Adad-nārārī I

Quick links

Introduction

The inscriptions

Building

projects

Index of geographic, ethnic, and tribal names in the

inscriptions of Adad-nārārī I

Text no. 41

Adad-nārāri I (1305-1274 BC) was, according to the Assyrian King List [/riao/kinglists/assyriankinglist/assyriankinglist/index.html#MiddleAss], the seventy-sixth ruler of Aššur. He was the fourth, after Aššur-uballiṭ [/riao/thekingdomofassyria13631115bc/ashuruballiti/index.html], (presumably) Enlil-nārāri [/riao/thekingdomofassyria13631115bc/enlilnarari/index.html], and Arik-dīn-ili [/riao/thekingdomofassyria13631115bc/arikdinili/index.html], to adopt the title "king of Assyria" (šar māt Aššur). His was also the first reign during which extensive narratives recounting military events were recorded in the royal inscriptions. Adad-nārāri was the son and successor of Arik-dīn-ili and the father and predecessor of Shalmaneser [/riao/thekingdomofassyria13631115bc/shalmaneser/index.html] I. His name appears in several later inscriptions detailing his involvement in different building projects at Aššur: Shalmaneser I text no. 6 [/riao/Q005794/]: 15 (Ištar Temple), Tukultī-Ninurta I text no. 14 [/riao/Q005850/]: 13 (Dimitu Temple), Tiglath-pileser I text no. 1011 [/riao/Q005966/]: 3' (Anu Adad Temple?), Aššur-bēl-kala text no. 7 [/riao/Q005988/] v 25 (facing of the great tower of the Tigris Gate), Adad-nārāri II text no. 1 [/riao/Q006020/] r. 11' (facing of the quay wall at the entrance of the city), Shalmaneser III text no. 10 [/riao/Q004615/] iv 43 (wall of the New City).

Following the reigns of Aššur-uballiṭ and his two successors, Adad-nārāri I inherited an ascending regional power within an unstable political situation. It was first necessary for the king to defend Assyria from the pressure exerted by the mountain dwellers to the north and north-east, while at the same time attempting to extend the frontier with Babylonia, below the Lower Zab. However, he also had the opportunity to expand westwards and take advantage of the disintegration of the Mittanian kingdom. Adad-nārāri did not put an end to Assyria's problem with the mountain dwellers, although he continued to lead defensive campaigns, like his predecessors. On the southern front he succeeded in defeating the Kassite king Nazi-Muruttaš and, according to the Synchronistic History (Grayson, TCS p. 161 i 28'-31'), concluded an official agreement with him to establish a new border between the two countries, which extended his control from the Lower Zab towards the region of the Diyala.

On the western front, Adad-nārāri led the conquest of Mittani in two stages: the campaign against Šattuara I, who submitted to becoming a vassal of Assyria; and the campaign against his rebellious son Usašatta, which resulted in the conquest of the territory between Baliḫ and Ḫābūr, and further west as far as the Hittite vicergal kingdom of Carchemish, on the banks of the Euphrates. It is possibly because of these military achievements, which granted him control over Upper Mesopotamia, that Adad-nārāri began to use the title "king of totality, of the universe" (šar kiššati) for the first time since the reign of Samsī-Addu I [/riao/fromsamsiaddutomittanicilent18081364bc/samsiaddudynasty/samsiaddui/index.html#Inscriptions], who introduced the title in Assyria, after an equally remarkable military achievment.

The success of his numerous conquests solidified Adad-nārāri I's position among the great powers of the second millennium. As Aššur-uballiṭ had been able to start diplomatic relations with Egypt and Babylonia, Adad-nārāri approached the king of Ḫatti from an advantaged position, given the new territorial context following the conquest of Mittani/Ḫanigalbat. Still, his preference was to engage in a peaceful relationhip with his "brother" Urhi-Tessub (Mursili III). However, the Hittite king, having lost his authority over the former Mittanian region east of the Euphrates to Adad-nārāri, did not appear in any way ready to come to good terms with the Assyrian king, who he also refused (on the basis of former customs) to call "my brother," although he did acknowledge Adad-nārāri's position as "Great King."

