You are seeing an unstyled version of this site. If this is because you are using an older web browser, we recommend that you upgrade to a modern, standards-compliant browser such as FireFox [http://www.getfirefox.com/], which is available free of charge for Windows, Mac and Linux.

Neo-Assyrian Archival Texts from Til-Barsip

In the early first millennium BC, the ancient city buried in the settlement mound of Tell Ahmar (Arabic "Red mound") was known under three names: In Luwian contexts, its name was Masuwari, its Aramaic designation was Til-Barsip, and, once the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III [/riao/theassyrianempire883745bc/shalmaneseriii/index.html] (858–824 BC) conquered the city in 856 BC and integrated it into the provincial system, he changed its name to Kar-Salmanu-ašared. The Luwian name fell gradually out of use under Assyrian domination, and the last known mention dates to the 8th century BC. It is found in the trilingual Luwian-Aramaic-Assyrian inscription of Ninurta-belu-uṣur, the Assyrian governor of Kar-Salmanu-ašared who rebuilt the city wall of Hadattu (modern Arslan Tash [https://www.hittitemonuments.com/arslantas2/]) and used the title "country-lord of Masuwari" in the Luwian version of the text. However, the Aramaic designation Til-Barsip continued to be used side-by-side with the new Assyrian name and is attested long after the end of the Assyrian Empire, as it appears as Bersiba (Βερσίβα) in Ptolemy's Geography (2nd century AD).

The Assyrian name Kar-Salmanu-ašared "The Harbour of Shalmaneser" refers not only to Til-Barsip's conqueror but also to the city's important role in the shipping route along the Euphrates. It was located on the eastern bank of the Euphrates, just opposite of the spot where this river is joined by its tributary Sajur. The Sajur river has its headwaters in the region of the Turkish city of Gaziantep and thus provides a comfortable connection from the Euphrates valley to inner Anatolia.

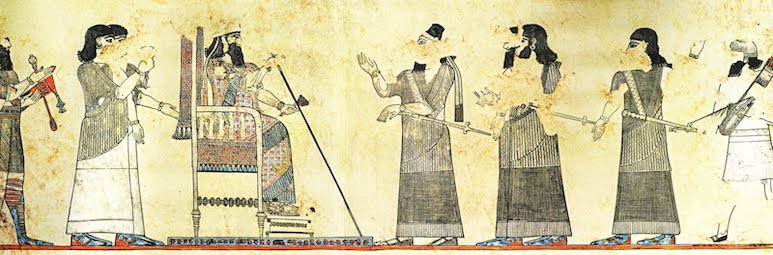

Scene of the wall paintings decorating the Assyrian palace of Til-Barsip, probably from the reign of Tiglath-pileser III (744–727 BC). The king, seated on a throne with the typical footstool, receives Assyrian dignitaries and soldiers who are being introduced by the crown prince, easily recognisable because of the typical ribbon he wears around his head. Image source: Wikimedia Commons [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tell_Ahmar,_mural_palacio_rey_Tiglatpileser_audiencia_sicglo_VIII.jpg].

Prior to the Assyrian conquest, Til-Barsip had been the capital of the regional kingdom of Bit-Adini ("House of Adinu", referring to the founding father of the ruling dynasty), which controlled the lands south of the Taurus mountains encircled by the large eastwards bend of the Euphrates and demarcated in the east by its tributary, the river Balikh. After 856 BC, this region became the Border March of the Commander-in-Chief (Assyrian turtānu), the westernmost frontier of the Assyrian Empire until Tiglath-pileser III [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/kings/tiglatpileseriii/] (744–727 BC) began the wars of conquest that would bring the eastern Mediterranean coast under his direct control. As a consequence, and at the latest during the reign of Sargon II [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/kings/sargonii/] (724–705 BC), the larger territory hitherto governed by the Commander-in-Chief was split into several smaller administrative units, and the province of Til-Barsip / Kar-Shalmaneser was one of them.

