You are seeing an unstyled version of this site. If this is because you are using an older web browser, we recommend that you upgrade to a modern, standards-compliant browser such as FireFox [http://www.getfirefox.com/], which is available free of charge for Windows, Mac and Linux.

Neo-Assyrian Archival Texts from Kalhu

Satellite image of the citadel of Kalhu (modern Nimrud) overlaid with a plan of its palaces and temples and their archives (Pedersén, Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East 1500-300 B.C. p. 148 Plan 68). Image prepared by Jamie Novotny.

In the first millennium BC, Kalhu (modern Nimrud, biblical Calah) was one of the most important cities of the Assyrian Empire. But the site was already inhabited in the 6th millennium BC and, from at least the early second millennium BC, was one of the foremost northern Mesopotamian centers, then known under the name Kawalhum or Kawilhum. In the second half of second millennium BC, during the Middle Assyrian Period, Kalhu was a provincial capital, a status that it held until the collapse of the Assyrian Empire at the end of the 7th century BC.

Until the reign of the ninth-century-BC king Ashurnasirpal II [/riao/theassyrianempire883745bc/ashurnasirpalii/index.html] (r. 883–859 BC), the religious and ideological center of Assyria, the city of Assur [/atae/assur/], served also as the king's main residence. Ashurnasirpal, however, relocated the entire royal court, moving hundreds of people under the supervision of his palace superintendent Nergal-apil-kumuya to Kalhu after this ancient city had been completely transformed. The old settlement mound, having grown to a substantial height in the course of its five-thousand-year-long occupation, was turned into a citadel that housed only the royal palace and several temples of the most important deities of Assyria, such as Ninurta and Ištar — but not a shrine for the national Aššur, whose only sanctuary remained in the holy city of Assur. The citadel was protected by its own fortification walls but occupied only a small part in the south-western corner of the larger city: with a size of about 360 hectares, Ashurnasirpal 's Kalhu covered twice the area of Assur and was surrounded by a 7.5-km-long fortification wall.

Kalhu served as the main residence of all Assyrian kings up to the eighth-century-BC ruler Tiglath-pileser III [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/kings/tiglatpileseriii/] (r. 744–727 BC) but, while Ashurnasirpal's palace [/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thecity/northwestpalace/index.html] (to so-called "Northwest Palace") was not abandoned, several of his successors built their own palaces in Kalhu, among them Adad-nārārī III [/riao/theassyrianempire883745bc/adadnarariiii/index.html] (r. 810–783 BC). When Tiglath-pileser's son and second successor, Sargon II [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/kings/sargonii/] (r. 721–705 BC), moved the court and central administration to Dur-Šarruken [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/cities/durarruken/] in 706 BC, Kalhu's time as the political and administrative center of the Assyrian Empire came to an end after more than a century and a half. Although the city never again became the primary residence of Assyria's kings, it remained, however, a vital administrative, military, and religious center until the fall of the Assyrian Empire, when it was twice sacked and destroyed. The once-grand Assyrian capital, however, was not completely abandoned but, while there is evidence for its continued habitation until the Hellenistic Period, Kalhu was no longer an important city: when Xenophon and his Greek mercenaries passed by the site, then known as Larissa, at the close of the 5th century BC, it lay in ruins and was inhabited only by squatters who had taken refuge in the remains of what must be the ziggurat of the Ninurta temple [/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thecity/zigguratandtemples/index.html].

