Assurnasirpal's Northwest Palace

Early in his reign, king Assurnasirpal II commissioned a fabulous new palace, sited on the royal citadel TT on the east bank of the Tigris PGP river. The palace covered 28,000 m2, some 7 acres, and was designed around three or four courtyards. All the public areas were sumptuously decorated, to instill awe and wonder into palace visitors. The more private areas included a burial place for female members of the royal family. Formal and informal excavations since the 1840s have scattered finds from the palace all over the world.

Depicting Assyria's might

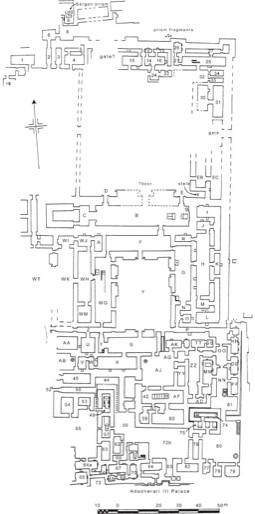

Image 1: Plan of Assurnasirpal's Northwest Palace in Kalhu, showing the room numbers mentioned in the text (1). View large image. Photo: BSAI/BISI.

All of the public spaces of the palace were sumptuously decorated, designed to impress and intimidate those privileged few who were allowed to enter. The walls were lined with bas-relief TT sculptures, brightly coloured, which sent messages of Assyria's glory. They focused on four themes in particular: the army's strength and prowess; the king's devout attention to the gods; the material prosperity; and the divine protection that flowed from those ways of behaving. Divine beings protected and blessed those that entered the palace, while warding off evil. Processions of dignitaries were shown, bringing tribute TT to the king. Scenes of warfare illustrated the dire consequences of not capitulating to Assyria's might. The king was depicted repeatedly making offerings and paying homage to the great god Aššur PGP and the deities of war.

Every one of the sculptured slabs was hewn by slave labour from nearby quarries, and dragged by rollers to the palace. There they were designed and carved by master craftsmen, who chose particular sets of images to fit the function of each room or suite. In this way, palace visitors and occupants were surrounded by messages about the king and his empire, which were suited to the context. For the benefit of those who could read cuneiform—but perhaps equally to impress those who could not—each panel was also overlain with a long inscription (the so-called Standard Inscription) extolling Assurnasirpal's ancestry, piety and military might, as well as a brief narrative of how the palace itself had been built.

Managing the palace

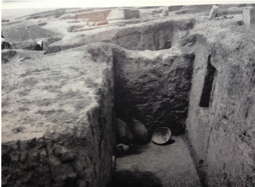

Image 2: Room ZT 13 of Assurnasirpal's Northwest Palace in Kalhu was used as a storage area in the late 7th century BC. This photo, taken during 1950s excavations by Max Mallowan's PGP team, shows the pottery that was found there as well as a wall cupboard. The thick walls supported an external tower but also helped insulate the room from cold and heat (2). View large image. Photo: BSAI/BISI.

The northernmost wing was the most public. It contained administrative offices and storerooms, workshops and the palace archives. The were probably two or three entrances: a ceremonial one to the east, a service entrance to the north which led to the administrative quarters of the god Nergal PGP 's temple, and perhaps another to the west with stairs down to the river. At the northeast corner there was a reception suite (Rooms 21, 25–26 and 32–34), which was perhaps the office of the rab ēkalli ("palace overseer") or another senior administrator. Two smaller suites of offices were situated immediately next door (Rooms 12-16, 22, 24; and 11, 15).

The oil and wine stores (Rooms 30-31) were also in this corner of the courtyard, where the administrators could keep an eye on them. One room contained enormous clay storage jars half-sunk into the ground for temperature control, and long benches on which smaller objects could be stacked (Image 2).

Further along the northern range was the tablet TT archive (Room 4, sometimes also referred to as ZT 4), where in the late 8th century BC scribes TT filed over three hundred letters to kings Tiglath-pileser III PGP and Sargon II PGP .

Encapsulating the empire

Image 3: Behind Assurnasirpal's throne was an imposing double image of the king, gesturing to the god Aššur. On either side of him winged genies TT fertilised the so-called sacred tree TT . The image was bigger than life size, at nearly 2 metres tall, and probably highly coloured. This carving is now in the British Museum (BM 124531) but other images from the throne room are now in Cambridge's Fitzwilliam Museum and many other collections worldwide (3). Read more about this object on the British Museum's website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Three monumental doorways in the south wall led from this outer court to the throne room. The walls between them were lined with low-relief sculptures of visiting dignitaries bringing gifts. The doorways themselves were flanked by monumental winged bulls TT . Uniquely, the bulls wore small fish-skin cloaks on their heads, a reminder of the seven sages TT who had lived in ancient times before the Flood TT , and brought knowledge to mankind. Their prominence here highlights the importance of scholarship and learning to Assurnasirpal's court.

