The Nature of the Transactions

By their content, the texts in the present volume fall into two major types, purchase documents mostly recording the acquisition of landed property and slaves by the central persons, and loan documents mostly recording issues of money, corn, animals and wine by the same persons. Other types of documents are extremely sparsely represented in the corpus and include a few court decisions (nos. 35, 133, 238, 264 and 265) largely relating to economic affair[[24]] and a building contract (no. 21). A bird's-eye view of the types of documents and the quantities in which they are represented in the volume is presented in Table IV.

A mere typological survey, however, can only give a superficial idea of the nature of the Nineveh court transactions. To obtain a more satisfactory picture, it is necessary to take into consideration other matters too, like the quantities of money and property involved in the transactions.

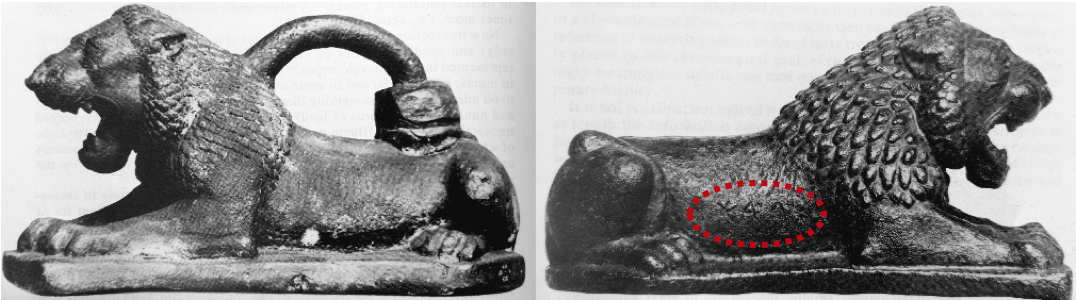

Left: Bronze lion-weight (14.934 kg), inscribed in Aramaic with their weights, 15 royal minas, and marked with a corresponding number of strokes on their flanks. From Nimrud (BM 091220)

Right: Bronze lion-weight (2.865 kg), 3 royal minas,from Nimrud (BM 091226).

The money value of the transactions was mostly expressed in terms of silver minas divided into 60 shekels, more rarely in terms of copper minas and talents.[[25]] While a passage in the inscriptions of Sennacherib makes it likely that coined money already existed,[[26]] the value of a silver mina almost certainly depended on its weight. Two principal varieties of the silver mina, probably related to different weight systems, occur in the texts. The "royal mina," or the "mina of the country," exemplified by a series of inscribed lion-weights from Nimrud dating from the reigns of Shalmaneser V through Sennacherib (see image above), was an almost exact equivant of the modern kilo. The weight of the "Carchemish mina," the other common standard, is unknown, but it cannot have differed much from that of the royal mina.[[27]] The exchange rate between silver and copper appears to have been 1:60, so that a talent of copper (or sixty copper minas) corresponded to one silver mina.[[28]]

To establish exact correspondencies between ancient and modern currencies is of course impossible, but roughly, an Assyrian silver shekel may be said to have equalled about 5 US dollars at its current value and much more in its real purchasing power.[[29]] A silver mina would have been worth sixty times more, i.e., about $300.

Now transactions involving modest sums of money (a few shekels of silver only) and small properties (a few decares of land) are extremely poorly represented in the Nineveh corpus.[[30]] Most of the prices mentioned are defined in minas, not shekels, and in some texts truly large quantities of money (up to 60 minas of silver, something like $18,000)[[31]] and property (entire villages and hundreds of hectares of land)[[32]] change hands. Clearly, the texts record transactions by very afflueut people, and it is interesting to note, in the light of what was said above, that the most affluent of all were the royal charioteers and bodyguards, who easily surpass everybody else in the corpus by the volume of their investments and spending.[[33]]

These nouveaux riches appear to have spent their money mainly in amassing land and slaves all around Assyria.[[34]] Some of them evince a bent for la dolce vita by their obvious zeal to acquire vineyards;[[35]] many of them were active as moneylenders.[[36]] It is interesting to note, however, that not all the loans given by them were meant to bring profit. Other members of the ruling elite could borrow considerable sums of money and other commodities for no interest,[[37]] and the interest rates prescribed in loans of this type in the event of nonpayment could be ridiculously low compared with the rates applying in normal loans of the period.[[38]]

Three loans of wine included in the volume (nos. 181/182, 232 and 233) fall into this category. In each of them the debtor receives a large amount (up to 1,000 litres) of wine, which he is to give back a few months later. No interest is prescribed. Only in the event that the wine is not returned, a penalty will apply: the debtor is to repay the wine in silver according to the market price of Nineveh. This shows that the documents are to be taken as true loans and not, e.g., as retail or wholesale contracts. For if the owner of the wine was interested in simply converting the wine into money, why would the other party not have been required to sell it in Nineveh in the first place, where it obviously would have fetched a better price?

One possible explanation for this type of loan could be that the recipient was a member of the ruling class urgently needing the wine for a particular purpose, e.g. a party for a large number of guests. Buying the wine at a local store in Nineveh would have cost fortunes and was, in fact, unnecessary since the colleague, by virtue of his office, was in control of large quantities of palace wine from which the need could be supplied without any difficulty. By the repayment deadline the debtor would have had time to acquire the quantity of loaned wine cheaply from elsewhere. Should this prove impossible, he would still have lost nothing: the prescribed "penalty" was simply the amount of money he would have had to pay anyway, had he not been able to avail himself of the cheap loan.[[39]]

24 See especially no. 35 concerning burglary into the house of a "central person" and possibly referring to the impalement of the thieves on the site in accordance with Codex Hammurabi. It is possible, though, that the verb zaqāpu in this text does not have the meaning "impale," in which case the crucial sentence would have to be rendered "the thieves who attacked the house of PN" in accordance with the normal NA meaning of the verb.

