The ziggurat and its temples

Today, the archaeological site at Nimrud is dominated by the imposing pyramid-shaped remains of the city's ziggurat TT . This stepped tower was attached to the temple precinct which was located in the north-western part of the citadel TT , and must have been a spectacular centrepiece of Assurnasirpal II's magnificent new capital.

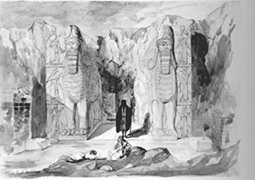

Image 1: Photograph of the side of the ziggurat at Nimrud taken in the 1970s or 80s, showing how it abutted onto monumental building works. Photo © Peggy and John Sanders. View large image on the website of the Oriental Institute, Chicago.

The nine shrines of Kalhu

Image 2: Drawing showing a proposed reconstruction of the temple complex and part of the Northwest Palace in the northwestern part of Kalhu's citadel TT (1). View large image. Photo: BSAI/BISI.

The inscriptions of Assurnasirpal II commemorate his activities in his new royal capital of Kalhu and record that the king built a total of nine temples in the city:

- the temple of the gods Ellil PGP and Ninurta;

- the temple of the god Ea-šarru PGP and goddess Damkina PGP ;

- the temple of the god Adad PGP and goddess Šala PGP ;

- the temple of the goddess Gula; PGP

- the temple of the god Sin PGP ;

- the temple of the god Nabu;

- the temple of the goddess Ištar Šarrat-niphi PGP ;

- the temple of the divine Sibitti PGP ;

- the temple of the divine Kidmuru PGP .

Significantly, the god Aššur is missing from this list because his only temple was in Assur PGP , the city with which he was closely identified. Of the nine shrines, four have been found during excavations in the 19th and 20th centuries: the temples of Nabu, Ninurta, Ištar Šarrat-niphi and Kidmuru. It is also possible that the structure known as the Central Building - located between the Governor's Palace and the Northwest Palace in the centre of the citadel TT - was in fact one of Assurnasirpal's nine temples. This proposed identification is based on the fact that stelae TT and statues were found in the building, a decorative feature which is very closely associated with temples. However, we do not know which deity may have been worshipped here. Work on the temple precinct, including the ziggurat, was continued by Assurnasirpal's son, Shalmaneser III, and Shalmaneser's successors in the 9th to 7th centuries BC.

The ziggurat and the temple of Ninurta

The ziggurat (derived from the Akkadian TT word zaqāru "to build high") was without a doubt the most spectacular sacred structure known from ancient Mesopotamia, where the earliest ziggurats date from the 3rd millennium BC. Their function is not precisely known, although it was presumably closely linked to the cultic functions of the associated temples. Herodotus PGP suggests in his Histories (Book I:181) that the ziggurat in Babylon was the scene of a "sacred marriage TT " between the god (in the guise of the king) and a priestess, a ritual TT which was designed to ensure continuing prosperity for the land. However, Herodotus's link between the sacred marriage and the ziggurat is not supported by other evidence from Babylonia or Assyria.

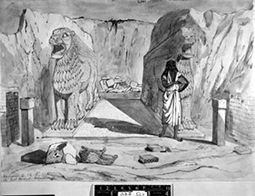

Image 3: A 19th-century watercolour by F. Cooper showing the façade of the Ninurta shrine, flanked by colossal human-headed lions and bas-reliefs TT of protective spirits (2). BM 2007,6024.155. View large image on British Museum website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The Kalhu ziggurat was constructed around a more or less square core measuring approximately 60 x 60 metres and made of unbaked mudbrick (Image 1). In the lowest part of the ziggurat, this was covered with stonework and decorative patterns of niches and half-columns, a feature commonly used in religious buildings. Above the stonework, the outside of the core was set back slightly and was faced using baked bricks inscribed with the name of Shalmaneser III, accompanied by a short inscription. This suggests that the ziggurat was built, or at least completed, during his reign. Bricks which appear to have been left over from the construction of the ziggurat were later also used for the pavements of the Governor's Palace. Inside the lowest level of the building was a large vaulted room measuring 30m long, 1.8m wide and 3.6m in height, whose exact function remains a mystery. Since no complete ziggurat has ever been found in Assyria, we can only speculate about what the upper parts of the Kalhu ziggurat may have looked like, or how the top was reached. Access in the lower parts of the structure may have been from within. However, George Smith PGP , who excavated the site in the 19th century, thought that he had seen the remains of an external staircase in the ziggurat's upper parts.

