Building Activities

Just like other rulers of Mesopotamia, Sargon II carried out numerous building projects throughout his realm, in particular in Assyria and Babylonia, and especially at his new capital city Dūr-Šarrukīn.[130]

Khorsabad (Dūr-Šarrukīn)

The founding and construction of Dūr-Šarrukīn ("Wall of Sargon" or "Fortress of Sargon") to be the new royal center of Assyria is the most important building activity carried out during the reign of Sargon and is recorded in a large number of his royal inscriptions. Most of these texts come from Khorsabad (see in particular text nos. 2, 7–9, 11–14, 41, 43–48, and 51–56), but a number come from other cities, in particular from Nineveh (see text nos. 84–85) and Arslantepe (ancient Melid; text no. 111). Moreover, bricks stating that they were from the palace of Sargon or mentioning the building of the city Dūr-Šarrukīn and its palace have been found at numerous locations outside of the city itself: Nimrud, Nineveh, Karamles, Tag, Tepe Gawra and possibly Djigan (see text nos. 50 and 53).

Sargon states that he founded the new city in order to make the land of Assyria prosper and that rather than expropriate land for the city he purchased it from its previous owners, paying them either in silver and bronze according to the original purchase prices for the land or with equivalent land elsewhere.[131] The new city was located about fifteen km upstream from Nineveh, at the site of a town called Maganuba and "at the foot of Mount Muṣri." Archaeological work has shown that the new city was approximately square in shape (1800×1700m) and covered an area of about 300 hectares. The Assyrian Eponym Chronicle (see below) states that the city was founded in 717 and Assyrian inscriptions tell us that individuals captured during Sargon's various campaigns were used as laborers on the massive building project. [132] According to the Assyrian Eponym Chronicle, various gods entered their temples in the city on the twenty-second day of Tašrītu (VII) in 707 and the city was inaugurated on the sixth day of Ayyāru (II) in 706.[133] Thus, the construction of the city had taken about ten years and been concluded only about a year before the king's death. To celebrate the completion of the city and palace, Aššur and the other deities of Assyria (presumably their statues) were invited to the city, where the king made sumptuous offerings to them.[134] After the deities returned to their own cities, the king took up residence in his palace and held a great festival, one to which numerous foreign rulers, officials, nobles, and important Assyrians were invited. These 'guests' presented to the king substantial tribute, including among other things precious metals, garments, aromatics, ivory, ebony, horses, and oxen.[135] Among the people settled in the new city were the foreign captives who had been employed in building it, along with their Assyrian overseers and commanders.[136]

