here [https://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de/Tell_Halaf:_Vorbericht_über_die_dritte_bis_fünfte_syrisch-deutsche_Grabungskampagne/titel_4347.ahtml] to buy the book), Wiesbaden, 2012: 211–214; and

- K. Radner,"Last emperor or crown prince forever? Aššur-uballiṭ II of Assyria according to archival sources," [https://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/62014/] in: S. Yamada (ed.), Neo-Assyrian Sources in Context: Thematic Studies of Texts, History and Culture (State Archives of Assyria Studies 28), Helsinki, 2018: 135–142.

ATAE is a key component of the Archival Texts of the Middle East in Antiquity (ATMEA) sub-project of the LMU-Munich-based Munich Open-access Cuneiform Corpus Initiative [https://www.en.ag.geschichte.uni-muenchen.de/research/mocci/index.html] (MOCCI; directed by Karen Radner and Jamie Novotny). Funding for the ATAE corpus project has been provided by LMU Munich and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (through the establishment of the Alexander von Humboldt Chair for Ancient History of the Near and Middle East).

For further details, see the "About the project" [/atae/abouttheproject/index.html] page.

Home Page banner credit

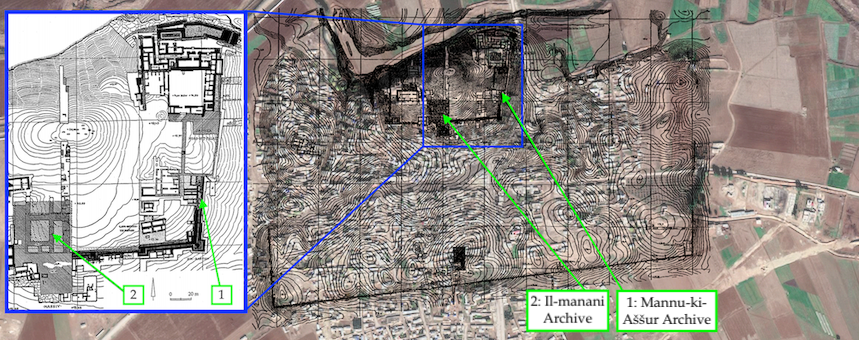

Satellite image of the ruins of Guzana overlaid with a general plan of the city and the location of the archives of Mannu-kī-Aššur and Il-manani (Pedersén, Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East 1500-300 B.C. pp. 173–174 plans 82–83). Image prepared by Jamie Novotny.

Karen Radner

Karen Radner, 'Neo-Assyrian Archival Texts from Guzana', Neo-Assyrian Archival Texts from Guzana, The ATAE/Guzana Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2023 [http://oracc.org/guzana/]