Ashur (63-72)

063 064 065 066 067 068 069 070 071 072

063 [/rinap/rinap2/Q006544/]

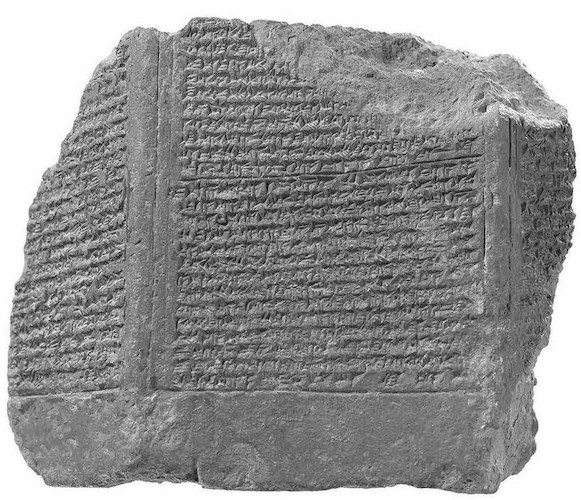

A fragment of a clay prism found at Aššur in 1910 records parts of the campaigns in 716–713, which are assigned in this text to the ruler's fifth through eighth regnal years (palûs), in line with the assignment found in the Nineveh Prism (text no. 82) and, as far as it is preserved, a tablet fragment in the Oriental Institute (text no. 102), and against that found in the Khorsabad Annals (text nos. 1–4) and (apparently) the Najafabad Stele (text no. 117), which assign the events to Sargon's sixth through ninth regnal years. The fragment describes campaigns against Mannea, Karalla, and Urarṭu. The text is commonly known as the Aššur Prism of Sargon II and C.J. Gadd refers to it as prism C (Iraq 16 [1954] p. 175). It is possible that the inscription on this fragment was simply a duplicate of what was on the Nineveh Prism (text no. 82), at least with regard to the section preceding the building report (see Tadmor, JCS 12 [1958] p. 24 n. 20). If this is correct, columns i´, ii´, and iii´ would likely duplicate parts of text no. 82 columns ii (towards the bottom of the column), iii (towards the bottom of the column), and iv–v (end of column iv and start of column v) respectively; see also Fuchs, SAAS 8 pp. 8 and 23–35. However, the two texts only overlap for a few lines: text no. 63 ii´ 6´–18´ ≈ text no. 82 iii 1´´´–17´´´ and text no. 63 iii´ 7´–14´ ≈ text no. 82 v 1–8. The Nineveh Prism was composed in Sargon's eleventh regnal year (711), or possibly the following year (710). Thus, if the two texts are duplicates, the Aššur Prism must also have been composed no earlier than 711.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap2/Q006544/] of Sargon II 063

Source:

Commentary

The prism originally had eight columns, of which the fragment preserves the ends of three. The restorations are based for the most part on those proposed by E. Weidner and A. Fuchs.

Assuming that the various prisms of Sargon bore basically the same text, Weidner estimated that each column of the Aššur prism had at least 120–150 lines, perhaps even 150–180 lines, and thus that the eight-sided prisms had originally 960–1,440 lines. He also estimated that the Aššur prism had been originally 32–48 cm high. (See AfO 14 [1941–44] pp. 40–41.)

The building portion of the inscription is not preserved, but the prism was found in the temple of the god Aššur. Since Sargon is known to have carried out work in that temple (see text no. 74 i 25–28 and text no. 84 line 3´), it is possible that the prism was commissioned to commemorate work on that temple. (See Fuchs, SAAS 8 p. 5.) On the bottom end of the prism fragment are found damaged representations of a stylized tree and an animal, possibly a kid. (For photographs of these, see Weidner, AfO 14 [1941–44] p. 48; Finkel and Reade, ZA 86 [1996] fig. 7 following p. 268; Fuchs, SAAS 8 p. ii; and Aššur excavation photograph S 4816.) The goat was an attribute of the god Aššur and thus its appearance on the fragment may support the supposition that the prism was created to commemorate work on the temple of that god. (See Finkel and Reade, ZA 86 [1996] pp. 246–247.) Designs are also found on the bottom of a prism from Nineveh, text no. 82; see the commentary to that text with regard to these representations.

Bibliography

Cols. i´–iii´ of VA 8424 (text no. 63), the Aššur Prism. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum. Photo by O.M. Teßmer.

064 [/rinap/rinap2/Q006545/]

A fragment of a hollow clay cylinder in the Vorderasiatisches Museum preserves part of an inscription of Sargon II that records the end of the description of his military campaign to Babylon in his twelfth and thirteenth regnal years (710–709), as well as the receipt of gifts from the ruler of Dilmun and from seven rulers on Cyprus (lines 1´–17´), and possibly the beginning of a building report (lines 18´–21´). The inscription may have been composed in 707 (see Frahm, KAL 3 p. 76).