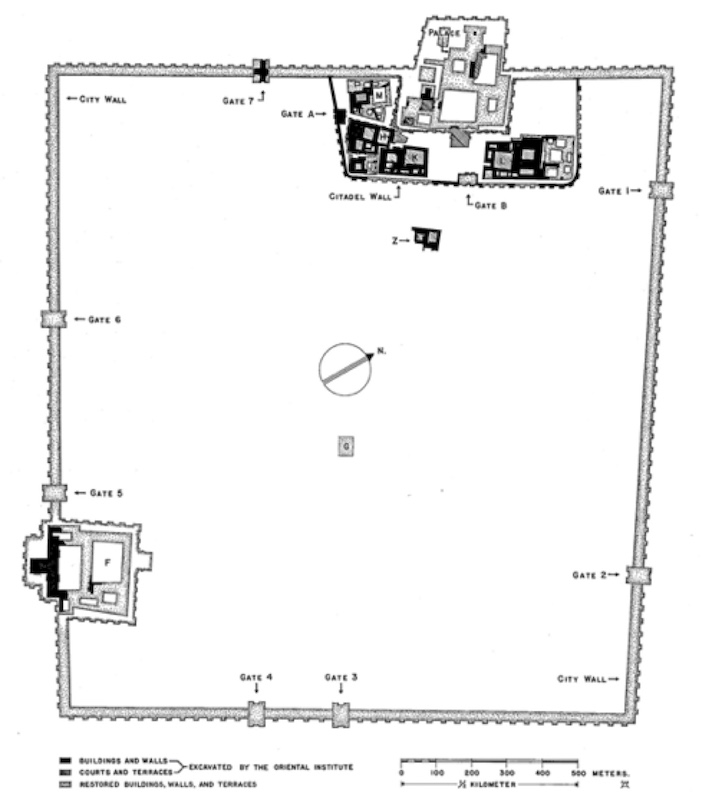

In preparation for commencing work on the city, bricks were made at an auspicious time, in the month Ṣitaš/Simānu (III), and the foundations of the city were laid in the month Abu (V).[137] The texts record in particular work on the city wall, with its gates, and the palace, with its chapels to the deities Ea, Sîn, Ningal, Adad, Šamaš, and Ninurta. The city wall is said to be 16,280 cubits long and to comprise two separate walls, an outer wall with a name honoring the state god Aššur ("The God Aššur Is the One Who Prolongs the Reign of Its Royal Builder (and) Protects His Troops [var.: Offspring]") and an inner wall with one honoring the warrior god Ninurta ("The God Ninurta Is the One Who Establishes the Foundation of His City [var.: the Wall] for (All) Days to Come"). Three texts state that there were eight gates in the city wall: two gates in each of the four sides of the city and each gate having a name honoring one of the gods. The published plan of the city (see Figure 3) has only one gate in its north(west) side. However, J.E. Reade has noted that at the point where the royal palace platform projects from the citadel, the line of the city wall was clearly eroded and the published ground plans are partly hypothetical. He thus suggests that there may have been a postern gate below the ziggurrat on the palace platform, just as there was one below the South-West Palace of Sennacherib at Nineveh. Since the gates are listed in a counterclockwise order (east > north > west > south), the presumed postern gate would have been the one called "The God Enlil is the One Who Establishes the Foundation of My City."[138]

Figure 3. Plan of the city of Khorsabad. Reprinted from Loud and Altman, Khorsabad 2 pl. 69 courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

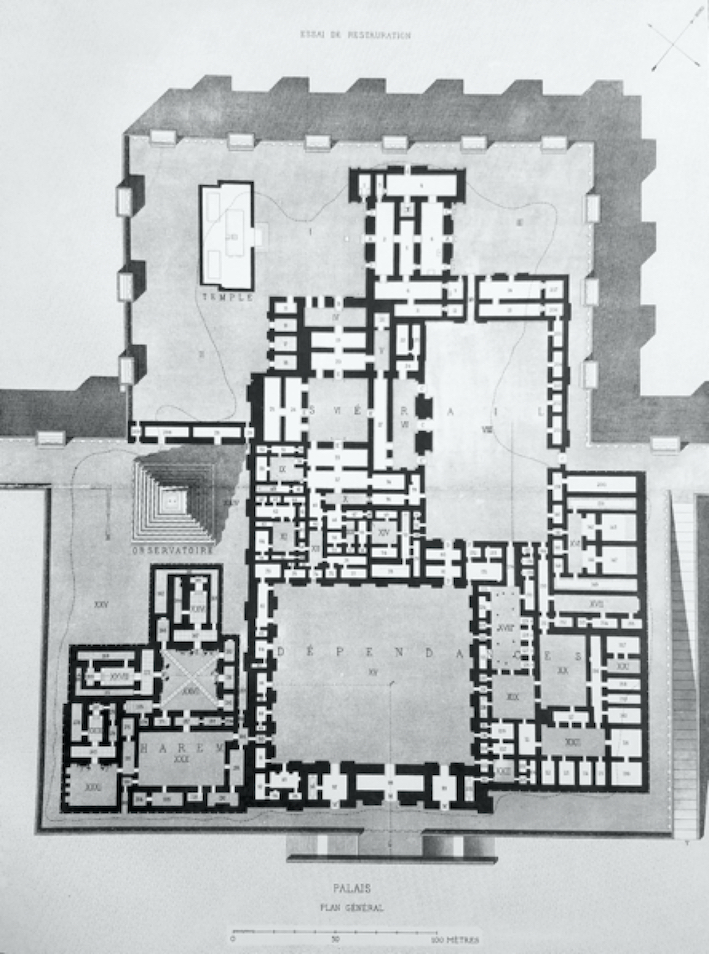

Figure 4. Plan of the palace at Khorsabad, as restored by V. Place. Reprinted from Loud and Altman, Khorsabad 2 pl. 76 courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

The palace complex (see Figure 4) and the adjoining temple of Nabû were located on raised platforms connected by a bridge within the city's 'citadel' located against the northwestern city wall; the palace partially protruded beyond the regular plan of the city wall. The palace complex consisted of over two hundred rooms and courtyards, as well as a ziggurrat. The palace was given the name égalgabarinutukua, "Palace That Has No Equal," and all types of luxurious materials were used in its construction. In one part of the palace was a bīt ḫilāni structure in imitation of a Hittite palace.[139] Pavement inscriptions have been found identifying the chapels of Ninšiku (Ea), Sîn, Ningal, Adad, Šamaš, and Ninurta within the palace complex (text nos. 16–21),[140] as well as the temple of Nabû (text no. 22).

