Investigating the materiality of inscriptions at the British Museum

Since its earliest days, the study of cuneiform inscriptions has relied on drawings of the ancient texts, known as hand-copies TT . However, Assyriologists TT like Jonathan Taylor at the British Museum are using exciting new approaches that focus on cuneiform TT tablets TT as physical objects in their own right, enabling them to reconstruct the way these tablets were written. Here Jon describes his working methods.

Traditional approaches to cuneiform

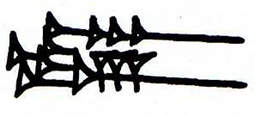

Traditional academic study of cuneiform texts has separated the texts from the objects on which they were written. Assyriologists have made line drawings of the inscriptions, called hand-copies TT , for practical reasons of publishing in printed books and journals. A hand-copy reduces the inherently three-dimensional cuneiform script to a two-dimensional representation. It also removes information that the copyist either did not notice or did not feel was significant. The drawings are then further abstracted by converting them into Latin characters. So for example, this cuneiform sign:

is written LUGAL (meaning "king").

When more than one example of a text exists – such as literary texts or royal inscriptions – a single, artificial, "composite text" TT is created. This merges all examples together, making something that never really existed in antiquity, but is nevertheless useful for modern Assyriologists' purposes. Composites are especially useful when the source documents are broken, which is most of the time.

This approach is practical and certainly has benefits. It makes cuneiform relatively easy to communicate to other academics and to work with, particularly with the help of computers to manage large datasets. But it comes at a cost. It is often easy to tell a lot about a text from something as simple as the size and shape of the object on which it is written. This information is hard to communicate in drawings, and has often been ignored altogether. Even more importantly, inscriptions are hand-made. Everything from the materials used, the processing and manufacturing techniques, through the formatting habits, to the handwriting and spelling all bear the mark of the person who created the inscription.

Materiality of the text

The handwritten nature of cuneiform writing presents modern researchers with a rich supply of information about how ancient scribes TT worked. Academics in other fields routinely examine inked inscriptions to discover what kind of writing implement was used and how the scribe made letters from individual strokes. I have been using these new techniques in order to do the same with cuneiform writing. Photographs reveal a great deal but even better is to examine the object itself.

Wedge order

On the left below is a hand-copy of the cuneiform sign PA, taken from an inscription from Nimrud. On the right is a photograph of that same sign on the clay tablet:

It is possible to extract more information from the photo than from the hand drawing. Sometimes when writing cuneiform on clay, the act of impressing the stylus TT to make an individual wedge TT distorts the impression left in a previous wedge. A small amount of clay can be pushed into the impression TT of the earlier wedge, or the long, straight section (known as the "tail") of the wedge can be bent. This allows us to tell the order in which the scribe made each wedge in the signs. Here the vertical wedge has been written before the two horizontal wedges.

Here is another sign from a cuneiform inscription from Nimrud. On the left is a hand-copy of the GIŠ sign, which is very similar to the PA sign above. On the right is a photograph of the same sign on the clay tablet:

In this example the scribe wrote the two horizontal wedges first, then the vertical. Looking at many signs from many tablets, it is possible to determine the principles governing how cuneiform was written. Some of these are common to cuneiform as written in different times and places, others are more restricted. Similar ordering principles are still used today in East Asian writing - Chinese, Japanese, Korean. They help the writer learn the characters, and how to form them properly.

Through features such as wedge order, as well as other writing or formatting habits, and clues from the clay of the tablet itself, we can distinguish the work of scribes educated at different times and in different places. It may even help to differentiate individual scribes working at the same time in the same place. This can be important evidence in our attempts to understand the context of documents. Was more than one scribe working at the same time in a given bureau? When does scribe A's work begin and end? How does this relate to anything else we may know about that scribe?

The reed stylus

Looking again at the two photos, we can see something else that is lost in the hand drawings. The stylus these scribes were using was made from reed. This is visible in the texture of the surfaces of the wedges themselves. Each wedge is a more or less pyramid-shaped hole in the clay. The left end of each wedge is marked with lines. The top end looks spotty. And the right end looks smooth. This is a result of the way the stylus was cut from the reed. The lines are the impression left by the fibres within the reed, exposed when the scribe cut the stylus. The spots are the ends of these same fibres. The smooth surface of the right end of the wedge is the impression of the uncut, outer surface of the reed. So while other materials could have been used to make a stylus, in many cases it is clear that reed was the preferred material.

Content last modified: 18 Dec 2019.

Further reading

- Taylor, J., 2011. "Tablets as artefacts, scribes as artisans", in K. Radner and E. Robson (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 5–31.

Jonathan Taylor

Jonathan Taylor, 'Investigating the materiality of inscriptions at the British Museum', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/modernnimrud/atthemuseum/materialityofinscriptions/]