Royal marriage alliances and noble hostages

Assyrian foreign policy was not all about war. Diplomatic marriages with foreign dynasties and the exchange of noble hostages were designed to protect international treaties and guarantee peace.

Assyrian princesses marrying abroad

A rock crystal vessel bearing an inscription of Atalia, queen of Sargon II. Iraq Museum, IM 124999. Reproduced from M. S. B. Damerji, Gräber assyrischer Königinnen aus Nimrud, Mainz 1999, 46 fig. 24 (top right). View large image.

Sargon II (721-705 BC) gave one of his daughters in marriage to the Anatolian prince Ambaris of Bit-Purutaš, a kingdom in the region of modern Kayseri. The princess's dowry was the country of Hilakku, and its union with Bit-Purutaš made Ambaris the ruler over the most important principality of Tabal, as the area southeast of the Great Salt Lake (Tuz Gölü) was known in the early first millennium BC. Ambaris' new kingdom was to serve as a powerful pro-Assyrian buffer state against Urartu and Phrygia. Sargon's royal inscriptions which detail this arrangement do not mention the princess's name but it is known to us as Ahat-abiša from a reference in a letter of her brother, crown prince Sennacherib, to their father Sargon: "They have brought me from Tabal a letter from Nabu-le'i, the major-domo of (the lady) Ahat-abiša. I am herewith forwarding it to the king, my lord" (SAA 1 31). In 713 BC, the ambitious Ambaris betrayed Sargon and entered an alliance with Rusa of Urartu and Mita of Phrygia. As a consequence, he lost his kingdom and his freedom. Bit-Purutaš was turned into the (short-lived) Assyrian province of Tabal and Ambaris, his family, presumably including his wife Ahat-abiša, and the nobles of his country were deported to Assyria.

The case of Ahat-abiša's marriage to Ambaris is a rare occasion where a diplomatic marriage is referred to in the Assyrian royal inscriptions. It is of course mentioned only in order to emphasise just how appalling Ambaris' ingratitude towards his benefactor Sargon was. But it was certainly common Assyrian practice to secure an alliance with a foreign power by marriage. However, explicit references are exceptional. Another instance is mentioned in an oracle query of Esarhaddon (680-669 BC) which shows that this Assyrian king contemplated a treaty combined with a royal marriage match with Bartatua, king of the Scythians, imploring the gods' guidance on whether to send the Scythian one of his daughters in marriage (SAA 4 20).

Assyrian kings, too, could marry foreign royalty. On the basis of their names Yaba and Atalia which, unlike the names of most earlier and later Assyrian queens, are West-Semitic rather than Assyrian, it has been suggested that the wives of Tiglatpileser III (744-727 BC) and Sargon II were princesses from a western kingdom. By the time of Sargon, most of these dynasties had been extinguished, with the integration of their countries into the Assyrian provincial system, and it is possible that Sargon's wife Atalia, who shares her name with a 9th century Judean queen, may have been a princess of Judah, at the time one of the few remaining independent vassal states on the Eastern Mediterranean coast.

Captive princes and their royal brides

Sargon's daughter Ahat-abiša was sent to live in her husband's Anatolian mountain realm. Other Assyrian princesses, however, stayed at court with their royal spouses. One of them was married to the Egyptian prince Shoshenq who is known to us from witnessing the sale of a house in Nineveh in 692 BC (SAA 6 142) as "Šusanqu, the king's brother-in-law". The fact that he is named as the first witness signals his importance and his title (hatan šarri) indicates that he is related to the Assyrian king by marriage. A possible candidate for Shoshenq's royal wife is Šadditu, a daughter of Sennacherib (704-681 BC) who is attested in another legal document from Nineveh during her brother Esarhaddon's reign (SAA 6 251). But it is of course pure chance that her name happens to survive in our fragmentary source record and Shoshenq's bride could have been another daughter, or sister, aunt or cousin, of Sennacherib.

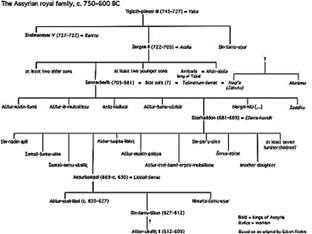

The family tree of the Assyrian royal family, c. 750-600 BC, including Atalia, Ahat-abiša and Šadditu. View large image.