Although the temple of Nabû was the largest religious structure at the city, no inscriptions appear to record its construction apart from a brief mention on inscribed stone slabs used as thresholds or on or near steps in the temple itself (text no. 22). The Khorsabad Cylinder inscription (text no. 43 line 43) states that Sargon ordered that a simakku-shrine of Šamaš be constructed in the city, but nothing further is known about it. Brick inscriptions (text nos. 54–55) record the construction of the temple of Sîn and Šamaš in the city, but it is not clear if this refers to the chapels of these gods within the palace complex, the simakku-shrine, or some other independent temple (or temples).[141] Archaeologists discovered a temple in the lower city in which there were numerous stone altars. The inscription on the altars only refers to them being set up for the Sebetti by Sargon, and not to the construction of the temple itself (text no. 49). No inscription refers to the ziggurrat constructed behind the palace chapels on the palace terrace.

Within the citadel were located at least four large residences (J, K, L, and M), the largest of which being the residence of the king's brother and grand vizier Sîn-aḫu-uṣur. Three pavement slabs from Sîn-aḫu-uṣur's residence (L) state that he had constructed the building (text no. 2002). In the lower city, adjacent to the southern city wall was located the city's ekal māšarti (Palace F), but no royal inscription mentions its construction,[142] although several inscriptions of Sargon were found there.[143] Around the city Sargon had a botanical garden (or great park, kirimaḫḫu) created, one that was to be a replica of Mount Amanus and to have every kind of aromatic plant and fruit-bearing mountain tree.[144]

Aššur

At the city of Aššur, work was carried out on Eḫursaggalkurkurra, the main cella within the temple of the god Aššur, in particular on the processional way in the temple courtyard (text nos. 69–70) and on a glazed brick frieze from the temple (text no. 71), but also on the towers (text no. 67). A cylinder inscription from Nineveh refers to "shining zaḫalû-silver for the work on Eḫursaggalkurkurra ("House, the Great Mountain of the Lands"), the sanctuary of the god Aššur [...] ... the goddesses Queen-of-Nineveh and Lady-of-Arbela."[145] In addition, one letter from the governor of the city (Parpola, SAA 1 no. 77 [=Harper, ABL no. 91]) describes work on the palace of the inner city. Work may also have been carried out on the temple of the gods Sîn and Šamaš.[146]

Kalḫu

Sargon had the Juniper Palace at Kalḫu (modern Nimrud), which had previously been built by Ashurnasirpal (II), completely renovated, from its foundations to its crenellations. Upon its completion, he invited Nergal, Adad, and the other gods dwelling in the city, to come inside and he then held a festival. Silver and gold that had been taken as booty from Pisīris, king of Carchemish, were stored there (text no. 73). Very little of the end of the Nimrud Prism inscription (text no. 74) is preserved and what little there is refers to work at Dūr-Šarrukīn, but it is not impossible that some work at Kalḫu had also been mentioned.

Nineveh

Two bricks from the temple of Nabû at Nineveh record that Sargon completely (re)built that temple (text no. 96 and cf. text nos. 93 and 97), while several other bricks, pavement slabs, and cones found at Nineveh state that the king had completely (re)built the temple of the gods Nabû and Marduk (text nos. 92 and 95). The inscription on the cones states that Adad-nārārī III (810–783) had previously restored the temple.[147] Inscribed copper coverings for doorjambs in the temple of Nabû have also been recovered (text no. 99).[148] Although the passage is damaged, the Nineveh Prism likely indicates that Sargon had carried out work on a ziggurrat, possibly the one of Adad at Nineveh (text no. 82 viii 4´´´b–8´´´).