The stele of Aššur-dur-paniya, the Assyrian governor of Kar-Shalmaneser, dedicated to his lady, the goddess goddess Ištar of Arbela (Louvre, AO 11503). This image [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stele_of_Ishtar-AO_11503-IMG_7740-white.jpg] by Rama is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 France license.

To this time dates a stone stele now kept in the Louvre (AO 11503) that depicts the goddess Ištar of Arbela on her sacred animal, the lion, and bears a dedication of Aššur-dur-paniya, the governor of Kar-Shalmaneser. This monument was among the objects excavated at Til-Barsip by a French archaeological mission directed by François Thureau-Dangin from 1929 to 1931. Another famous discovery of the period of Assyrian occupation is the fragmentary victory stele [/rinap/Q003326] of king Esarhaddon [/rinap/rinap4] (680–669 BC). Most importantly, Thureau-Dangin's team excavated a palace with very well preserved, multi-coloured wall paintings and a rich inventory, including many intricately carved ivory inlays that once decorated wooden pieces of furniture. These early excavations did not yield any clay tablets.

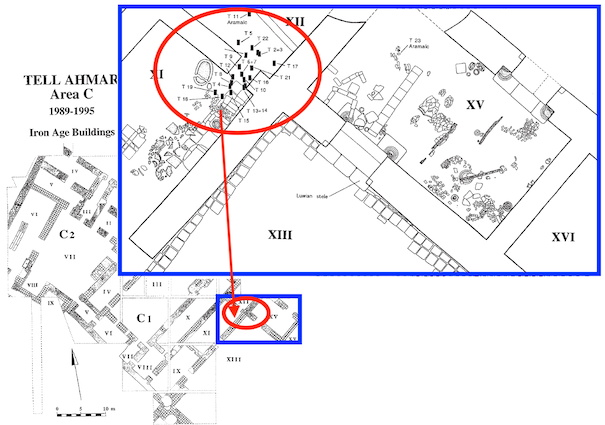

More recently, a Belgian-Australian team headed by Guy Bunnens and Arlette Roobaert-Bunnens excavated at Til Barsip from 1988 until 2010, and this work resulted in the discovery of clay tablets: Twenty-two Neo-Assyrian documents, as well as two Aramaic texts, were excavated in the debris of Building C1 at the western edge of the city in 1992 and 1993. All texts were published in 1997, with the inner tablet of one of these documents (no. T20a [/atae/tilbarsip/P522610.23#P522610.18]) published in 2004 after its envelope had been opened in the Archaeological Museum of Aleppo, where these tablets are kept. Til-Barsip is always spelled URU.tar-bu-si-ba in these texts, one of many variant spellings attested for this place in the Neo-Assyrian documentation.

Although the clay tablets were demonstrably not found in their original storage place but in a layer of debris, this material seems nevertheless to constitute one archive that centres on a man called Hannî. The earliest text (no. T15 [/atae/tilbarsip/P522606]) dates to 683 BC in the late reign of Sennacherib [/rinap/rinap3] (704–681 BC) but the majority of the documents fall into the reign of Ashurbanipal [/rinap/rinap5] (668–ca. 631 BC). Hannî issued various debt notes for silver sums (nos. T2, T4, and T6 [/atae/tilbarsip/P522593,P522595,P522597]) and bought slaves (nos. T8 and T9 [/atae/tilbarsip/P522599,P522600]); he is also mentioned in a legal agreement issued by the deputy governor of Til-Barsip and his scribe (no. T14 [/atae/tilbarsip/P522605]) that obliged Hannî and another man called Hašana to refrain from speaking to any of the local officials of Til-Barsip until a written order from the palace had arrived – clearly, they were involved in a sensitive matter and we would like to know much more. Among the other people attested in this small archive, the most interesting one is an anonymous "harem governess" (Assyrian šakintu), the female official in charge of the palace's women's quarters, who bought a slave (no. T13 [/atae/tilbarsip/P522604]). Her relationship to Hannî is unclear to us, but there was very likely either a professional or familial connection between them.