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap2/Q006545/] of Sargon II 064

Source:

Commentary

The cylinder fragment was found in the area of the former New Palace at Aššur. Although part of the left edge of the piece is preserved, the beginnings of the lines are no longer preserved. As noted by E. Frahm (KAL 3 p. 76), lines 18´–21´ might be the beginning of a building report. While the mention of the "king of the gods" in line 21´ would make one think of the god Aššur and thus work on the temple of that god, he could also be mentioned in connection with work on other building projects, such as the royal palace. If, as Frahm suggests is possible, the provenance of the fragment points to the location of the building project for which the cylinder was intended, the report might deal with work on the city of Aššur's inner wall or processional street.

The restorations in lines 1´–17´ follow Frahm, KAL 3 p. 75 and are for the most part based on text no. 7 lines 134–149 and similar passages in other texts (e.g., text no. 74 vi 63–80 and vii 7–38; text no. 83 iii´ 1–13; and cf. text no. 103 iv 1–42), although for line 6´, see text no. 74 vi 80. The text has been collated by J. Novotny.

Bibliography

065 [/rinap/rinap2/Q006546/]

A large, four-column tablet with 430 lines of text was found in a private house in the city of Aššur and records a formal letter, written in the first person, from Sargon II to the god Aššur in which the ruler reports on a campaign conducted against the land Urarṭu and the city Muṣaṣir in the ruler's eighth regnal year (714). According to line 6, the campaign began in the month Duʾūzu (June–July) and a lunar eclipse that is mentioned in line 318 as an omen towards the close of the campaign and immediately before the attack on Muṣaṣir has been dated to the evening of October 24, 714. This indicates that the campaign lasted at least three or four months. The text was likely composed in 714 or soon thereafter. This text is commonly referred to as Sargon's Eighth Campaign, Sargon's Letter to the God, or Sargon's Letter to Aššur.

The inscription consists of an initial address (lines 1–5), the body of the text (lines 6–425), and a concluding statement/colophon (lines 426–430), which informs us that the tablet had been written by the royal scribe Nabû-šallimšunu, who was the son an earlier royal scribe, Ḫarmakki. The address (lines 1–5, with each line separated by a line ruling) invokes blessings on the god Aššur, the other deities who dwell in his temple Eḫursaggalkurkurra, the deities who dwell in the city Aššur, and the city Aššur itself, as well as all who dwell in it, in particular those living in its palace; and it concludes by stating that all was well with Sargon and his troops. The body of the text is divided by line rulings into fifteen sections. The first five sections (lines 6–166) describe the king assembling his troops, setting out on campaign, and proceeding through the Zagros Mountains, where he received tribute and gifts from vassal rulers and those who wanted to win his friendship and prevent hostile actions being directed against them. In order to help the Mannean ruler Ullusunu, his vassal, he met the forces of Rusâ (written Ursâ in this and numerous other inscriptions of Sargon II) and Mitatti, the rulers of Urarṭu and Zikirtu respectively, in battle on Mount Uauš, which resulted in a major Assyrian victory and the flight of Rusâ. Sargon then decided to break off his campaign to the lands of Andia and Zikirtu and set out for Urarṭu (line 162). Sections six through twelve (lines 167–305) record Sargon's march through Urarṭian territory. For the most part, the natives fled before the Assyrian advance and these sections provide a description of Urarṭu, including its irrigation works. The Assyrians carried out numerous destructive actions as they marched through Urarṭu. The thirteenth section (lines 306–308) simply records the receipt of tribute from Ianzû, the king of the land Naʾiri, indicating that Sargon had left Urarṭu and was on his way home. The fourteenth (and longest) section (lines 309–414) describes Sargon's decision to halt his journey back to Assyria as a result of the lunar eclipse mentioned earlier and instead take a small force to attack the city Muṣaṣir, a small state that bordered both Assyria and Urarṭu. Muṣaṣir was also a "holy city," sacred to the god Ḫaldi, a deity highly honored in Urarṭu; the text records that in this city Urarṭian kings were crowned. That city was captured, looted, and destroyed; and a long, detailed list of the booty taken from the palace of king Urzana and from the temple of Ḫaldi is given. The final section (lines 415–425) recapitulates the major achievements of the campaign. The exact route taken by Sargon during the course of this campaign is a matter of intense scholarly debate (see below).

A.L. Oppenheim has argued that texts of this type were "not to be deposited in silence in the sanctuary, but to be actually read to a public that was to react directly to their contents" and that "they replace in content and most probably in form the customary oral report of the king or his representative on the annual campaign to the city and the priesthood of the capital" (JNES 19 [1960] p. 143). With regard to letters of gods in general and this one in particular, see Borger, RLA 3/8 (1971) pp. 575–576; Oppenheim, JNES 19 (1960) pp. 133–147; and Pongratz-Leisten in Hill, Jones, and Morales, Experiencing Power pp. 295–301. For a letter to the god, likely coming from the reign of Shalmaneser IV, see Grayson, RIMA 3 pp. 243–244 A.0.105.3; for one from Esarhaddon, see Leichty, RINAP 4 pp. 79–86 no. 33. Although the text is written in Babylonian dialect, at times Assyrian dialectical features appear (e.g., lā for ul in line 84, iqabbûšuni for iqabbûšu in lines 11 and 188, and iṣbutū for iṣbatū in line 177). The Akkadian text is composed in a very literary style and is at times complicated, with regard to both syntax and content (Vera Chamaza, SAAB 6 [1992] p. 128) and, as V. Hurowitz has noted, many passages could be described as "poeticized prose" (Studies Ephʿal p. 105 n. 8). For these reasons, it is impossible to give a fully acceptable translation that at all times both reflects the Akkadian syntax accurately and does not violate the rules of good English.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap2/Q006546/] of Sargon II 065