25 Copper appears as a means of payment quite frequently in the early texts of the volume (see nos. 2, 3, 6, 7, 15, 19, 21, 22, 29, 32) and is still often encountered in texts from the reign of Sennacherib (17 examples). In later texts, however, it occurs very rarely (only in nos, 214, 264f and 289f.

26 "I executed with superior artistry cast bronzework (for the figures of various large animals), and upon an inspiration from the god, built clay molds, poured bronze into each, and made the figures of each of them as perfect as minted half-shekel pieces (pitiq 1/2 GÍN.TA.ÀM)," Luckenbill Senn. 109 ii 16, also ibid. 123: 9 (editor's note: cf. however RINAP 3 edition [http://oracc.org/rinap/Q003491/], especially footnote number 43).

27 There is no noticeable difference in prices of real estate and humans stated in terms of royal and Carchemish minas; cf., e.g., no. 138 vs. nos. 34, 45, 257, 305f, 343f and 346f, for slaves costing 1 royal and 1 Carchemish mina respectively, and nos. 85 and 130 vs. nos. 57 and 111 for slaves costing half a royal or Carchemish mina respectively. In this light, one would feel tempted to regard the duck-weights found in various Assyrian sites as specimens of the Carchcmish standard, but various considerations (not least the lion-figure) make this improbable.

28 "See, e.g., no. 152 recording the purchase of a woman for a talent of copper, or nos. 56 and 61 referring to men sold or released from bondage for 30 minas of copper, and cf. the previous footnote.

29 The 'rate' is based on recent world market prices of silver, which of course fluctuate considerably depending on the strength of the currency but appear to have remained relatively stable in real terms over the past few years (1985-1990) at least. The matter requires furher study, but the suggested 'value' appears in any case to fit the NA evidence tolerably well, cf., e.g., ND 02312 (lraq 23 pl. 10) referring to garments and coats costing 4 1/2 and 2 1/3 shekels, and no. 241 of the present volume stating 3 minas of silver as the price of a camel.

30 See nos. 115, 161 (purchases of land for 5 and 4 shekels of silver respectively) and 189 (loan of 5 shekels of silver).

31 See no. 253, recording the purchase of 60 hectares of land by Issar-duri, scribe of the queen mother.

32 Cf. nos. 336 (580 hectares), 287 (village of Bahaya, 500 ha) and 245 (200 ha).

33 The 'top spenders' in the volume are Šumma-ilani, chariot driver of the royal corps (cf. nos. 34, 39, 42, 50f), Remanni-Adad, Assurbanipal's charioteer (cf. nos. 311, 318, 323f, 326, 329, 335, and 343f), Nabû-šumu-iškun, Sennacherib's charioteer (cf. no. 57), Mannu-ki-Arbail, cohort commander (cf. nos. 202, also 269?), Zazî, royal eunuch (no. 26), Atar-il, eunuch of the crown prince of Babylon (no. 287), Aplaya, 'third man' of Arda-Mullissi (no. 107), and the unidentified Dannaya (no. 248), Silim-Aššur (no. 234) and Baltaya (no. 130), all with investments and purchases ranging between 30 and 3 royal and Carchemish minas. It is likely that the name of the central person in no. 196, recording a purchase price as high as 30 Carchemish minas, is to be restored as [Šumma-ila]ni.

34 For purchases of landed property, see especially nos. 10-15 (Inurta-ilaʾi), 37, 42 and 51f (Šumma-ilani), 101f and 105 (Aplaya), 201, 202, 204, 207, 209-211, 213 and 217 (Mannu-ki-Arbail) and 304, 311, 314-316, 320-322, 325f, 328-340 (Remanni-Adad); for purchases of slaves, note especially nos. 1-9 (Mušallim-Issar), 34, 38-41,45, 48f and 52-56 (Šumma-ilani), 57f (Nabû-šumu-iškun), 82, 85-89, 92 and 94 (harem governesses), 103 and 106 (Aplaya), 109-112 (Seʾ-madi, Village Manager of the Crown Prince), 227-229 (Silim-Aššur), 239, 244 and 246 (Dannaya), as well as 297f, 300f, 305f, 309f. 312f, 319, and 341-348 (Remanni-Adad).

35 Particularly Šumma-ilani (see nos. 37 and 50), Mannu-ki-Arbail (nos. 201f) and Remanni-Adad (nos. 314, 326, 329-332, 334 and 336).

36 E.g., Zazî, Šumma-ilani, Addati. Aplaya, Munnu-ki-Arbail, Silim-Aššur, Dannuya, Remanni-Adad (money) and Bahianu (money and corn).

37 For loans with no interest in the present volume see, e.g., nos. 97, 143, 167, 180, 273, 318 and 234. In no. 318, the deputy governor of Arrapha receives from Remanni-Adad as much as 10 minas of Carchemish for no interest.

38 25% in nos. 167 and 318; for the normal interest and penalty rates see the evidence tabulated in S. Ponchia, "Neo-Assyrian corn loans: Preliminary notes," SAAB 4 (1990), 38ff.

39 This interpretation is of course largely speculation but supported by a consideration of the other loans with no interest in the present volume. Unfortunately it is not possible to pursue the matter in more depth in this context.

Simo Parpola

Simo Parpola, 'The Nature of the Transactions', Legal Transactions of the Royal Court of Nineveh, Part I: Tiglath-Pileser III through Esarhaddon, SAA 6. Original publication: Helsinki, Helsinki University Press, 1991; online contents: SAAo/SAA06 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2020 [http://oracc.org/saao/saa06/natureoftheninevehlegalarchive/natureofthetransactions/]