One inscribed wall slab of Sargon's is said to have been found at Nebi Yunus, the secondary mound (likely the ekal māšarti) at Nineveh (text no. 81), but it is not impossible that it was actually brought there by one of Sargon's successors or in modern times.[149] In addition, a later inscription of Ashurbanipal (Novotny and Jeffers, RINAP 5/1 p. 220 no. 10 v 33–42) states that Sargon had been the builder of the akītu-house of the goddess Ištar that was inside Nineveh.

Ḫarrān

A broken passage in a cylinder inscription from Nineveh (text no. 84 line 6´) refers to "seven and a half minas of shining silver for the work of Eḫulḫul ("House which Gives Joy"), the abode of the god Sîn who dwells in the city Ḫarrān." This presumably refers to some construction work on the temple or on some item associated with it.

Dēr

According to one letter (Fuchs and Parpola, SAA 15 no. 113 [=CT 54 no. 89+]), work was carried out on the fort and outer city wall at Dēr.

Tabal

The Khorsabad Annals (text no. 1 lines 202b–204a; cf. text no. 2 lines 234b–235a) may refer to some construction in the land Tabal, and in particular the construction of an enclosure wall (kerḫu), in connection with the settlement of people there and the appointment of one of Sargon's eunuchs as governor over them. As noted by Fuchs,[150] it is possible that this work was never completed.

Til-Barsip

A poorly preserved inscription from Til-Barsip (modern Tell Ahmar), possibly on part of a bull colossus (text no. 107), appears to refer to a temple of Adad, possibly one that Ashurnasirpal (II) had originally constructed, but it is not clear in which city that structure was located.

Carchemish

A brief brick inscription (text no. 110) that refers to the palace of Sargon has been discovered at Carchemish and a nearby site (Tell Amarna), and this could suggest that there was a royal palace there. Three copies of a clay cylinder inscription of the king found at Carchemish (text no. 109) mention building activities carried out there by Sargon and the expansion of irrigation in the area of the city.

Melid

Although four texts on clay cylinders come from Melid (modern Arslantepe, near Malatya), they are all in fragmentary condition (text nos. 111–114). Only one (text no. 111) preserves part of the end of its inscription and no reference to any building work can be detected. The curse at the end of the text invokes the god Marduk, which might suggest that any structure or object whose construction or dedication was mentioned at the end of the inscription would have been associated with that deity.

Ḫarḫar and Iran

The Najafabad Stele states that following the king's conquest of the Iranian city of Ḫarḫar during his sixth regnal year (716), he renamed it Kār-Šarrukīn. In addition, as well as rebuilding a temple, he constructed something else there.[151] It is not known what that other structure was, although a later letter to the king from that city (Fuchs and Parpola, SAA 15 no. 94 [=Harper, ABL no. 126]) refers to the building of a "grand hall" (É dan-nu) with glazed bricks. Sargon's Khorsabad Annals also state that during the campaign of the following year (715) he rebuilt the cities Kišešlu, Kindayu, Anzaria, and Bīt-Gabaya and renamed them Kār-Nabû, Kār-Sîn, Kār-Adad, and Kār-Ištar (text no. 1 lines 113b–114a).

Babylonia

Following his defeat of Marduk-apla-iddina II (Merodach-Baladan) in 710–709, Sargon had work carried out at Babylon, Uruk, and likely Kish and Tell Haddad. Most of the texts mentioning this work are written in the Akkadian language, but three were composed in Sumerian (text nos. 124 and 127–128).

Bricks with inscriptions recording Sargon's restoration of Babylon's city walls, Imgur-Enlil and Nēmet-Enlil, for the god Marduk have been found at both Babylon and Kish (text nos. 123–124). Presumably the bricks found at Kish had been used for some work at the same time at that city or been taken there for reuse later. One of the inscriptions (text no. 123) also mentions that work had been carried out with baked bricks along the bank of the Euphrates River (presumably inside Babylon). Of the two texts, one is written in Akkadian and one in Sumerian. According to Sargon's annals from Khorsabad, the king had a new canal dug from Borsippa to Babylon for the procession of the god Nabû.[152]

One clay cylinder and several brick inscriptions testify to work carried out at the city of Uruk in southern Babylonia. The one cylinder records the restoration of Eanna, and in particular its outer enclosure wall in the lower courtyard (text no. 125), for the goddess Ištar. Numerous bricks found at Uruk record work on various parts of the Eanna temple, including the outer enclosure wall, the courtyard, the narrow gate, the regular gate, and the processional way (text nos. 126–128).