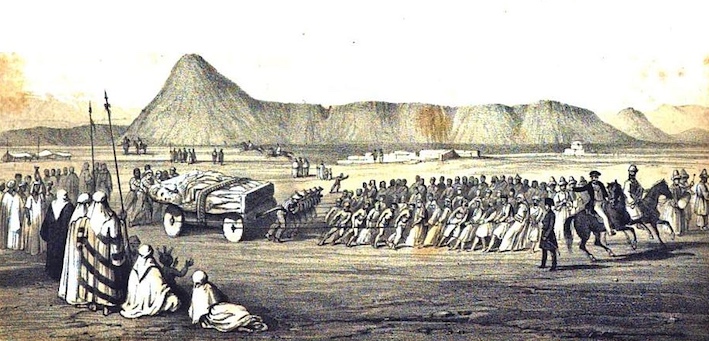

Frontispiece of Nineveh and its Remains, by Austen Henry Layard, 1849. Sketch of A.L. Layard's expedition transporting a human-headed bull colossus, showing the ruins of ancient Kalhu and its ziggurat in the background. Image credit: Public Domain.

Kalhu — which is situated in the center of a triangle [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/countries/centralassyria/] formed by the three most important cities of central Assyria: Assur in the south, Nineveh in the north and Arbela in the east — lies on the eastern bank of the Tigris, near its convergence with the Greater Zab, and held an important position in the long-distance traffic network, both over land and on the rivers. This important Assyrian administrative and religious center was not only an important stop on the north-south route along the Tigris, but it also controlled a key route leading east via Arbela towards the Zagros Mountains and, along their western fringes, south into Babylonia. Its archaeological remains have been the subject of investigation since the 1840s — when Austen Henry Layard excavated sections of the Northwest Palace and Southwest Palace by tunneling along the edges of walls lined with inscribed and sculptured wall panels — and it is one of the first Assyrian and Babylonian cities to be systematically explored.

For further information about the ancient and modern history of Kalhu, as well as its most important buildings and artifacts, see the Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production [/nimrud/index.html] Project and the essay "Kalhu, Tiglath-pileser's royal residence city" [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/cities/kalhu/] on the Assyrian Empire Builders [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/] website.

While excavations in the course of the 19th century resulted in the discovery of only a single cuneiform tablet (presumably because unfired clay tablets were not recognized by excavators), Kalhu yielded a number of important textual finds in the 20th century, under the direction of Sir Max Mallowan, with the discovery of the so-called Nimrud Letters in 1952 constituting a particular highlight. Since Layard's initial excavations of this once-flourishing Assyrian city in 1845, 175 years ago, several hundred of clay tablets inscribed with Neo-Assyrian archival texts (including correspondence between the Assyrian king and important officials) have been unearthed, with the bulk of the finds housed in the British Museum in London and the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. These texts, most of which were written in the Neo-Assyrian dialect of Akkadian, were discovered in various rooms and buildings of the Kalhu's citadel, located in the southwest corner of the city, and in "Fort Shalmaneser [/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thecity/fortshalmaneser/index.html]," the armory built by Shalmaneser III [/riao/theassyrianempire883745bc/shalmaneseriii/index.html] (r. 858–824 BC) in the southeast corner. This varied eighth- and seventh-century-BC material more or less originate from at least seventeen different archival contexts. Following Olof Pedersén's designations, these are:

Satellite image of the ruins of Kalhu (modern Nimrud) overlaid with a general plan of the archives and libraries (Pedersén, Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East 1500-300 B.C. p. 144 Plan 66). Image prepared by Jamie Novotny.

- 1 — Fort Shalmaneser, NE 47-50

- 2 — Fort Shalmaneser, SW 6

- 3 — Fort Shalmaneser, Palace Manager Archive (SE 1, SE 10)

- 4 — Fort Shalmaneser, SE 14-15

- 5 — Fort Shalmaneser, šakinutu Archive (S 10)

- 6 — Northwest Palace, ZT 4

- 7 — Northwest Palace, ZT 30-31

- 8 — Northwest Palace, Room HH

- 9 — Northwest Palace, Room 57

- 10 — Northwest Palace, Room AB (well)

- 11 — Northwest Palace, ZT 13-17

- 12 — Governor's Palace

- 13 — Burnt Palace

- 14 — Nabû Temple, NT12-14

- 15 — Nabû Temple, Throne Room

- 16 — Nabû Temple, NT16

- 17 — Šamaš-šarru-uṣur Archive

A PDF of Olof Pedersén, Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East 1500-300 B.C. can be downloaded here [http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:88568/FULLTEXT01.pdf]

Click here [/atae/kalhu/pager] to visit the ATAE/Kalhu corpus, this link [/atae/] to visit the Main ATAE Portal, or this link [/atae/pager] to browse the entire ATAE corpus.