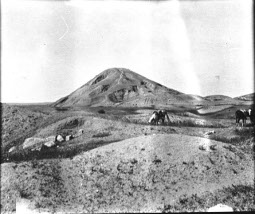

Image 4: The archaeologist and explorer Gertrude Bell visited the abandoned archaeological site of Nimrud in April 1909. She took this photograph of the ziggurat and several others, now in the Gertrude Bell Archive at Newcastle University. Image L_198, copyright Newcastle University. View this image on the Gertrude Bell Archive website.

According to bricks found at the site, the ziggurat was dedicated to Ninurta, a warlike god whose name may be the origin of the modern site-name Nimrud. Ninurta also had a large temple built for him by Assurnasirpal II, next to the site of the future ziggurat (Images 3 and 4). The temple itself consisted of a series of rooms which were elaborately decorated with colourful paintings showing figures and ornaments, and with inscribed reliefs TT and glazed TT bricks. Detailed inscriptions celebrating Assurnasirpal's achievements covered the walls, and a recessed area of the shrine held a huge alabaster TT slab (6.4 x 5m), which was likewise inscribed with the king's deeds on both the front and the back. The back of the slab would not have been visible to human visitors, but this was no obstacle for the gods who were able to read them all.

Assurnasirpal's inscriptions convey the splendour of the temple's interior, which - in common with the other temples of Kalhu - apparently displayed doors made of prized cedar TT wood and decorated with bronze TT bands, bronze images, and divine statues made of precious metals and stones, adorned with the loveliest spoils of war. The innermost shrine was decorated with gold TT and lapis lazuli TT as well as with gold dragons placed at Ninurta's throne (3). Unfortunately none of these magnificent decorations have survived. However, we can still appreciate the effect of the facade with its colossal lion figures (Image 3). Attached to the sacred part of the temple were extensive magazines TT used to store provisions for the temple. The sheer size and number of the pottery storage jars, which had a capacity of around 300 litres, is a clear indication of the temple's wealth and importance.

The temple of Šarrat-niphi

Image 5: Watercolour by F. Cooper showing the entrance to the Šarrat-niphi shrine flanked by two colossal lions, which were symbolic animals of the goddess Ištar (4). BM 2007,6024.149. View large image on British Museum website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Like the temple of Ninurta, the temple of Šarrat-niphi PGP was built by Assurnasirpal II, whose statue stood inside the temple. The temple celebrated the goddess Ištar PGP in her aspect as šarrat niphi ("blazing queen"). Entrance into the temple was protected by inscribed colossal lions, symbolic animals of the goddess Ištar (Image 5). The inscription was dedicated to Ištar and relates how Assurnasirpal built her temple using cedar beams for the temple roof and doors, and decorated it with beasts made of bronze and lions made of limestone and alabaster (5).

Like the temple of Ninurta, the surfaces of the Šarrat-niphi temple and its decorative elements contained lengthy inscriptions commemorating Assurnasirpal's deeds and piety. The length and number of inscriptions recorded here are without precedent, and represent a major innovation of Assyrian monumental architecture. It has been suggested that Assurnasirpal was inspired during his visit to Lebanon PGP , where he may have come into contact with the Egyptian practice of using extensive text and imagery as part of royal self-expression.