A clay cylinder of Sargon's was found at Tell Haddad in the Hamrin region (text no. 129). Although none of the building section of the text is preserved, it may have been intended to record work at that city, and in view of the fact that it was found not far from the temple of Nergal (Ešaḫula) at that site, it may well have mentioned work on that temple. A fragmentary axe head of one of Sargon's eunuchs was also found at Tell Haddad and the text on it recorded the dedication of the object to the god who dwelled in Ešaḫul(a) located inside the city Mēturna (Mê-Turnat) (text no. 2008). A clay cylinder (text no. 2009) from Tell Baradān, a neighboring site, appears to refer to the governor of Arrapḫa Nabû-bēlu-ka''in doing something because Sargon wanted to rebuild the wall of Sirara (a literary term for Mê-Turnat). The cylinder was likely created to commemorate the governor's work on that wall.

Notes

130 With regard to Sargon's building activities, see also Fuchs, RLA 12/1–2 (2009) p. 59 and PNA 3/2 p. 1244. The Assyrian Eponym Chronicle appears to state that a deity entered his/her new temple in 713. That temple may or may not be mentioned in this section. Note also the possible restoration of the entries for 720 and 719 in that chronicle (see below).

131 Text no. 43 lines 34–52; see also text no. 8 lines 29b–31a. Note also Sargon's renewal of a land grant originally made by Adad-nārārī III to three individuals in order to ensure offerings to the god Aššur (Kataja and Whiting, SAA 12 no. 19). Sargon gave the original grantees of the land (or their sons) "field for field" in another location so that they could continue to provide the offerings while he could take the land originally granted to them for the construction of Dūr-Šarrukīn. The text was composed at Nineveh in Sargon's ninth year (713). While Sargon states that he built the new city in order to make Assyria prosper, K. Radner argues that his "decision to move the court and the central administration to a new centre was in part motivated by the lack of acceptance and the active and fierce resistance his rule had met with in the Assyrian heartland" (HSAO 14 p. 325). Radner may well be correct in this matter; however, it is not really clear who actually did oppose Sargon and how they had done so, even though it seems probable that some or all of 6,300 Assyrian "criminals" deported to Hamath early in his reign had opposed his accession. For the movement of the capital from Kalḫu to Dūr-Šarrukīn, see Radner, HSAO 14 pp. 325–327.

132 For references in the texts to the initial work, including the making of bricks, the laying of foundation deposits, and the use of deportees, see in particular text nos. 2 lines 467b–469a and 473b–474a, 7 lines 153b–155a and 159b–160a, 8 lines 27b–28a and 31b–34a, 9 lines 49b–57a, 12 lines 23b–29, 13 lines 90–97a, 14 lines 28b–33a, 43 lines 57–61, 45 lines 40–44a, 46 lines 32b–36, and 47 lines 18–21. Samarians were among the people employed in the construction of the new city; see Cogan, Bound for Exile pp. 45–49 nos. 2.03–5. For information from contemporary letters on the actual building of the city, see S. Parpola in Caubet, Khorsabad pp. 47–77.

133 The word used for "inaugurated" is SAR-ru, an Assyrian stative form from the verb šurrû, "to begin; to inaugurate a building, to kindle a censor; to start, originate (said of eclipses and other natural phenomenon), to erupt, grow" (CAD Š/3 p. 358), and "to begin, start; inaugurate" (CDA p. 388).

134 One exemplar of text no. 9 informs us that these gods were invited to come to Dūr-Šarrukīn for a celebration (tašīltu) in the month Tašrītu (VII), i.e., in 707; see the on-page note to text no. 9 line 98. This celebration is distinct from the festival (nigûtu) in Ayyāru (II) of 706 to which numerous foreign rulers and important Assyrians were invited.

135 See in particular text nos. 2 lines 483b–494, 7 lines 167–186a, 8 lines 54–69a, 9 lines 97b–100, 12 lines 34–45, 13 lines 123b–130, and 15 lines 1´–5´. Mention of this festival in a text indicates that that text was composed no earlier than 706, unless we assume that they were recording an event that was planned, but that had not yet taken place.

136 See in particular text nos. 8 lines 49b–53, 9 lines 92b–97a, 41 lines 25b–26a, 43 lines 72–74, 44 lines 49b–54, 75 lines 10´–14´, and 84 line 11´.

