Nineveh, Assyria's capital in the 7th century BC

From the reign of Sennacherib (r. 704-681 BC) onwards, Nineveh was the capital of the Assyrian empire. It was then considered to be the world's largest city: according to the Old Testament book of Jonah, it was home to 120,000 people and took three days to cross.

An old and important settlement

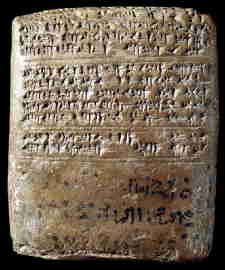

In this letter to Amenhotep III, king Tušhratta of Mittani informs the pharaoh that, as requested, he has sent a statue of the goddess Ištar/Šawuška of Nineveh to Egypt. The cuneiform tablet was excavated at Tell el-Amarna as part of the Egyptian state archives known today as the Amarna Letters, c. 1370-1350 BC, British Museum, ME 29793 (= EA 23). Photo © The British Museum. View large image on the British Museum's website.

Nineveh PGP is situated on the eastern bank of the Tigris PGP , where the river Khosr joins it, at a prime location in the long-distance trade network that crosses the Middle East. Today Mosul, Iraq's second largest city, covers parts of the area of the ancient Assyrian settlement.

Thousands of years before Sennacherib moved his royal court to Nineveh and transformed the city into Assyria's political and administrative centre, Nineveh was one of northern Mesopotamia's most important settlements. But our knowledge of these periods is limited, as archaeological investigations have focused on the impressive architecture of the 7th century BC. Yet a deep excavation proves that the city already existed by the 6th millennium BC at the latest. And it is clear that Nineveh was a centre of far-reaching importance by at least the mid-3rd millennium BC because its typical pottery, which today we call "Ninevite 5", has been found in a number of ancient cities in northern Iraq and Syria.

Nineveh was the city of the goddess known as Inanna in Sumerian, Ištar PGP in the Assyrian and Babylonian language, and Šawuška in Hurrian and Hittite. She was worshipped in several Near Eastern cities but Ištar-of-Nineveh was considered particularly powerful. In the 14th century BC the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III asked his ally the king of Mittani, who then controlled Nineveh, to let her statue visit him to bestow blessings upon Egypt.

Sennacherib's new city of residence

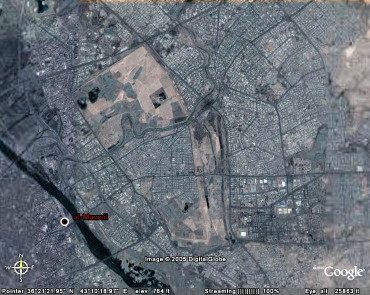

This satellite image shows the ruins of Nineveh amidst the modern city of Mosul. The course of the city walls and the mounds of Kouyunjik and Nebi Yunus (covered by a mosque) on its western side are easy to make out. The southern and northern parts of the city, including Kouyunjik, are archaeological zones but the middle is covered by the modern city. Photo © Google Earth, 2010. View large image.

From the creation of the Middle Assyrian kingdom in the mid-14th century BC onwards, Nineveh was one of the most important cities of Assyria. It was always the centre of an Assyrian province and housed one of the most important garrisons of Assyria's standing army. But it was only under Sennacherib that Nineveh was transformed into the enormous city of 750 hectares that was so praised and condemned in the Bible.

The original city encompassed only the mound of Kouyunjik and its immediate surroundings in the area north of the Khosr River. Sennacherib added the territory of the formerly separate city of Nurrugum, situated on the southern bank of the Khosr River and today known as the mound of Nebi Yunus.

Tradition has it that the mound of Nebi Yunus (meaning "Prophet Jonah" in Arabic) contains the grave of the Biblical prophet Jonah, who is thought to have died in Nineveh; it is the site of an important mosque. According to the Bible, God ordered Jonah, a man from the region of Nazareth, to go to Nineveh to prophesise the immanent doom of that godless metropolis to its inhabitants. Jonah tried to escape his destiny by boarding a ship bound for Spain, as far away from Nineveh as possible. But when a storm arose, the crew blamed the runaway Jonah and threw him overboard. He survived but was swallowed by an enormous fish or whale. Finally accepting his mission after three days' thinking in its belly, Jonah was vomited out again onto dry land. He finally made it to Nineveh, where he walked through the city proclaiming, "In forty days Nineveh shall be destroyed!" Nineveh's inhabitants believed him, so the story goes, and did penance, so that God showed mercy and spared the city – for the time being.