The following draft of a letter from Urhi-Tessub to Adad-nārāri I is the answer, in the aftermath of the victory against Usašatta, to the Assyrian proposal to establish brotherly relations and to allow the Assyrians free passage to Mount Amanus (in modern Lebanon), possibly to gather the precious timber or even to erect a stele:

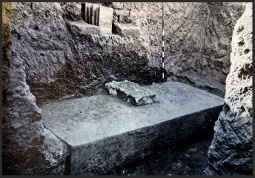

Photo from Walter Andrae's excavations at the Assyrian Ištar temple in Aššur (Andrae 1977, p. 160 Abb. 140). Neatly set in a niche standing upright in the centre of the back wall of the cella of the temple, five stone slabs with Adad-nārāri's building inscriptions recording his work on the temple are visible. They are ex. 1-5 of text no. 15 [/riao/thekingdomofassyria13631115bc/adadnararii/texts119/index.html#adadnarari115]. Below them the very large stone block inscribed with Tukultī-Ninurta I's text no. 11 [/riao/thekingdomofassyria13631115bc/tukultininurtai/texts119/index.html#tukultininurta111] (ex. 1; 268 x 130 x 40 cm and 350 kg; ex. 9 lead tablet, 75 x 38 cm) lies on the floor. Tukultī-Ninurta was Adad-nārāri's grandson; he completed the restoration of the temple and positioned the foundation inscriptions as were then discovered by German archaeologists.

Hattusili, Urhi-Tessub's successor, used a very different approach to the Assyrian king and immediately ceased any form of hostility towards him, offering (as he did with all the other Great Kings) to establish their relationship as peers. Now it was Hattusili who sought the favour of the neighboring kings, including the king of Assyria, to strengthen his fragile political position. And now it was Adad-nārāri, an established great king and "brother," who was unwilling to grant diplomatic recognition of Hattusili's status.

The inscriptions

Like the reigns of Samsī-Addu I before him and Tiglath-pileser I after him, Adad-nārāri I's reign is remarkable in the history of royal inscriptions. As mentioned earlier, it was at this time that inscriptions began to include large portions of text dedicated to the narration of military events. If text no. 1 [/riao/pager/Q005738/] offers geographical summaries of military successes, text no. 3 [/riao/pager/Q005740/] is especially dedicated to the victory over Ḫanigalbat, and exhibits the narrative dynamism that will distinguish Assyrian annalistic inscriptions in the future: not only the name of the captured cities are included, but a comprehensive description of the events starting with the rebellion and taming of king Šattura, and continuing with the revolt of his son Uasašatta, his unsuccessful petition for help from the Hittites, his defeat, and finally Adad-nārāri's conquest, destruction, and pillage of the major cities of the kingdom.

Text no. 07

A further development in the production of royal inscriptions was quantitative. The scribes working in the king's entourage were required to prepare a great number of inscriptions for each building project carried out by the ruler. For the composition of these texts they often adopted a system of standardized introductions and conclusions which were used to open and close – more or less always in the same way – the central body of an inscription. For this reason, Assyriologist have, since E. F. Weidner's edition (1926), grouped three standard models of introductions and conclusions in the first three texts [/riao/Q005738,Q005740,Q005740/] of this king, editing only the central body of those inscriptions, whose opening and/or closing corresponded to one of them.

Building projects

Apart from a building project at Taidu, the conquered royal city of Ḫanigalbat (texts nos. 4-5, and 22), Adad-nārāri's building activities almost all took place at Aššur. Major works were undertaken at the temple of the Assyrian Ištar (nos. 6, 15, 18, and 37?), at the Aššur temple (nos. 19, 31, 35-36, and 42), at the ziqqurrat (nos. 21 and 24), at the palace (nos. 16, 29-30, and 38), at the quay walls on the east side (nos. 8-9 and 40), north side (nos. 11, 13, and 39), and at unidentified sites (no. 12). The city walls of the Inner City (no. 14) and of the New City (no. 10) were also restored, as well as the Step Gate (no. 7), the Adad-Anu Gate (no. 17), and some other unknown structures (nos. 33-34).