Source:

Commentary

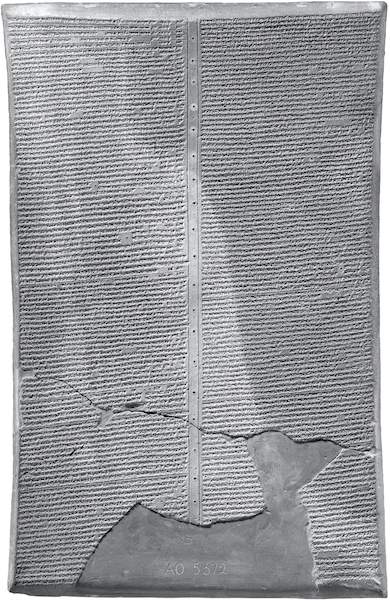

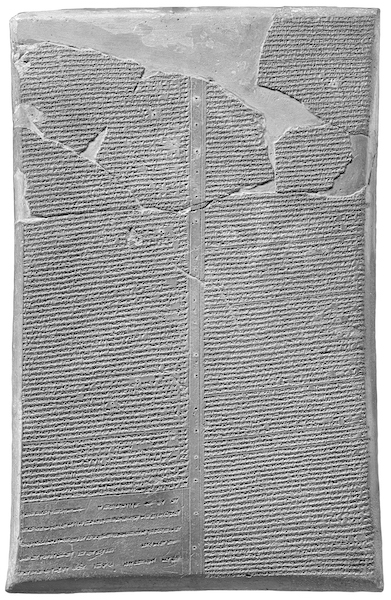

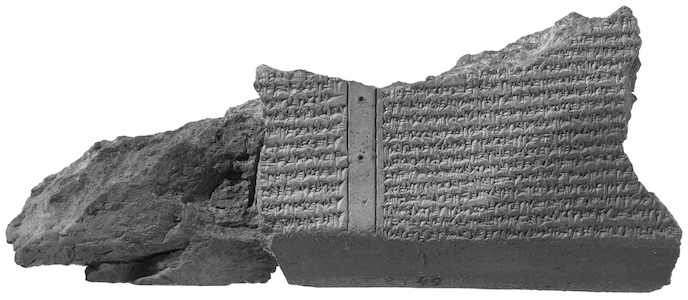

The tablet is made up of one large and several smaller pieces: AO 5372 + VAT 8634 (Ass 17681d) + VAT 8749 (Ass 17681a) + VAT 8698a–c (Ass 17681b,c,g). VAT 8634 and 8749 are shown on the Aššur excavation photograph 5280. AO 5372 was purchased by the Louvre Museum from the antiquities dealer Géjou in 1910. The fragments in the Vorderasiatisches Museum with the excavation number Ass 17681 were found at Aššur in 1910 in the house of the exorcist (hD81, excavation trench). The tablet is one of the largest cuneiform tablets known; the largest piece, AO 5372, measures 37.5×24.5×4 cm. Its four columns (two on the obverse and two on the reverse) have 109 (1–109), 114 (110–223), 110 (224–333), and 97 (334–430) lines respectively. The scribe, Nabû-šallimšunu, has placed a Winkelhaken to the left of the beginning of every tenth line. There are small holes at regular intervals along all four edges of the tablet and in the space between the two columns on each side of the tablet; the right edge, for example, has eleven holes.

Obverse of AO 5372, Sargon's letter to the god Aššur recording his eighth campaign (714).

© Musée du Louvre, dist. RMN - Grand Palais / Raphaël Chipault.

Reverse of AO 5372, Sargon's letter to the god Aššur recording his eighth campaign (714).

© Musée du Louvre, dist. RMN - Grand Palais / Raphaël Chipault.