Unlike Ahat-abiša, however, Shoshenq's unknown princess bride and her husband remained at the Assyrian court after their marriage. This alone makes it clear that Shoshenq was a royal hostage. His name is Libyan and identifies his origin as Egyptian, most likely from the Nile Delta region where several rulers and princes of that name are attested in the early first millennium BC. Our Shoshenq most probably arrived at Nineveh after the Assyrian army had met Kushite and Egyptian troops in 701 BC on the battlefield at Eltekeh in southern Palestine, not far from the Philistine city of Ekron. According to Sennacherib's inscriptions, he "captured alive in the heat of battle the charioteers and sons of the Egyptian kings (DUMU.MEŠ LUGAL.MEŠ KUR.mu-uṣ-ra-a-a), together with the charioteers of the king of the land Meluhha (= Kush)". Shoshenq, attested as a royal in-law in 692 BC, is most probably one of the Egyptian princes captured a decade before at Eltekeh.

Sennacherib's account makes it clear that from the Assyrian point of view, and despite the recently established supremacy of Kush, there were still Egyptian rulers considered powerful enough in their own right to be described as kings. This being the case, the Assyrian foreign policy would have taken these rulers into account as a matter of course and linking the captured noblemen to Assyria was a sensible strategy at a time when the Empire started to take an increasingly active interest in Egypt, designed to thwart Kushite dominion. Marrying the Delta princes to members of the Assyrian royal family gave them status and a role at court that went far beyond that of simple prisoners of war and provided Assyria with diplomatic and political currency when dealing with Egypt and Kush.

Royal hostages at the Assyrian court

Swearing a treaty, as depicted on the so-called Antakya Stela of Adad-nerari III of Assyria (810-783 BC). Archaeological Museum of Antakya, Inv. no. 11832. Photo by Marco Prins, from Livius [http://www.livius.org/as-at/assyria/treaty.html]. View large image.

Shoshenq may have been taken prisoner in battle before becoming a hostage at the Assyrian court. Many other hostages, however, were handed over by their families as part of a treaty agreement with Assyria. In addition to swearing loyalty oaths, subject rulers had to secure their treaties with Assyria when accepting the Empire's sovereignty by handing over members of their immediate family and sometimes also other high-born individuals. These hostages (līṭu) were then raised at the royal court of Assyria where their presence served a twofold purpose. While in Assyria, they were to guarantee their family's, and country's, loyalty to the Assyrian king with their life. Moreover, were they to return to their native land, ideally as its ruler or in another influential position, then the time spent at the Assyrian court was meant to have attuned them to Assyrian sensibilities and hence ensure their dependable conduct at home.

The practice is perhaps best attested for Sennacherib's reign when we know of several rulers who had lived at the Assyrian court before returning to rule their native country in line with Assyria's wishes: Bel-ibni, whom Sennacherib appointed as king of Babylon in 703 BC, "had grown up like a puppy in my palace" (or, given the timing, rather his father Sargon's palace) while Tabua, whom Esarhaddon made queen of the Arabs, "was raised in the palace of my father (Sennacherib)" according to the royal inscriptions. From these statements, we learn that these royal hostages at least were children when they were sent to the Assyrian court – an obvious advantage for the objective of pro-Assyrian indoctrination.

But at least in some cases, the distinction between hostage and protégé is blurred as, every so often, foreign dynasts had reason to see the Assyrian court as a safe heaven for their children, especially in times of upheaval back home. When Merodach-baladan of Bit-Yakin was proclaimed king of Babylon, Balassu of the rival Chaldean tribe of Bit-Dakkuri fled with his family to Sargon II. When the Assyrian king managed to regain control over the south, Balassu had already died but his son and daughter were sent from the Assyrian court to Borsippa, their dynasty's stronghold, in a move that successfully promoted loyalty to Assyria in that city (SAA 17 1; SAA 17 73).

Further reading:

Dalley, 'The identity of the princesses in Tomb II', 2008.

Zawadzki, 'Hostages in Assyrian Royal Inscriptions', 1995.

Content last modified: 20 Jul 2021.

Karen Radner

Karen Radner, 'Royal marriage alliances and noble hostages', Assyrian Empire Builders, University College London, 2021 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/aebp/essentials/diplomats/royalmarriage/]