Index of geographic, ethnic, and tribal names in the inscriptions of Adad-nārāri I

In text no. 01 [/riao/Q005738/], Adad-nārāri I provides two summaries of his conquests. In the first (and shorter) account, he defines himself as the conqueror of the armies of the Babylonians (Kassites) on the south, the Gutians and Lullumus from the eastern and north-eastern mountainous regions of the Zagros, and of the Šubarus in upper Mesopotamia. The ruler also defined the scale of these military undertakings by remembering that each of his predecessors (for whom we often lack military accounts) had to fight, among others, one of the same enemies: Arik-dīn-ili with the Gutians, Enlil-nārāri with the Kassites, and Aššur-uballiṭ with the extensive land of Šubaru. The four of them were entitled to the epithet "extender of the border and boundaries" (murappiš miṣri u kudurri), and some of the toponyms listed below are of conquests attributed to them, including the Hurrian Turukku and Nigimhu (see his text no. 8: 13'), Kutmuḫu and its allies Aḫlamu-Arameans, Sutu, and Iūru to Arik-dīn-ili [/riao/thekingdomofassyria13631115bc/arikdinili/index.html], and the land of Muṣru to Aššur-uballiṭ [/riao/thekingdomofassyria13631115bc/ashuruballiti/index.html].

In the second and longer summary of his conquests, Adad-nārāri included a list of toponyms, ordered geographically. He 'scatters' the enemies above and below and 'tramples' on their lands from Lubda, in the east Tigris region (near Arrapḫa), to Rapiqu, on the mid-lower Euphrates (and on the border with Suhu), and then up to Eluḫat at the northern edge of the Kašiyari mountains. He conquered Taidu, Šuru, Kaḫat, Amasaku, Ḫurra, and Šuduḫu, which formed an arch in the area of the Ḫarmiš, the eastern reach of the Ḫābūr, and then further west to Nabula, Waššukanu, Irridu, again Eluḫat, the fortresses of Sudu and Ḫarranu, finally reaching Gargamiš on the Euphrates. Lastly, a further record of Adad-nārāri's campaign against Babylonia can be found in the fragmentary text no. 21 [/riao/pager/Q005758/] which describes his siege of the Kassite king Nazi-Muruttaš in the city Kar-Ištar.

Names are ordered according to geographical area (see key-map)

| Name | Determinative* | Type | Modern Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assyrian Triangle | ||||

| Aššur | 0, DINGIR | city | Qal'at Shirqat | Text no. 3: 10, 14, 33, 49; 16: 33 (DINGIR) |

| Canal of the Palace Complex | 0 | infrastructure | Qal'at Shirqat | Text no. 39: 4–5 |

| Inner City (Aššur) | URU, 0 | district of Aššur | Qal'at Shirqat | Text no. 11: 5'; 13: 30 (0); 14: 4 |

| Lower City (Aššur) | 0 | district of Aššur | Qal'at Shirqat | Text no. 8: 25 |

| New City (Aššur) | 0 | district of Aššur | Qal'at Shirqat | Text no. 10: 35; 13: 29, 30 |

| Tisaru (Aššur) | 0 | district of Aššur | Qal'at Shirqat | Text no. 10: 36 |

| Upper City (Aššur) | o | district of Aššur | Qal'at Shirqat | Text no. 10: 36 |