There are numerous studies dealing primarily with the geographical and historical aspects of Sargon's eighth campaign. In particular, there has been a great deal of discussion over the route taken by Sargon. Did he encircle Lake Urmia or did he only go up its western side? Did he go around or even reach Lake Van? The first editor of this text, F. Thureau-Dangin (TCL 3), believed that Sargon went up the eastern side of Lake Urmia, continued over to Lake Van, and then went along the northern and western shores of that lake before returning to Assyria via Muṣaṣir. In 1977, however, L. Levine proposed a much shorter route, one that took Sargon around neither Lake Urmia nor Lake Van (Levine in Levine and Young, Mountains and Lowlands pp. 135–151). In a recent publication (Muscarella and Elliyoun, Eighth Campaign of Sargon II [2012]), studies by O.W. Muscarella and S. Kroll came to different conclusions, although both agreed that Sargon did not get close to Lake Van. Muscarella (following work by H.A. Rigg, L.D. Levine, and M. Salvini) believes that Sargon "campaigned solely along Lake Urmia's southern and western shores and adjacent districts before turning back to Assyria" (pp. 5–9, especially p. 8 [article reprinted in Muscarella, Archaeology, Artifacts and Antiquities pp. 523–530]), while Kroll (following work by P. Zimansky, M. Liebig, and J.E. Reade, and making use of an unpublished study by A. Fuchs) believes that Sargon went around Lake Urmia, although not always close to the coast (pp. 11–17). For the latter view, see also Fuchs in Yamada, SAAS 28 pp. 42–47. Recently, however, J. Marriott and K. Radner (JCS 67 [2015] p. 139) have argued that for reasons of food logistics the campaign cannot have gone around Lake Urmia and was more likely in the area southwest of that lake. See in addition the following studies: Bagg, Assyrische Wasserbauten pp. 130–132; Çilingiroğlu, Anadolu Araştırmaları 4–5 (1976–77) pp. 252–271; Danti, Expedition 56/3 (2014) pp. 27–33; Diakonoff and Medvedskaya, BiOr 44 (1987) pp. 388–391; Hipp, Folia Orientalia 24 (1987) pp. 41–46; Jakubiak, IrAnt 39 (2004) pp. 191–202; Kessler in Haas, Urartu pp. 66–72; Kleiss, AMI NF 10 (1977) pp. 137–141; Kroll in Köroğlu and Konyar, Urartu pp. 160–162; Lehmann-Haupt, MVAG 21/3 (1916) pp. 119–151; Levine in Levine and Young, Mountains and Lowlands pp. 135–151; Liebig, ZA 81 (1991) pp. 31–36 and ZA 86 (1996) pp. 207–210; Mayer, MDOG 112 (1980) pp. 13–33; Medvedskaya in Parpola and Whiting, Assyria 1995 pp. 197–206; Muscarella, JFA 13 (1986) pp. 465–475; Reade, Iran 16 (1978) pp. 137–143; Reade in Liverani, Neo-Assyrian Geography pp. 31–42; Rigg, JAOS 62 (1942) pp. 130–138; Salvini, BiOr 46 (1989) p. 399; Salvini in Pecorella and Salvini, Tra lo Zagros, particularly pp. 15–16 and 46–51; van Loon, JNES 34 (1975) pp. 206–207; Vera Chamaza, AMI NF 27 (1994) pp. 91–118 and AMI NF 28 (1995–96) pp. 235–267 (esp. p. 239 fig. 1 and pp. 253–264); Wiessner, AfO 44–45 (1997–98) pp. 146–155; Wright, JNES 2 (1943) pp. 173–186; Zimansky, Ecology and Empire pp. 40–47; and Zimansky, JNES 49 (1990) pp. 1–21. An important unpublished study of the topography and history of the Zagros region by Fuchs was completed in 2004 (Bis hin zum Berg Bikni: Zur Topographie und Geschichte des Zagrosraumes in altorientalischer Zeit [Tübingen University, 2004]).

There are several abrupt digressions within the section dealing with the city Muṣaṣir. K. Kravitz (JNES 62 [2003] pp. 81–95, especially pp. 94–95) has argued that lines 336–342, 347b–348a, and 411–413 were added to the episode of the sack of that city "when it was already essentially completed" and that the additions "shifted the ultimate outcome of the episode from the punitive plundering of the rebellious Muṣaṣirian vassal to the symbolic disempowerment of the Urarṭian king" (ibid. pp. 81 and 94–95).

V. Hurowitz notes that the total number of lines in the text (including the colophon) is the same as the number of Urarṭian settlements that Sargon claims to have captured (line 422) and argues that "Presenting to the god a 430 line text imitated symbolically the tribute Sargon offered from the 430 cities he conquered" (Studies Ephʿal pp. 107–108).

The inscription refers to Rusâ (Ursâ) as being ruler of Urarṭu at the time of this campaign, but there is some discussion over which Rusâ this was, Rusâ son of Erimena or Rusâ son of Sarduri. Thureau-Dangin thought it was Rusâ son of Erimena, but this view was later opposed by C.F. Lehmann-Haupt who argued for Rusâ son of Sarduri. The latter's view has predominated in recent scholarship (e.g., Fuchs, PNA 3/1 pp. 1054–1056 sub Rusâ 1; and Salvini, Biainili-Urartu p. 133). M. Roaf has recently argued that Thureau-Dangin was correct and that the Urarṭian ruler mentioned in this text was Rusâ son of Erimena (Aramazd 5/1 [2010] pp. 66–82; CRRA 54 pp. 771–780; and Biainili-Urartu pp. 187–216).

Obverse of VAT 8749 (text no. 65, lines 99–109 and 207–223), Sargon's letter to the god Aššur recording his eighth campaign (714). © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Vorderasiatisches Museum. Photo by O.M. Teßmer.

