Argišti I, son of Minua

Argišti, Inušpua and the line of succession

In his inscriptions, Argišti calls himself "son of Minua" (or "descendant of Minua"). From this, one might conclude that Argišti was Minua's immediate successor. Some earlier inscriptions, however, suggest that Argišti was not initially intended to be Minua's successor, but that his brother Inušpua was. How Argišti came into power is unclear. It cannot be excluded that he usurped the throne. It might, however, also be the case that Inušpua died young, probably before or soon after his ascession to the throne (for a more detailed discussion of this, see the portal page "Išpuini, Minua, and Inušpua").

Map showing the distribution of the stone inscriptions of Argišti I, in: Mirjo Salvini, CTU I: 344

Royal Titles

Argišti, son of Minua, mighty king, great king, king Bia lands, king of kings, lord of the city Ṭušpa. (CTU A 8-1, obv. ll. 4-6)

The first annals in Urartian history

Among the Urartian rulers, Argišti was the first to have authored annalistic inscriptions that chronicled his annual military campaigns and their outcomes as well as major building projects. In Urartian history, such annals are only known from Argišti and his son Sarduri.

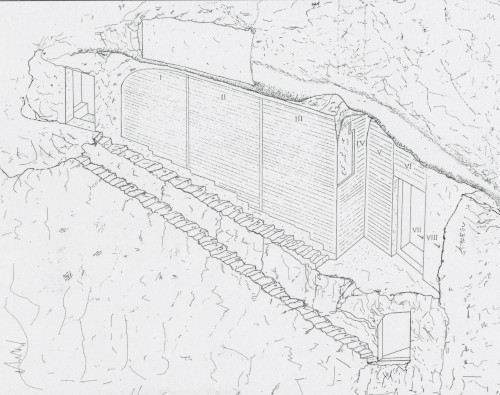

Argišti I's most detailed annalistic inscription is engraved on the entrance of his mausoleum, the rock chamber of Horhor in the southern cliff face of rock Van (A 8-3 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/ecut/Q007004]). The nearby rock-cut tomb was probably once Argišti's burial place.

The caves of Horhor (Van Kalesi), photo: Köroğlu, Kemalettin and Erkan Konyar (eds.): Urartu: Doğu'da Değişim / Transformation in the East, İstanbul 2011: 209

Sketch of the Annals of Argišti I (Van Kalesi) by A. Mancini, in: Mirjo Salvini, CTU III: 200.

The inscription is the longest Urartian text so far known and belongs to the most beautifully and meticuously engraved inscriptions. Unfortunately, the beginning of the text is lost. However, it is possible restore this lost text on the basis of a fragmentarily preserved inscription which was also composed by Argišti and is engraved on a stele found in the church Surp Sahak in Van (A 08-01 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/ecut/Q007002]).

Both texts clearly refer to the same events. Inscription A 08-01 is, however, much shorter and less detailed than the Horhor annals, which presumably were composed at the end of Argišti's reign.

These annals are subdivided into several similarly structured sections. Each of them reports the events of one year. In contrast to the annals of the Assyrian kings, the correlation to regnal years remains unclear.

Therefore, we can not exclude that some regnal years have been left out. However, the text's structure, in combination with a comparison with the stele inscription A 8-1 from Surp Sahak in Van, indicate that the sequence of the annual campaigns given in the report correlates with the actual sequence of events.

Descriptions of individual military actions are generally preceded by an introduction that gives a summary of the deeds achieved in one year and often include a prayer to the god Haldi and other deities. The accounts of successful campaigns that follow are portrayed as the answer to these prayers. A list specifying the precise number of men and animals taken as booty, and a closing formula are the final elements.

In most cases the number of men and animals is extremely high. It is therefore questionable whether these figures are trustworthy, although the specific quantities and the numerical proportion between various kinds of animals like sheep, oxen, horses, and camels make the data appear more reliable than the rounded numbers that can be found in Assyrian inscriptions.

The major routes of Argišti's military campaigns

According to both the Horhor annals and his military accounts, Argišti conducted a great number of campaigns in different regions, some of them far away from the Urartian capital Ṭušpa.

Overall, fifteen annual campaigns are recorded, which also provides us with the minimal duration of Argišti's reign.

During the first year reported in the Horhor Annals, Argišti conquered the territory of the population group Diauehi or, respectively, the people of the land Diaue/Diawe. This land is likely to be the land Daiaeni mentioned in inscriptions of the Assyrian kings Tiglath-Pileser I and Shalmaneser III. Since Shalmaneser III reported that he received the tribute of the king of the land Daiaeni after he had reached the source of the Euphrates in his 15th regnal year (Shalmaneser III 06 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/riao/Q004611] iii 34-45), Daiaeni was likely situated to the north of the modern Turkish city Erzurum.

