Application of medicaments

Ranging from essentially everyday operations like blowing, dripping or pouring dried and crushed substances into the ears and eyes, to more complex therapies that included bandages, salves, poultices, pills, healing potions, tampons, suppositories, enemas, lotions and fumigation, therapeutic texts record an extensive selection of methods for applying medicaments. While the number of such methods is indeed considerable, it seems that in any given context only a couple of them feature prominently, while others occur only a few times or missing completely.

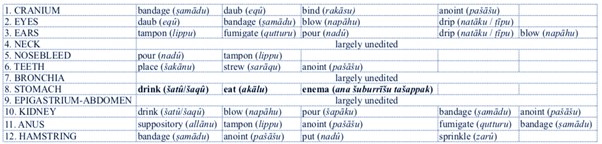

The existence of characteristic forms of medications in Mesopotamian medicine is clearly inferable from the Nineveh Medical Encyclopaedia. Interestingly, in the anatomical part of this series, the choice of appropriate healing methods appears to be dependent on the body part rather than the actual disease that the medication was meant to treat. In the following selective list, the first entry in each line refers to the form of medication which features most prominently in the corresponding treatise. This is followed by other healing methods that are still well attested but less common than the most characteristic form of medication.

In order to cure diseases affecting the head, practitioners mainly used bandages, while other types of therapy like daubing or anointing the infected area with a salve also played an important role but not as the most characteristic form of medication.

You take frond from gišimmaru ("date palm") which sways even when there is no wind, you dry it in the open air, you crush (and) sift it, you knead it in juice from kasû ("tamarind") (and) you bandage him with it. (Cranium 2, BAM 482+ i 21-22)

You dry (and) pound (a plant with) the name murru ("myrrh"), you mix it in water (and) you continuously anoint his head with it, (then) he should smear off (the anointment) using a cloth of date palm fibre (and) once he cleaned himself with it, he should burn it. You mix imhur-līm ("faces a thousand" plant) in oil from erēnu ("cedar") (and) you continuously anoint him (with the mixture). (Cranium 4, CT 23 50 i 5-6)

Bandages were important in treating eye diseases. However, in this context, daubing seems to be the most characteristic form of therapy, while other less frequent treatments included dripping and blowing healing substances directly into the eyes with the help of a bronze tube or a reed straw.

You pound one shekel of rikibti arkabi ("bat guano"), half a shekel of šammu peṣû ("white plant") (and) a fourth of a shekel of emesallu (a kind of salt) in dišpu ("syrup") from the mountains (and) oil (and) you daub his eyes (with the mixture). (Eyes 3, BAM 516 i 6'-7')

You pound urnû (a kind of mint) (and) šammu peṣû ("white plant") (and) you blow them into his eyes using a bronze tube. (Eyes 1, BAM 510+ ii 25')

The latter procedure also highlights an important aspect of Mesopotamian medicine, namely, to search for ways to be able to introduce medicaments directly into the infected part of the human body. According to the treatise on ear diseases, for instance, practitioners mostly prepared tampons containing all sorts of healing substances and placed them into the earholes, so that the medicament could directly reach the diseased area. Fumigation was another way of achieving this goal.

You pound ešmekku (a stone) [. . .] murru ("myrrh") (and) urnû (a kind of mint) together, you mix them in blood from erēnu ("cedar"), you recite the incantation three times over (the mixture), you wrap it in a tuft of wool (and) you place it inside his ears. (Ears, BAM 503+ ii 14-15)

You fumigate the inside of his ears with qaran ayyali ("stag horn"), gabû ("alum"), nīnû (a kind of mint), sahlû ("cress"), imbû tâmti ("algae"), kibritu (a kind of sulphur) (and) eṣemti amēlūti ("human bone") using coal from ašāgu ("acacia"). (Ears, BAM 503+ i 36'-37')

Geared toward the specific needs of the infected area, the treatise concerned with dentistry mainly contains descriptions of healing procedures that involved placing or strewing the processed healing substances over the sick or aching teeth.

You smash humbabītu (a kind of lizard), you wrap it in a tuft of wool, you sprinkle it with oil (and) you place it inside his sick tooth (. . .) you pound zību ("black cumin") (and) you place it over his tooth (. . .) you pound atā'išu (a plant) (and) you smear it over his tooth. (Teeth 1, BAM 538+ ii 49'-51')

Healing potions were one of the most classical methods of applying medicine internally, and they feature mainly in the context of diseases affecting the inside of the body. In the treatise on the digestive and gastro-intestinal tract, healing potions represent the characteristic form of medication, alongside another important method of internal application -- enemas.

In order to heal him, kukru (an aromatic), burāšu (a kind of juniper) (and) ṣumlalû (an aromatic) -- you take these three drugs when they are fresh, you dry (and) pound them, you have him drink them in strong wine on an empty stomach, he will void, and then you bandage his epigastrium (and) his belly. He eats warm (food), he drinks warm (drinks), on the third day you purge him, and then he will recover. (Stomach 3, BAM 578+ i 30-32)

You pound karān šēlebi ("fox-vine"), he drinks it in beer, (and then) he eats fatty meat. He drinks burāšu (a kind of juniper) (and) ṭūru ("opopanax") in beer, (then) you heat up (these ingredients) in beer (and) you pour (tašappak) them into his anus. (Stomach 4, AMT 23/5+ i 16')

Healing diseases of the renal-urinary tract represents another area of Mesopotamian medicine where potions featured most prominently. In this context, however, practitioners also tried to reach the infected part of the body by pouring and blowing powdered substances through a reed straw or a bronze tube into the urethra.

You heat up resin from baluhhu (an aromatic) (and) pressed oil, you filter them (and) you blow them into his urethra using a bronze tube. (Kidney 2?, BAM 7 2 i 22)

You pound šammu peṣû ("white plant"), you mix it in oil (and) you blow (the mixture) into his urethra using a bronze tube. (Kidney 2?, BAM 7 2 i 23)

In the case of rectal diseases, the infected area can most effectively be reached with the help of suppositories. Not surprisingly, practitioners in Mesopotamia also preferred this method when it came to treating problems of the colon and rectum. The process of preparing suppositories started by crushing and sifting the active ingredients. Then, the semi-liquid carrier followed, which was usually tallow or suet, but sometimes also wax, honey or the resin of the balu??u aromatic. Sometimes the carrier substance was heated, although a short reference to mixing it with the crushed drugs is much more common in the texts. After the suppository was put together, the texts may also instruct to sprinkle it with another liquid like cypress oil that presumably served as a lubricant. The concluding remark in medical recipes usually is "you insert (the suppository) into his anus" (ana šuburrīšu tašakkan).

In order to heal him, you pound in equal amounts nīnû (a kind of mint), burāšu (a kind of juniper), (kanaktu (an aromatic), kukru (an aromatic) (and) šammi balāṭi ("plant of life"), you mix them in tallow, you make a suppository, you sprinkle it with oil from šurmēnu ("cypress"), you insert it into his anus, and then he will get better. (Anus 1, BAM 7 22 i 1-4)

Krisztian Simko

Krisztian Simko, 'Application of medicaments', The Nineveh Medical Project, The Nineveh Medical Project, Department of the Middle East, The British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG, 2022 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/asbp/NinMed/medicaltechniques/applicationofmedicaments/]