The aim of the Kalhu sub-project of ATAE is to make the published archival texts from Nimrud available online for free in a fully searchable and richly annotated (lemmatized) format, as well as to widely disseminate, facilitate, and promote the active use of these important cuneiform sources in academia and beyond. ATAE/Kalhu presently includes Neo-Assyrian sources edited in the following publications:

- CTN 1 [/atae/ctn1/] = J.V. Kinnier Wilson, The Nimrud Wine Lists (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 1), London, 1972

- CTN 2 [/atae/ctn2/] = J.N. Postgate, The Governor's Palace Archive (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 2), London, 1973

- CTN 3 [/atae/ctn3/] = S. Dalley and J.N. Postgate, The Tablets from Fort Shalmaneser (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 3), London, 1984

- CTN 6 [/atae/ctn6/] = S. Herbordt, R. Mattila, B. Parker(†), J.N. Postgate and D.J. Wiseman(†), Documents from the Nabu Temple and from Private Houses on the Citadel (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 6), London, 2019

- Edubba 10 [/atae/edubba10/] = A.Y. Ahmad and J.N. Postgate, Archives from the Domestic Wing of the North-West Palace at Kalhu/Nimrud (Edubba 10), 2007

- SAA 01 [/saao/saa01/] = S. Parpola, The Correspondence of Sargon II, Part I: Letters from Assyria and the West (State Archives of Assyria 1), Helsinki 1987

- SAA 02 [/saao/saa02/] = S. Parpola and K. Watanabe, Neo-Assyrian Treaties and Loyalty Oaths (State Archives of Assyria 2), Helsinki 1988

- SAA 05 [/saao/saa05/] = G. B. Lanfranchi and S. Parpola, The Correspondence of Sargon II, Part II: Letters from the Northern and Northeastern Provinces (State Archives of Assyria 5), Helsinki 1990

- SAA 12 [/saao/saa12/] = L. Kataja and R. Whiting, Grants, Decrees and Gifts of the Neo-Assyrian Period (State Archives of Assyria 12), Helsinki, 1995

- SAA 15 [/saao/saa15/] = A. Fuchs and S. Parpola, The Correspondence of Sargon II, Part III: Letters from Babylonia and the Eastern Provinces (State Archives of Assyria 15), Helsinki 2001

- SAA 19 [/saao/saa19/] = M. Luukko, The Correspondence of Tiglath-pileser III and Sargon II from Calah/Nimrud (State Archives of Assyria 19), Helsinki 2012

- SAA 20 [/saao/saa20/] = S. Parpola, Royal Rituals and Cultic Texts (State Archives of Assyria 20), Winona Lake, IN, 2017

Click here [/atae/kalhu/pager] to visit the ATAE/Kalhu corpus.

ATAE is a key component of the Archival Texts of the Middle East in Antiquity (ATMEA) sub-project of the LMU-Munich-based Munich Open-access Cuneiform Corpus Initiative [https://www.en.ag.geschichte.uni-muenchen.de/research/mocci/index.html] (MOCCI; directed by Karen Radner and Jamie Novotny). Funding for the ATAE corpus project has been provided by LMU Munich and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (through the establishment of the Alexander von Humboldt Chair for Ancient History of the Near and Middle East).

For further details, see the "About the project" [/atae/abouttheproject/index.html] page.

Karen Radner & Jamie Novotny

Karen Radner & Jamie Novotny, 'Neo-Assyrian Archival Texts from Kalhu', Neo-Assyrian Archival Texts from Kalhu, The ATAE/Kalhu Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2023 [http://oracc.org/atae/kalhu/]