Building activities

Agricultural infrastructure and irrigation systems

Several inscriptions report the construction of canals. Thus, A 8-2 (obv. 42') and A 8-3 (iv 73) report the construction of a canal from the Aras river in the land of ʾAza to service Argištiḫinili, whereas A 8-3 (v 17) reports the construction of a canal dug from the Dainalitini river. According to A 8-16 the area of Argištiḫinili was developed by the introduction of four canals as well as vineyards and orchards (ll. 8-9).

Fortresses

Of the fortresses built by Argišti I, Argištiḫinili (Armavir; A 8-22) and Erebuni (A 8-17 to 20) were the most important. Both included tower temples dedicated to the gods Haldi and Iubša. Further fortifications are mentioned in A 8-3 (iii 23-25).

Other buildings

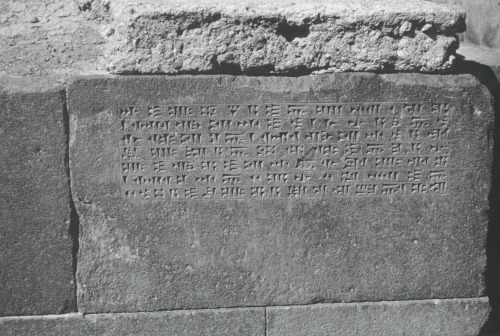

Argišti also reports the construction of other buildings and monuments, such as stelae (A 8-44 from Arinçkus), a šiname-building (A 8-43 from Aznarvurtepe), and a uḫini-building made of šua-stone (A 8-41 from Kalecik). He further describes the building of tower temples for the god Ḫaldi (A 8-22 from Armarvir/Argištiḫinili, most likely also A 8-23 as it is inscribed on a column base from Armarvir/Argištiḫinili, A 8-24 which is engraved on a cylindrical stone from Nalbandyan in the Armenian province of Armarvir, and A 8-39 from Davti-blur/Argištiḫinili) and for the god Iubša (A 8-21 from Arin-berd/Erebuni).

Remains of a tower temple from Arinberd with two inscriptions, photo: Mirjo Salvini CTU III: 234.

Stone block with an inscription (A 8-21) reporting the building of a tower temple from Arinberd, photo: Mirjo Salvini, CTU III: 234.