Bibliography

066 [/rinap/rinap2/Q006547/]

A brief inscription of Sargon is found upon some glazed wall plaques for clay cones from Aššur. This is the only royal inscription known that states that Sargon was the son of Tiglath-pileser III. For a letter that might also indicate that Sargon was the son of Tiglath-pileser (Dietrich, SAA 17 no. 46 [=CT 54 no. 109]), see Thomas, Studies Bergerhof pp. 467–470.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap2/Q006547/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q006547/score] of Sargon II 066

Sources:

| (01) EŞ 3282 | (02) VA Ass 2332a–d + VA Ass 2366b (Ass 31) | (03) Ass 46 |

| (04) VA Ass 2333a+c–h | (05) VA — | (6) VA — (Ass 14?) |

| (7) VA Ass 3512 | (8) VA Ass 3512 |

Commentary

According to E. Unger, ex. 1 came from the royal palace at Aššur, but no excavation number or excavation photo number is known for it. Thus, it is edited from the published copy by Unger, with some help from the published photographs. A. Nunn (Knaufplatten p. 107 no. 61) states that EȘ 3282 (ex. 1) is the current museum number for Ass 46 (ex. 3) and that it measures 31×31×3 cm; however, O. Pedersén (Katalog pp. 110 and 215) and F. Pedde and S. Lundström (Palast p. 182 n. 275) treat them separately. The two are kept separate here, but Nunn may be correct in identifying them as one and the same piece. Nunn (Knaufplatten p. 107 no. 62) notes that while the excavation journal says that ex. 2 was found in gB5I, the inventory book indicates it was found in gA5II. Ex. 3 is made up of seven large and several small pieces. Ex. 4 is made up of five joined fragments, as well as several separate pieces with no traces of an inscription. The inscriptions on exs. 1, 2, and 4 are written counter-clockwise around the middle of the plaque (the area in which the peg for the cone was placed). The signs on ex. 4 are quite faint.

All information on exs. 5–8 comes from Nunn (Knaufplatten p. 117 nos. 269–272), who states that the four pieces (like the preceding exemplars) come from glazed square plaques for cones. She considers ex. 5 to have two inscriptions, one above on the molding ("Profilleiste") ([...] MAN GAL MAN dan-nu [...]) and one below on the plate itself ([...] KUR aš-šur A mtukul-ti-[...]); they are treated here as parts of the same inscription. She also notes that the inscription on ex. 5 is written from the inside out ("von innen nach außen") rather than the normal direction, from the outside in ("von außen nach innen"). Very little of the inscription on exs. 6–8 is preserved and no part of the royal name; thus, their assignment to this inscription is not completely certain.

Bibliography

067 [/rinap/rinap2/Q006548/]

This inscription is found on several clay cones and one unidentifiable clay object from Aššur. It records the king's work on Eḫursaggalkurkurra, the cella of the temple of the god Aššur and was written in the fifth month of the eponymy of Nasḫur-Bēl (705). For brick inscriptions of Sargon recording work on Eḫursaggalkurkurra, see text nos. 69–70; note also text no. 84 line 3´ and likely text no. 74 i 25–27.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap2/Q006548/] or the score [/rinap/scores/Q006548/score] of Sargon II 067

Sources:

| (01) A 3647 (Ass 3327) | (02) A 3364 (Ass 1742) | (03) A 3378 (Ass 2927a) |

| (04) A 3379 (Ass 2927b) | (05) A 3380 (Ass 3000) | (06) A 3582 (Ass 16007) |

| (07) A 3598 + A 3599 + VA Ass 2071 (Ass 17342a + Ass 17342b + Ass 17404) | (08) A 3653 (Ass 3143) | |

| (09) Ass 4397 | (10) VA Ass 2070 (Ass 4572 | (11) A 641 (Ass 17791) |

| (12) VA 5159 |

Commentary

Assur photo 320 depicts several clay cones with this inscription (supposedly exs. 1–5 and 8), but the inscriptions on them are not legible. According to O. Pedersén (Katalog, pp. 133 and 148) exs. 9 and 11 are fragments of glazed clay cones. Ex. 12 is listed under his category "Other Clay Objects" ("Sonstige Tongegenstände") (ibid. p. 223). The line arrangement follows ex. 1, but the master line is a composite from various exemplars. Ex. 12 has lines 7–8 on one line.

Bibliography

068 [/rinap/rinap2/Q006549/]

A large number of bricks from the city of Aššur are inscribed with a brief four-line building inscription of Sargon II dedicated to the god Aššur. Many of these bricks were found in or near the temple of that god.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap2/Q006549/] of Sargon II 068