The throne room itself was long and thin, running almost the whole width of the courtyard. Most people probably entered by the central doorway, where they saw an imposing double image of the king immediately opposite them, worshipping the god Aššur while two winged genies TT fertilised the so-called sacred tree TT (Image 3). They then had to turn to the left to see the king himself, seated on his throne on a dais in front of the narrow east wall. That wall too was decorated with a double image of the king and the Sacred Tree. When the audience was over, visitors would probably leave by the westernmost doorway to the outer courtyard, glimpsing yet another image of the king through the entrance to Room C to the west.

In between the focal royal images, the long walls of Assurnasirpal's throne room were lined with images of victorious sieges and battles, in two rows. The corners and doorways, meanwhile, were protected with full-height carvings of demons TT and genies to ward off evil spirits and attract the forces of good. Between the double registers of battle scenes, and across the middle of every full-size image of the king, sacred tree, and protective figure, was a cuneiform inscription. Although it was sometimes cut short to fit the space, this inscription is essentially always the same and is thus known now as the Standard Inscription of Assurnasirpal.

The king himself, and his immediate entourage, probably entered and exited the throne room from one of the doorways closest to the throne dais. The eastern doorway from the outer courtyard had a deep alcove set into it, where the famous Banquet Stela of Assurnasirpal was on show. On this large stone block was a long cuneiform inscription describing how Assurnasirpal rebuilt the city of Kalhu, including the palace and temples, and celebrated its completion with a gargantuan ten-day feast for nearly 70,000 people.

Receiving honoured guests

Image 4: Many of the low-relief sculptures from Assurnasirpal II's reception suites found their way to museums all over the world, while others still remain in situ on the site of Nimrud (4). This fine depiction of the king offering a libation TT in front of an attendant originally came from Room G in the Northwest Palace. It is now in the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, (A1956-132) where it has recently been conserved and redisplayed. Photo: © National Museums Scotland.

A single doorway in the southern wall of the throne room led into an anteroom (F) to a central courtyard (Y), where the king took his intimates and special visitors to one of three suites for more private engagements.

Three parallel rooms to the west were almost certainly the palace banqueting suite (Rooms WG, WH and WK, with Rooms A, WJ, WI and WM). Like the conference rooms in an expensive hotel, they had no fixed furniture but could be reconfigured and re-equipped to suit the occasion. Most importantly they looked down on the Tigris, giving guests a magnificent view of the busy river and surrounding countryside, plus the benefit of cool air. Like the throne room, this West Suite was decorated with double-register images of Assyrian military conquest, suggesting that the activities held here were very similar in tone and style.

At the opposite end of the central courtyard, the East Suite was very different in function (Rooms G-O and R). The highly repetitive large images on the walls of Rooms G and H show the king with his weapons and an offering bowl, surrounded by beneficent TT genies (Image 4). The floors, unusually, are both paved and drained. Here, then, the king came to pour liquid offerings to the gods and to receive their blessing and purification. He must have had human attendants with him to help conduct the ceremonies appropriately, although the bas-reliefs do not hint at their presence. The L-shaped inner rooms, I and L, were even more highly secured from divine and human intruders. Double-layered images of protective genies TT and sacred trees lined the walls to the foot of each L, where niches and a drain allowed the king to wash and relieve himself in full privacy, perhaps with guards standing sentry at each entrance. However, by the 8th century BC, these rooms had been relegated to storage areas.

The South Suite (Rooms S, T and X) links the central courtyard with the dense cluster of rooms to the south, where the large royal family lived. Its layout echoes that of the rooms around the throne room (Rooms B, F and C) but its decoration is much more like the highly protected East Suite. However, the innermost Room X is undecorated except for the Standard Inscription. Perhaps this room was hung with tapestries or carpets instead. This area must, then, have been the king's private residence suite, where he could relax a little with only his most intimate acquaintances, family members and staff to hand.

Behind the scenes: living with the dead

Image 5: This gorgeous crown comes from Tomb III in the Northwest Palace, and is hung with bunches of grapes made from lapis lazuli TT . Although it looks very delicate, it is in fact over 1kg in weight! It would be nice to think that the crown belonged to queen TT Mullissu-mukannišat-Ninua PGP , Assurnasirpal's wife. But in fact it was found on the body of a young woman whose head was much too small for it and we do not actually know for whom it was originally made (5).View large image. Photo: Iraq Museum.

The southern end of the palace contained the private living quarters of the royal family and their domestic staff. It was separated from the ceremonial northern half by Corridors P and Z, and presumably had at least one discreet exit to the outside world. Three underground chambers, accessed only from Room 74 via Room 75, may have served as the palace treasury. Water came from wells in Courtyards AB, AJ, NN and 80.

Amongst the complex web of interconnecting courtyards and corridors, rooms and suites two configurations stand out. First is the series of long rooms with cupboards and adjacent dead-end bathrooms around a kitchen (Room ZZ) containing benches, a bread oven and cooking vessels. Second is the altogether larger suite to the south of Courtyard AJ (Rooms 42 and 59–61), which may have belonged to Assurnasirpal's queen TT . These rooms were decorated with wall paintings rather than stone bas-reliefs, with human, floral and geometrical designs. But the queen's rooms also had ivory TT furniture with gold TT inlay.