137 See for example text nos. 8 lines 31b–34a, and 9 lines 49b–57a, and 43 lines 57–61.

138 See Reade, SAAB 25 (2019) pp. 85–86. For the building of the city walls and its gates, see in particular text nos. 8 lines 40b–49a, 9 lines 79b–92a, 43 lines 65–71, and 44 lines 47–49a. Note also Battini, CRRA 43 pp. 41–55 and RA 94 (2000) pp. 33–56. With regard to the building of the city wall, note Cogan, IEJ 56 (2006) pp. 84–95. For the connection of the length of the city wall and the king's name, see the earlier section on the name of the king.

139 For the building and decoration of the palace, including its gates, see in particular text nos. 2 lines 472b–483a, 7 lines 158b–166, 8 lines 35–40a, 9 lines 60b–79a, 11 lines 21b–46, 12 lines 30–33, 13 lines 97b–123a, 14 lines 33b–47, 41 lines 18b-25a, 43 lines 63–64, 44 lines 33–45, 45 lines 19–39, 46 lines 22–32a, 47 lines 14–17, 48 lines 6´b–7´, 74 viii 1´´–6´´, 75 lines 6´–9´, 84 line 10´, 85 line 6´, and 111 line 13. With regard to the bīt ḫilāni, see most recently Reade, Iraq 70 (2008) pp. 13–40; Erarslan, Akkadica 135 (2014) pp. 173–195; and Kertai, Iraq 79 (2017) pp. 85–104, especially pp. 97–101; see also the note to text no. 2 line 476. For the use of the term É.GAL.MEŠ, literally "palaces" but translated here as "palatial halls," for the palace complex, see the note to text no. 2 line 472.

140 For the construction of the temples, in particular the palace chapels, and the entry of the deities into them, see in particular text nos. 2 lines 469b–472a, 7 lines 155b–158a, 8 line 34b, 9 lines 57b–60a, 41 lines 17-18a, 43 line 62, 44 lines 28b–30, 45 lines 12b–18, 46 lines 14–21, 47 lines 11b–13, 48 lines 1´b–6´a, 75 lines 1´–5´, 84 line 9´, 85 line 5´, and 111 line 12. The deities are sometimes stated to have been born within Eḫursaggalkurkurra, the cella of the god Aššur within that god's temple Ešarra at the city Aššur; see text nos. 2 lines 469b–470a, 7 lines 155b–156a, and 111 line 12a (totally restored).

141 Bricks with these inscriptions have been found at Kalḫu and Nineveh, as well as Khorsabad. One of those from Khorsabad was found in the throne room of the palace.

142 With regard to this structure, see in particular Loud and Altman, Khorsabad 2 and note also Matthiae in Studies Donbaz pp. 197–203.

143 See text no. 10 ex. 4, text no. 11 commentary, text no. 43 exs. 13–21, 28, and 31–32, and text no. 57 Frgms. L and M.

144 See in particular text nos. 8 lines 28b–29a, 9 lines 41b–42, and 74 viii 7´´–9´´.

145 Text no. 84 line 3´–4´; cf. text no. 74 i 25–27.

146 See Haller, Heiligtümer pp. 89–92.

147 For an inscription of Adad-nārārī III recording work on the temple of Nabû at Nineveh, see Grayson, RIMA 3 pp. 219–220 A.0.104.14.

148 Text no. 92 states that Adad-nārārī III had carried out his work on the temple seventy-five years earlier and Reade suggests that Sargon may have restored it in 713 (Iraq 67 [2005] p. 380).

149 See Frahm, AoF 40 (2013) pp. 52–53. Note also Reade in Studies Calmeyer p. 612. Some bricks with inscriptions of Sargon II were found at Nebi Yunus (e.g., text no. 53 ex. 24 and text no. 54 ex. 4).

150 RLA 12/1–2 (2009) p. 59 and PNA 3/2 p. 1244.

151 Text no. 117 ii 41b–45a; see also text no. 1 lines 114–115.

152 Text no. 1 lines 377b–379a and text no. 2 lines 359b–360.

Grant Frame

Grant Frame, 'Building Activities', RINAP 2: Sargon II, Sargon II, The RINAP 2 sub-project of the RINAP Project, 2021 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap2/rinap2introduction/buildingactivities/]