The temple of the Kidmuru

The temple of the Kidmuru PGP - or, more accurately, of Ištar, mistress of the Kidmuru - is the only shrine which is known to have predated Assurnasirpal's rebuilding of Kalhu. An inscription of the king describes the run-down state in which he found the ancient shrine:

The temple of the goddess Ištar, mistress of the divine Kidmuru, which had previously existed (but already) in the time of the kings my fathers had crumbled and turned into ruin hills... I rebuilt for her this temple of the divine Kidmuru. (6)

Like other Mesopotamian buildings, it was built primarily with unbaked mudbrick, but baked (and therefore more durable) bricks were used for the flooring of the courtyard. To commemorate the temple's completion, alabaster foundation documents were deposited inside the building's walls. The shrine was decorated using glazed pegs and tiles which were placed along the walls, while oil and incense TT burners provided light and perfumed the air. An image of the goddess made out of red gold occupied a central position within the shrine. This striking-looking statue was placed on top of, or behind, a platform decorated with the feet of a lion, an animal which was symbolically linked with the goddess (see also Image 5).

Ištar was not the only occupant of the Kidmuru shrine. The northern facade of the shrine housed three pedestals, each dedicated to a separate deity. The inscription on one of these pedestals shows that it belonged to Ellil PGP "resident in the temple of the Kidmuru" (Image 6). The other two occupants were most likely Šamaš PGP (who is listed elsewhere as a witness to a loan made by the goddess) and the Assyrian national god, Aššur. An inscribed brick TT from the Northwest Palace provides evidence that the temple had its own well, although it has not been found or excavated. We cannot exclude the possibility that objects from the temple were thrown into the well when the city was sacked at the end of the 7th century BC, as was the case with the wells elsewhere in the city.

There is evidence that the temple continued to be used into the 7th century. For instance, in a petition to king Assurbanipal PGP , Urad-Gula PGP , a court scholar TT down on his luck, enumerates his misfortunes, saying among other things, "I have visited the Kidmuru temple and arranged a banquet, (yet) my wife has embarrassed me; for five years (she has been) neither dead nor alive, and I have no son" (SAA 10: 294). It seems likely that the temple to which Urad-Gula paid a visit was the Kalhu temple of Ištar, mistress of the Kidmuru and that he did so in order to implore the goddess - apparently unsuccessfully - to cure his wife's infertility.

Content last modified: 18 Dec 2019.

References

- Reade, J.E., 2002. "The ziggurrat and temples of Nimrud", Iraq 64, pp. 135-216 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. 137, Fig. 2. (Find in text ^)

- Reade, J.E., 2002. "The ziggurrat and temples of Nimrud", Iraq 64, pp. 135-216 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. 169, Fig. 31. (Find in text ^)

- Grayson, A.K., 1991. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC: I (1114-859 BC) (Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Periods. Volume 2), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 291, A.0.101.30:61-73. (Find in text ^)

- Reade, J.E., 2002. "The ziggurrat and temples of Nimrud", Iraq 64, pp. 135-216 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. 183, Fig. 41. (Find in text ^)

- Grayson, A.K., 1991. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC: I (1114-859 BC) (Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Periods. Volume 2), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 283-286, A.0.101.28. (Find in text ^)

- Grayson, A.K., 1991. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC: I (1114-859 BC) (Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Periods. Volume 2), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 304, A.0.101.38:19-25. (Find in text ^)

- Reade, J.E., 2002. "The ziggurrat and temples of Nimrud", Iraq 64, pp. 135-216 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. 146, Fig. 8. (Find in text ^)

Further reading

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB).

- Postgate, J.N. and J.E. Reade, 1976-1980. "Kalhu", Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 5, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 303-323.

- Reade, J.E., 2002. "The ziggurrat and temples of Nimrud", Iraq 64, pp. 135-216 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers).

Silvie Zamazalová

Silvie Zamazalová, 'The ziggurat and its temples', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thecity/zigguratandtemples/]