| Tigris (understood) | ÍD | river | Text no. 8: 24; 9: 5; 10: 35 | |

| Babylonia and Mid Euphrates | ||||

| Karduniaš (Babylonia) | KUR | land | Babylonia | Text no. 21: 11' |

| Kassites | 0 | people | Babylonia | Text no. 1: 3, 25 |

| Rapiqu | KUR | city | Mid Euphrates | Text no. 1: 7 |

| Ḫanigalbat (Mittani), north. Balīḫ, north. Ḫābūr, south. Turkey, | ||||

| Amasaku | URU | city | Text no. 1: 9; 3 27 | |

| Carchemish | URU | city | Ğarablūs, krkymyš | Text no. 1: 13 |

| Euphrates (Upper) | ÍD | river | Text no. 1: 14; 3: 41 | |

| Ḫanigalbat | KUR | land | Text no. 3: 5 | |

| Ḫarran | 0, URU | city | Ḥarran, Carrhae | Text no. 1: 13;,3: 40 (URU) |

| Ḫatti | KUR | land | Text no. 3: 18 | |

| Hittite(s) | 0 | people | Text no. 3: 19 | |

| Ḫurra | URU | city | Text no. 1: 10; 3: 29 | |

| Irridu | URU | city | Text no. 1: 11; 3 :35, 37, 47, 49, 50; 26: 4 (ex. 13) | |

| Kaḫat | URU | city | Text no. 1: 9; 3: 28 | |

| Naḫur | URU | city | Text no. 25: 4' | |

| Šuduḫu | URU | city | Šāġir-Bāzār | Text no. 1: 10; 3: 29 |

| Taidu (Taʾidu) | URU | royal city | Tall al-Ḥamīdīya | Text no. 1: 8; 3: 26, 37; 4: 39 |

| Waššukanu | URU | city | Tell Faḫārīya | Text no. 1: 11; 3: 30 |

| Area of and around the Kašiyari range, upper Mesopotamia, and north. Tigris | ||||

| Aḫlamû(-Aramaeans) | 0 | people | Text no. 1: 23 | |

| Eluḫat | 0, URU | city | Text no. 1: 8, 12; 3: 38 (URU) | |

| Iūru | 0 | people | Text no. 1: 23 | |

| Kašiyari | 0, KUR | mountain range | Ṭūr ʿAbdīn | Text no. 1: 12; 3: 38 (0) |

| Nabulu (Nabula) | URU | city | Gir Nawas, Girnavaz | Text no. 1: 10; 3: 28 |

| Sūdu | URU | city | Text no. 1: 13; 3: 40 | |

| Sutû | 0 | people | Text no. 1: 23 | |

| Šubaru | 0, KUR | land, people | Text no. 1: 4, 32 (KUR) | |

| Šuru | URU | city | Sauras, Tzauras | Text no. 1: 9; 3: 28 |

| Kutmuḫu (Katmuḫu) | KUR | land | Text no. 1: 22 | |

| Muṣru | KUR | land | Text no. 1: 31 | |

| mid-, mid-eastern Tigris | ||||

| Lubdu (see Lubda) | 0 | city | Tawūq, Daduq | Text no. 1: 7 |

| Ubasē | URU | city | Tell Ḥuwaiš | Text no. 7: 42; 8: 30 |

| north. and eastern Zagros | ||||

| Lullumu (Lullubu) | 0, KUR | people | Text no. 1: 4; 1001: 12' (KUR) | |

| Nigimḫu (Nigimḫi) | KUR | land | Text no. 1: 20 | |

| Qutu (Gutians) | 0 | people | Text no. 1: 4, 21 | |

| Turukku | KUR | people | Text no. 1: 19 | |

| Unknown | ||||

| Ša-ama... | URU | city | Text no. 43: 4 | |

| * 0 = no det.; [...] = erased | ||||

Bibliography

Browse the RIAo Corpus [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/riao/pager/]

Nathan Morello

Nathan Morello, 'Adad-nārārī I', The Royal Inscriptions of Assyria online (RIAo) Project, The RIAo Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2022 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/riao/thekingdomofassyria13631115bc/adadnararii/]