Click here [/atae/tilbarsip/pager] to browse the Til-Barsip corpus.

The aim of the Til-Barsip sub-project of ATAE is to make the published Neo-Assyrian archival texts from Tell Ahmar available online for free in a fully searchable and richly annotated (lemmatized) format, as well as to widely disseminate, facilitate, and promote the active use of these important cuneiform sources in academia and beyond. ATAE/Til-Barsip presently includes Neo-Assyrian sources edited and discussed in the following two publications:

- P. Bordreuil and F. Briquel-Chatonnet, "Aramaic Documents from Til Barsib," Abr-Nahrain 34 (1996–97): 100–107.

- G. Bunnens, "The Archaeological Context," Abr-Nahrain 34 (1996–97): 61–65.

- G. Bunnens, Tell Ahmar on the Syrian Euphrates: From the Chalcolithic Village to Assyrian Provincial Capital, Oxford, 2022, pp. 135–143, 157–164, and 171–172.

- S. Dalley, "Neo-Assyrian Tablets from Til Barsib," Abr-Nahrain 34 (1996–97): 66–99; and

- K. Radner, "A Neo-Assyrian Tablet from Til Barsib," Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires 2004/1: 25–27 no. 26.

Plan of Tell Ahmar Area C, with Buildings C1 and C2, showing the location of the twenty-two Neo-Assyrian documents and Aramaic texts discovered in 1992 and 1993. Image prepared by Jamie Novotny from Bunnens, Abr-Nahrain 34 (1996–97) figs. 1–2.

ATAE is a key component of the Archival Texts of the Middle East in Antiquity (ATMEA) sub-project of the LMU-Munich-based Munich Open-access Cuneiform Corpus Initiative [https://www.en.ag.geschichte.uni-muenchen.de/research/mocci/index.html] (MOCCI; directed by Karen Radner and Jamie Novotny). Funding for the ATAE corpus project has been provided by LMU Munich and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (through the establishment of the Alexander von Humboldt Chair for Ancient History of the Near and Middle East).

For further details, see the "About the project" [/atae/abouttheproject/index.html] page.

Home Page banner credit

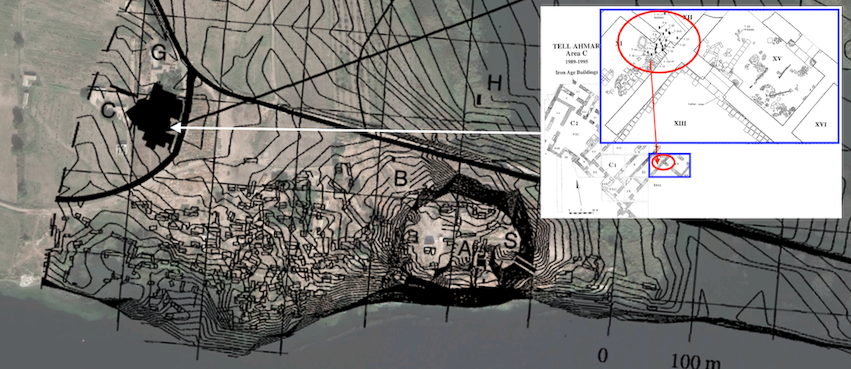

Satellite image of the ruins of Til-Barsip overlaid with a general plan of the city and a plan of Buildings C1 and C2, showing the location of an archive belonging to Hanni. Image prepared by Jamie Novotny from Bunnens, Abr-Nahrain 34 (1996–97) figs. 1–2 and Pedersén, Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East 1500-300 B.C. p. 176 plan 84.

Karen Radner

Karen Radner, 'Neo-Assyrian Archival Texts from Til-Barsip', Neo-Assyrian Archival Texts from Til-Barsip, The ATAE/Til-Barsip Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2023 [http://oracc.org/tilbarsip/]