Sources:

| (01) Ass 1519 | (02) Ass 740 | (03) Ass 775 |

| (04) Ass 826 | (05) Ass 1521 | (06) Ass 1482 |

| (07) Ass 776 | (08) VA Ass 3276a (Ass 2794) | (09) VA Ass 3276b (Ass 3280) |

| (10) VA Ass 3276c | (11) VA Ass 3276d | (12) VA 6914 (Ass 2970a) |

| (13) VA Ass 3276e | (14) VA Ass 3276f | (15) Ass 11944 |

| (16) Ass 816 | (17) Ass 1690 | (18) EŞ — (Ass 2970b) |

| (19) Ass 3054 | (20) EŞ — (Ass 3079) | (21) Ass 3166 |

| (22) Ass 3175 | (23) Ass 3285 | (24) Ass 3286a |

| (25) Ass 3289 | (26) Ass 4005 | (27) Ass 4411 |

| (28) Ass 5577 | (29) — | (30) EŞ 6669? |

Commentary

Pedersén, Katalog p. 162 indicates that exs. 3, 4, or 7 may be the brick depicted on Assur photo 999 (ex. 29). According to Messerschmidt, KAH 1 no. 39, these exemplars (at least those that are preserved at the relevant point) have ana not a-na in line 4; the brick depicted on the photo has ⸢a?/DIŠ⸣-na. The Vorderasiatisches Museum has a composite excavation copy ("Fundkopie") of exs. 3, 4, and 7; although this copy has been consulted, it has not been used here since it does not record any variants that are not known elsewhere and since it is clear that at least one of the exemplars was not fully preserved (ex. 4, see Assur photo 158). J. Marzahn and L. Jakob-Rost (Ziegeln 1) erroneously give the museum number of ex. 9 as VA Ass 3276h. The provenance of this exemplar is given as hD4I by Marzahn and Jakob-Rost (ibid. p. 131 no. 348); the provenance in the catalogue follows O. Pedersén. The excavation number of ex. 10 is not known; it is erroneously given as Assur 18540 in Marzahn and Jakob-Rost, Ziegeln 1 p. 131 no. 349. There is an excavation copy for Ass 2970 and it is assumed here that it represents both exs. 12 (Ass 2970a) and 18 (Ass 2970b). The measurement of ex. 14 follows Marzahn and Jakob-Rost, Ziegeln 1 p. 133 no. 353. Jakob-Rost and Marzahn, VAS 23 p. 9 no. 124 gives that exemplar the measurements 10.5×16.0 cm and does not take it to be an exemplar of this inscription, but it seems likely that it is. Ex. 28 is edited from an excavation copy. The museum number of ex. 30 is not clear and the brick could be 6676 (information courtesy H. Galter). It is possible that ex. 30 is to be identified with one of the exemplars only known by its excavation number, particularly exs. 18, 20, or 21 that were assigned to the museum in Istanbul.

All exemplars known are inscribed, not stamped. There are no known deviations from the line arrangement given below and the master line follows ex. 1.

Exs. 6 and 27 are glazed. According to Andrae, MDOG 22 p. 37, ex. 2 is also a glazed brick, but neither KAH 1 p. X nor Pedersén, Katalog p. 162 indicates this. Pedersén (ibid. p. 171) indicates that ex. 22 has a glazed rosette on it. Ass 16596 (found in iC4III) is said to be a fragment of a "gestempelt" glazed brick of Sargon II, but nothing more is known about it (idid., p. 194; cf. Gries, Assur-Tempel p. 257 no. 2092).

Haller, Gräber p. 36 refers to a brick of Sargon (II) from the Aššur temple being found in grave 456 (bE5V). This should refer to one of text nos. 68–70; the brick is said to measure 41×41 cm, which might suggest either text no. 69 or text no. 70, rather than text no. 68.

According to the Aššur excavation records, Ass 3144 and Ass 3230A are brick fragments which have four inscribed lines each and which can be assigned to Sargon II. Nothing further is known about the inscriptions on them; they may have this inscription or some other inscription of this ruler. Ass 3144 was found in hE4I, court, southeast, and Ass 3230A was found in hD4I, court, middle. Bricks with this inscription were found with the same map coordinates (exs. 12 and 21–23). See Pedersén, Katalog p. 171 and Gries, Assur-Tempel p. 267 no. 2317.

As is the practice in RINAP, no score for this brick inscription is given on Oracc, but the minor variants are listed at the back of the book.

Bibliography

069 [/rinap/rinap2/Q006550/]

This inscription from Aššur records the paving of the processional way of the courtyard of Eḫursaggalkurkurra, the cella of the temple of the god Aššur. It is inscribed on a large number of bricks, many of which were found in or near the temple of that god. The next inscription (text no. 70) is a Sumerian version of this Akkadian text.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap2/Q006550/] of Sargon II 069

Sources:

| (01) VA 6925 (Ass 1800) | (02) Ass 1598a) | (03) Ass 1598b |

| (04) Ass 723 | (05) Ass 1525 | (06) Ass 1573 |

| (07) Ass 1586 | (08) Ass 1595 | (09) Ass 1635 |

| (10) VA 6934 (Ass 3298) | (11) VA Ass 3275a (Ass 9344) | (12) VA Ass 3275b (Ass 20950) |