This southern half of the palace did not only accommodate living occupants, however. Deep under the floors of Rooms MM, 49, 56 and 57 were four vaulted, brick-built tombs where prominent royal women were buried, along with their most precious belongings and jewels, over a period of about 150 years (Image 5). Inscriptions have identified some of the women as (in chronological order):

- Mullissu-mukannišat-Ninua PGP , wife of Assurnasirpal and mother of Shalmaneser III (Tomb III, under Room 57)

- Yabaʾ PGP , wife of Tiglath-pileser III PGP (Tomb II, under Room 49)

- Hamaya PGP , wife of Shalmaneser IV (Tomb III)

- Banitu PGP , wife of Shalmaneser V PGP (Tomb II)

- Ataliya PGP , wife of Sargon II PGP (Tomb II)

After Assurnasirpal

Image 6: We do know when or why so many beautiful objects were thrown down the wells of Assurnasirpal's palace, but it may have happened during the destruction of the palace in 612 BC. Perhaps looters tore the gold leaf off particularly fine furnishings and hurled the remnants away. This exquisite ivory panel, perhaps part of a throne, was made in Phoenicia PGP in the 9th or 8th century BC and presumably came to Kalhu as tribute or booty. Max Mallowan PGP 's team found it in the well of Room NN, along with many other precious things (6). The tiny bronze animal figurine now in Cambridge's Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology comes from the same findspot TT . Read more about this object (BM ME 127412) on the British Museum's website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Only king Assurnasirpal's son and immedidate successor, Shalmaneser III, continued to use the palace as it was originally intended. His own son Adad-nerari III PGP (r. 810-783 BC) built a new palace immediately to the south, while in the 8th century Tiglath-pileser III commissioned yet another residence in the centre of the citadel. When Sargon II's new city Dur-Šarruken PGP was completed in 710 BC, he moved out completely. Notably, the latest official correspondence and queens' burials also date to the end of the 8th century BC.

In the 670s BC king Esarhaddon PGP removed sculptures from the West Suite to re-use in his new residence elsewhere on the citadel. But even if the royal family no longer lived in the Northwest Palace, it continued to be used for offices and storerooms until the sack of Kalhu in 612 BC. At that point the invaders ripped through the building, ransacking its treasuries and throwing unwanted fragments of carved ivory furniture down the palace's many wells (Image 6). The building's last remaining guards also met that fate, if the manacled bodies discovered in the well of Courtyard 80 well are anything to go by.

Squatters occupied the ruins for a while, until the building fell into complete disrepair. Then, as described elsewhere, the Northwest Palace remained untouched and forgotten for around two and a half thousand years until rediscovered by Austen Henry Layard PGP in the 1840s. Subsequent excavations by teams of British, Polish, Italian and Iraqi archaeologists, as well as by more opportunist diggers, have scattered the palace's contents to the four quarters of the world. The process of reuniting them, online if not in real life, will be a project for many further decades to come.

Content last modified: 18 Dec 2019.

References

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB), pp. Figs. 15 and 33. (Find in text ^)

- Mallowan, M.E.L., 1966. Nimrud and Its Remains, vols. I-II, London: Collins, pp. 176, Fig. 108. (Find in text ^)

- Englund, K., 2003. Nimrud und seine Funde: Der Weg der Reliefs in die Museen und Sammlungen (Orient-Archäologie 12), Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf, pp. 43-58. (Find in text ^)

- Englund, K., 2003. Nimrud und seine Funde: Der Weg der Reliefs in die Museen und Sammlungen (Orient-Archäologie 12), Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf, pp. 79-138. (Find in text ^)

- Damerji, M., 2008. "An introduction to the Nimrud tombs", in J.E. Curtis, H. McCall, D. Collon and L. al-Gailani Werr (eds.), New Light on Nimrud: Proceedings of the Nimrud Conference 11th-13th March 2002, London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq, pp. 81-82 (free PDF from BISI, 22 MB), p. 82. (Find in text ^)

- Mallowan, M.E.L., 1966. Nimrud and Its Remains, vols. I-II, London: Collins, pp. I, 122-144. (Find in text ^)

Further reading

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB), pp. 36-70, 78-104.

- Roaf, M., 2008. "The décor of the throne room of the palace of Ashurnasirpal", in J.E. Curtis, J. McCall, D. Collon and L. al-Gailani Werr (eds.), New Light on Nimrud: Proceedings of the Nimrud Conference, 11th-13th March 2002, London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq in association with the British Museum, pp. 209-214 (free PDF from BISI, 22 MB).

- Russell, J.M., 1999. The Writing on the Wall: Studies in the Architectural Context of Late Assyrian Palace Inscriptions, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 9-63.

- Russell, J.M., 2008. "Thoughts on room function in the North-West Palace", in J.E. Curtis, J. McCall, D. Collon and L. al-Gailani Werr (eds.), New Light on Nimrud: Proceedings of the Nimrud Conference, 11th-13th March 2002, London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq in association with the British Museum, pp. 181-193 (free PDF from BISI, 22 MB).

Eleanor Robson

Eleanor Robson, 'Assurnasirpal's Northwest Palace', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thecity/northwestpalace/]