Gates, palaces, temples and gardens

Sennacherib had a fortification wall 12 kilometres long constructed around Nineveh. Access was provided by fifteen gigantic gateways which were fortresses in their own right, with an inner and an outer gate and rooms over two storeys to house the garrisons. When the Babylonian and Median armies attacked Nineveh in 612 much of the fighting took place in and around these gates. During David Stronach's 1989 excavation of the Halzi Gate heaps of skeletons of men and horses fallen in battle came to light.

Sennacherib built a palace on Kouyunjik, which he lavishly adorned, as we know from the excavations that have been conducted in Nineveh since the mid-19th century AD. Sennacherib's numerous building inscriptions also describe the construction of his New Palace PGP in great detail. Because they were composed at various times during the construction of Nineveh they allow us to trace the different stages of the enormous building project in some detail. The king shows himself especially pleased that he used stone from a new and conveniently located quarry and that the royal parks surrounding the palace employed novel ways to irrigate exotic plants such as cotton that none of his predecessors had been able to acquire.

Sennacherib also renovated the old temples of Nineveh and added new ones, such as the Akitu TT House and a shrine for the moon god Sin PGP . This temple is probably where Sennacherib was murdered by two of his sons, according to Eckart Frahm.

Sennacherib's successors continued the royal building works in Nineveh. Esarhaddon's most important project was the construction of the Review Palace PGP on Nebi Yunus. Test excavations have shown that it lies underneath today's mosque, and for that reason it cannot be explored in detail. But we can assume that the architecture of the Review Palace resembled its heavily fortified namesake in Kalhu PGP , which the security-conscious Esarhaddon had adapted from an earlier building.

Assurbanipal renovated several of Sennacherib's buildings on Kouyunjik, among them his palace and the temple of Ištar. But he also contributed a grand structure of his own to Nineveh's architecture, the so-called North Palace PGP . The Garden Party relief is perhaps the most famous piece among its lavish stone decorations and shows the king and queen celebrating victory over Elam PGP in 645 BC.

Water for Nineveh

A block from the collapsed monumental façade of the weir at Hinnis which Sennacherib had constructed to harness the spring waters of the Gomel River for the steady supply of water to Nineveh. The decoration shows king Sennacherib and his divine master Aššur, unusually for Assyrian bas reliefs in full frontal view. Photo by Karen Radner. View large image.

The new metropolis needed an enormous amount of water, not only to irrigate the fabulous royal parks but especially to increase the area which could be farmed. Additional fields, vegetable gardens and fruit groves were all needed to provide food for Nineveh's ever-increasing population. In his inscriptions, Sennacherib proudly claims that he allocated a garden plot to every Ninevite.

To provide the necessary volumes of water, the king embarked on a hydraulic engineering project to bring water into the city directly from the mountain springs north of Nineveh. It was the most ambitious ancient project of its kind. Aqueducts, subterranean canals, dams and reservoirs were built, all to the highest technological standards and often lavishly decorated with reliefs and inscriptions. Over the course of fifteen years, 702-688 BC, Sennacherib's engineers constructed a network of 150 kilometres of canals to transport the water from the mountains straight to Nineveh.

Like every irrigation system, these waterworks needed constant maintenance and repair. So when Nineveh fell to the Babylonian and Median armies in 612 BC the complex quickly ceased to function properly as no-one was financing or organising the regular upkeep that was necessary. This collapse contributed to the rapid abandonment of the city because without artificial irrigation it could not provide a home for its many inhabitants. Nineveh soon became a ghost town.

Further reading

17 Apr 2024Karen Radner

Karen Radner, 'Nineveh, Assyria's capital in the 7th century BC', Knowledge and Power, Higher Education Academy, 2024 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/saao/knpp/essentials/nineveh/]