| (13) VA Ass 3275c | (14) Ass 19168 | (15) Ass 19167 |

| (16) Ass 988 | (17) Ass 1501 | (18) Ass 1884 |

| (19) Ass 2204 | (20) Ass 2258 | (21) Ass 2367 |

| (22) Ass 2381 | (23) Ass 2394 | (24) Ass 2798 |

| (25) Ass 3007 | (26) Ass 3019 | (27) Ass 3139 |

| (28) Ass 3277 | (29) Ass 3587 | (30) Ass 3652 |

| (31) Ass 3687 | (32) Ass 3757 | (33) Ass 3772 |

| (34) Ass 3773 | (35) Ass 3788 | (36) Ass 3793 |

| (37) Ass 3794 | (38) Ass 3859 | (39) Ass 3898 |

| (40) Ass 5581 | (41) Ass 7289 | (42) Ass 13366 |

| (43) Ass 17969 | (44) EŞ — | (45) EŞ 6677 |

Commentary

The findspot given above for ex. 1 follows Pedersén, Katalog p. 166; Andrae, AAT p. 91 states that this brick came from iE5I. Ex. 4 has been edited using the excavation photograph and an excavation copy ("Fundkopie") in the Vorderasiatisches Museum. The excavation photograph of ex. 6 has been consulted, but it was not possible to confirm large parts of the text from it. For ex. 10, Marzahn and Jakob-Rost, Ziegeln 1 p. 129 no. 343 gives the Assur number 3298e; the catalogue follows Pedersén, Katalog p. 172. The provenance for ex. 12 is given as "Sin-Šamaš-Tempel; fc 6III" in Marzahn and Jakob-Rost, Ziegeln 1 p. 130 no. 345; for greater details on the findspot, see Pedersén, Katalog p. 203 and p. 49 sub Ass 20948. Exs. 16 and 17 are edited from excavation copies. O. Pedersén (Katalog p. 179) says that Ass 3859 (ex. 38) was found in hB4I, while H. Gries (Assur-Tempel) p. 268) states that it was found in hC4I. Ass 5581 (ex. 40) actually refers to fragments of two bricks (see Pedersén, Katalog p. 180). Ass 3898 refers to several fragments of pavement bricks that have text nos. 69 and 70 (see Pedersén, Katalog p. 175); thus, ex. 39 may represent more than one exemplar. It is not certain that the inscription on ex. 41 is a duplicate of this text; see Pedersén, Katalog p. 183. It is quite possible that the two exemplars seen in Istanbul (exs. 44–45) also appear in the catalogue under their excavation numbers. H. Galter kindly supplied information on exs. 44–45 as well as photographs of them.

All exemplars that have been checked are inscribed, not stamped, and all have the same line arrangement. The master line follows ex. 1.

Bricks recording the construction of the processional way of the Aššur temple (this inscription and text no. 70) were found at that temple (see also Andrae, MDOG 44 [1910] pp. 47–48 and fig. 16, and Haller, Heiligtümer pp. 62–63) and in such other structures as the palace of Ashurnasirpal II (see Preusser, Paläste p. 23 and text no. 70 exs. 2–3), the Sîn-Šamaš temple (see Haller, Heiligtümer p. 89 and ex. 12), and the Anu-Adad temple (see Andrae, AAT pp. 91–93).

No score for this brick inscription is given on Oracc, but the minor variants are listed at the back of the book.

Bibliography

070 [/rinap/rinap2/Q006551/]

This inscription is a Sumerian version of the previous Akkadian inscription recording the paving of the processional way of the courtyard of Eḫursaggalkurkurra. Most of the exemplars with this inscription were found in the temple of the god Aššur at Aššur.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap2/Q006551/] of Sargon II 070

Sources:

| (01) Ass 1801 | (02) Ass 82 | (03) Ass 1500 |

| (04) Ass 1582 | (05) Ass 1598d | (06) Ass 1496 |

| (07) Ass 13367 | (08) Ass 3174 | (09) — |

| (10) Ass 3898 |

Commentary

The findspot given above for ex. 1 comes from Pedersén, Katalog p. 166 (see also KAH 1 p. X); Andrae, AAT p. 91 states that this brick came from iE5I. Large portions of the inscription on ex. 2 are not really legible on Ass ph 195. The excavation copies ("Fundkopie") of exs. 2–3 in the Vorderasiatisches Museum have been used, but these are of limited help. It is not certain that the six-line text reported to be on ex. 8 is actually a duplicate of this inscription; see Pedersén, Katalog p. 171. Ex. 9 is only known from a Babylon photo. Since some items depicted on Babylon photographs are known to have come from Aššur, it is likely that this piece did as well. It may even be one of exs. 2–8 or 10. Ass 3898 (ex. 10) refers to several fragments of pavement bricks on which are found text nos. 69 and 70.

A brick found in hE3V and depicted on Ass ph 5216 may have this inscription as well; see Gries, Assur-Tempel p. 264 no. 2262 and pl. 61d.

With regard to the use of bricks with this inscription in structures other than the Aššur temple, see the commentary to text no. 69.

The line arrangement for the text is the same for all exemplars and the master line follows ex. 1. No variants to the inscription are known and no score is presented on Oracc.

Bibliography

071 [/rinap/rinap2/Q006552/]

A poorly preserved glazed-brick frieze from the temple of the god Aššur at Aššur has some epigraphs on it that are likely to be attributed to Sargon II and to refer to events connected with that ruler's eighth campaign (714).