Inscriptions on metal objects

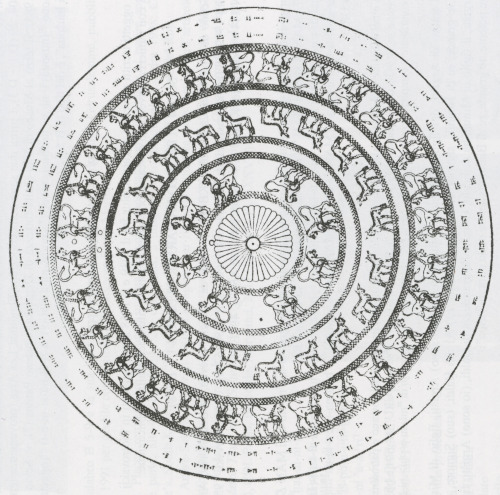

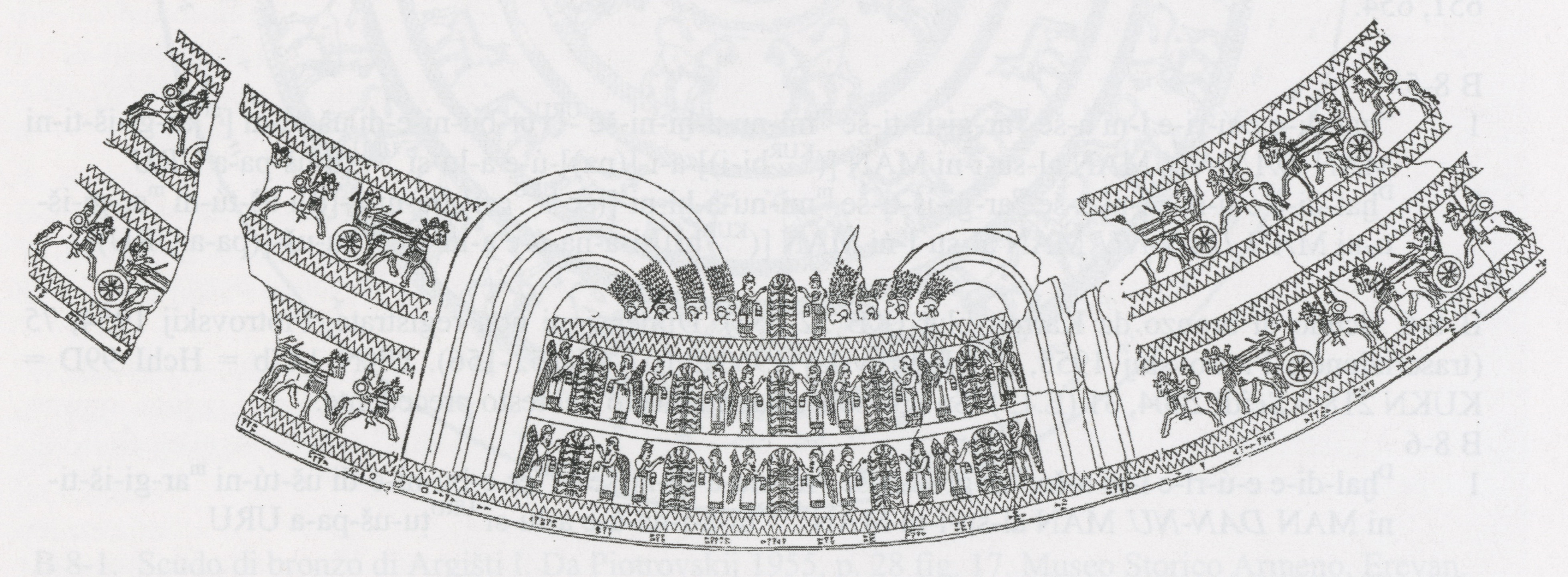

Bronze objects were found in Ališar/Verhram (A 8-22), Karmir Blur/Teišebani (B 8-1 to 21, 24-25, 28-29) and Van (B 8-26 to 27). The origins of B 8-27A are unknown. Some inscriptions explicity refer to Argišti as the owner of the object: B 8-19 to 20 (cups), B 8-22 (bell of a horse harness), B 8-23 to 24 (saddle girths of horse harnesses), B 8-25 (pads of horse harnesses), B 8-26 to 27 (parts of corselets), B 8-27A (a plate), and B 8-29 (belt buckle): Other inscriptions refer to votive offerings to Haldi. This group includes: B 8-1 to 9 (shields), B 8-10 to 13 (helmets), B 8-14 to 16 (quivers), B 8-17 (boutton/knob), B 8-18 (arrow head), B 8-21 (cylinder), and B 8-28 (a silver lid).

Bronze shield of Argišti I, sketch from Pjotrovskij (1955), photo: Mirjo Salvini, CTU IV: 34

Decoration of a helmet of Argišti I, photo: Mirjo Salvini, CTU IV: 36

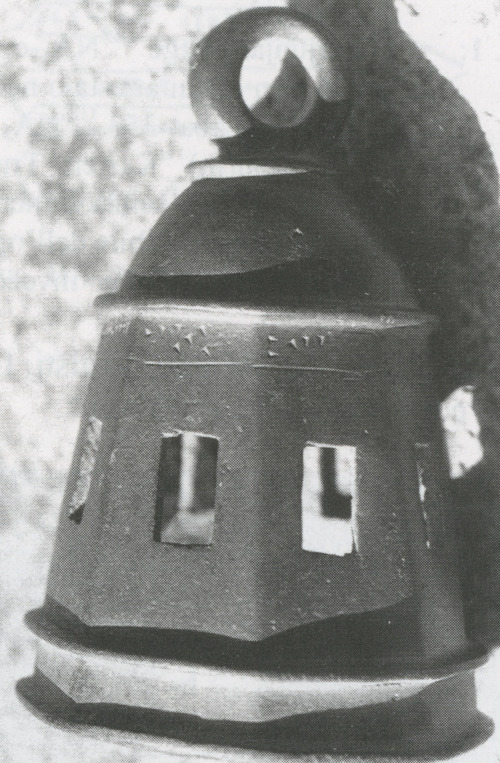

Bronze bell of Argišti I, photo: Mirjo Salvini, CTU IV: 40.

Food supply

Besides his military and building activities, Argišti I obviously took great efforts to ensure the full supply of grain. Records of the filling of silos in various places such as Erebuni or Argištiḫinili are given in several inscriptions (A 8-27 to A 8-35).

Further reading

Birgit Christiansen

Birgit Christiansen, 'Argišti I, son of Minua', Electronic Corpus of Urartian Texts (eCUT) Project, The eCUT Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2020 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/ecut/urartianrulersandtheirinscriptions/argitiisonofminuaa8andb8/]