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap2/Q006552/] of Sargon II 071

Source:

Commentary

Only a small portion of the frieze has been published and this depicts a mountainous region, with an individual (king?) in a chariot, accompanied by several other soldiers, and a king enthroned. Several pieces are clearly misplaced and W. Andrae thought that the frieze had been patched together in ancient times with pieces from more than one scene (FKA pp. 11–12). According to an inventory book in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, some of the bricks making up the frieze bear the museum numbers VA Ass 2283–2286 (information courtesy J. Marzahn). The edition is based upon Andrae's published drawing.

Following E. Weidner, we can distinguish five groups of signs on the frieze:

1. ina bi-rit, "between"

2. e-tiq, "I/He traversed"

3. KUR.ni-⸢kip⸣-pi, "Mount Ni[k]ippa"

4. KUR.ú-pa-a KU₆-ub, "Mount Upâ I/He entered"

5.1. KUR.⸢si?-mir⸣-[ri-a], "Mount [S]imir[ria]"

5.2. ⸢KUR⸣.ú-x [...], "Mount U[...]," or ⸢KUR⸣-ú x [...], "mountain [...]"

In group 1, the rit sign is presented upside down. Groups 2 and 3 are on bricks in the same row, but separated by the figure of the individual in a chariot. Group 5 is found on one brick in the upper right corner of the frieze, in the same row as group 1; it has parts of two lines of inscription. Also following Weidner, we tentatively divide these five groups into three epigraphs (groups 1, 3, and 4; group 2; and group 5). This assumes that e-tiq (group 2) was at the end of an epigraph to the left of the section preserved here.

The ruler to whom the glazed-brick frieze is to be attributed has been a matter of discussion. Andrae and A. Haller assigned it to Tiglath-pileser I, B. Meissner (DLZ 46 [1925] col. 419) and A. Fridman to Tiglath-pileser III, and Weidner, A. Nunn, and P.R.S. Moorey (Materials p. 317) to Sargon II. The relief has been thought to represent Sargon's eighth campaign. See in particular text no. 65 lines 15 (for groups 1, 3, and 4), 16 (for group 2), 18 (for group 5), and 418 (for groups 1, 3, and 4).

Other fragments of inscribed glazed bricks have been found in this temple, but these are poorly preserved and their assignment to Sargon II is far from certain. A few better preserved fragments were found tumbled down in the court of the Aššur temple or walled up in later buildings (especially in temple A). Weidner gives two examples:

A. Ass 1024+1026: [šu]-lum NUMUN-šú šá-⸢lam⸣ [URU-šú], "[the well]-being of his offspring, the well-being [of his city]." Ass 1024 was found in iE5I (eastern prosthesis, eastern slope) and Ass 1026 in iC5I (southern prosthesis, under the Parthian building); the pieces were assigned to the museum in Istanbul. The first part of the inscription (up to and including the šá) is edited from an excavation copy ("Fundkopie") of Ass 1024 in the Vorderasiatisches Museum; the latter part of the inscription is based on Weidner's edition (AfO 3 [1926] p. 5). See Andrae, MDOG 22 (1904) pp. 13–14 and Pedersén, Katalog p. 163.

B. Ass 5268e, g: ⸢pít-ḫal?-lum⸣, "horseman." The piece was found in iB4III; it is shown on Ass ph 1763 and 1765 and has been collated from Ass ph 1763. See also Pedersén, Katalog p. 179. It cannot be considered absolutely certain that these two fragmentary texts should be assigned to the time of Sargon II, but it has been thought advisable to include them here.

In addition, Ass 16596 (found in iC4III) is a glazed brick fragment which is reported to have a stamped inscription of Sargon II; see Pedersén, Katalog p. 194. Ass 5269e, s, a fragment of a glazed brick found in iB4III, may also bear an inscription of this ruler; see ibid. p. 179.

With regard to the provenance of the frieze, see in particular Haller, Heiligtümer p. 58 fig. 17 no. 12 and pp. 60–61; see also Andrae, MDOG 43 (1910) pp. 34 and 36–38, and 44 (1910) pp. 45–47. With regard to glazed bricks and glazed-brick friezes in general, see Moorey, Materials and Industries pp. 312 and 315–322. For the glazed-brick friezes from Aššur in the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, see Fügert and Gries in Fügert and Gries, Glazed Brick Decoration pp. 28–47.

Bibliography

072 [/rinap/rinap2/Q006553/]

A fragment of part of the right side of a clay tablet in the Vorderasiatisches Museum (VAT 10716) preserves part of an inscription of Sargon II that appears to refer to Kibaba (city ruler of Ḫarḫar) and Daltâ (king of Ellipi), thus likely to the Assyrian campaign into Iran during Sargon's sixth regnal year (716). The piece has several so-called "firing holes" in it. It is not certain which side is the obverse and which the reverse. Side A has been collated, but the edition basically follows that published by E. Frahm. The inscription on side B is almost completely worn away and the transliteration of it is based solely on the published copy.

Access the composite text [/rinap/rinap2/Q006553/] of Sargon II 072

Source:

Bibliography

Grant Frame

Grant Frame, 'Ashur (63-72)', RINAP 2: Sargon II, Sargon II, The RINAP 2 sub-project of the RINAP Project, 2023 [http://oracc.org/rinap/rinap2/rinap2textintroductions/ashur6372/]