Writing cuneiform on clay

Cuneiform TT is designed to be written on clay. The wedge-shaped impressions that give cuneiform its modern name are made by pressing a stylus TT into the surface of a moist clay tablet TT . The stylus is then lifted back up ready to make the next impression, rather than dragged across the surface as we would use a pen. Some tablets were enclosed within a clay envelope. And tablets or envelopes were sometimes stamped or sealed. There are strong connections between a language, the writing system in which it is written, the medium on which it is usually written and the technique of writing. The Sumerian and Akkadian languages were typically written in cuneiform script on clay but were also sometimes written on other media.

Object shapes and sizes

[/nimrud/images/langscripts/BM90976-40cm.jpg]

[/nimrud/images/langscripts/BM90976-40cm.jpg]Image 1: This clay hand TT lists the titles of king Assurnasirpal II. Its first line says it is from "the palace", meaning the Northwest Palace (1). BM 90976. View large image (193KB). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Most cuneiform inscriptions were written on clay tablets. Scribes used different shapes and sizes of tablet for different purposes, but made most of them to fit comfortably in the hand. The Succession Treaties of Esarhaddon PGP are written on unusually large and thick tablets. We can identify various types of clay, some containing stones or shells, others with very few inclusions TT . This is similar to our use of different sizes and qualities of paper for newspapers, letters and post-it notes.

Image 2: Left: a typical cylinder of king Sargon II PGP , with flattened faces. BM 108775. This example is from Dur-Šarruken PGP (modern Khorsabad), but Sargon deposited similar examples in Kalhu. Right: a typical cylinder of Esarhaddon PGP from Kalhu, narrower and fully rounded (translation online: RINAP 4: 77). British Museum BM 131129 (ND1126). View large image. Image: Jon Taylor for the Nimrud Project CC-BY-SA 3.0.

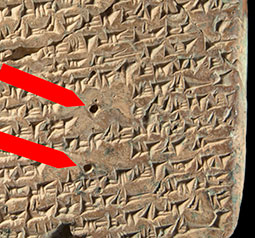

Clay could also be formed into other shapes for special purposes. Assyrian kings of the first millennium BC had their inscriptions written on a variety of objects: tablets, cones, bricks, prisms and cylinders. They discussed the exact text of each inscription with the scribe, and carefully chose the objects thems as well. Two popular types of object chosen to carry royal inscriptions were prisms and cylinders. The size and shape of these varies from one ruler to the next (Image 2). We even find royal inscriptions on architectural fittings in the shape of hands TT (Image 1).

Image 3: Some typical tablet shapes for the various types of text found at Nimrud. View large image. Image: Jon Taylor for the Nimrud Project CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Scribes also chose certain shapes and sizes for each of the different types of text from daily life. They sometimes wrote loans of barley on triangular dockets TT . But sales of slaves or land (known now as "conveyances" TT ) are characterised by their portrait format TT and band of seal TT impressions TT across the upper obverse TT . The more ephemeral contracts (for things such as loans) meanwhile are smaller, landscape format TT tablets, with envelopes. The scribe sealed the envelope but not the table. A typical letter would be portrait format, but thinner than a conveyance and not sealed. Scholarly tablets are often written in portrait orientation, in one or two columns. Image 3 shows some common tablet types from Nimrud.

Working with clay

Image 4: Many stone inclusions TT are present in the clay of this tablet from Kalhu. The tablet itself contains an 8th century BC letter about purchasing horses (translation online: SAA 19: 168). British Museum ND 2627. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Clay for making tablets was readily available from rivers. So too were reeds for making a stylus. The clay for tablets could first be processed to remove stones and plant matter. This did not always happen, however, and many tablets contain such inclusions TT (Image 4). Indeed, tablets from Nimrud contain inclusions much more often than those from Nineveh PGP , for example.

Assyriologist TT Henry Saggs tested the clays of tablets from Nimrud (2). He found that tablets originally from Babylonia PGP contained a higher level of lime TT than their Assyrian counterparts. This made them softer, and less likely to suffer cracking, but more susceptible to damage from salts coming to the surface and breaking off text as they crystallised.

Image 5: Scholarly tablet of tamītu prayers (CTN 4 62), with visible "firing holes". Despite their name, the exact function of these holes is not known. British Museum ND 4401. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Most tablets were not fired in antiquity. Left to dry in the air (preferably not in the sun, which dries them too quickly), tablets become hard enough to withstand normal handling and storage. This means that they could potentially be recycled by soaking the clay in water, although in many cases old tablets were simply discarded. Tablets intended to survive for very long periods could be fired. Such tablets sometimes contain what Assyriologists call "firing holes", the actual function of which was probably not to assist in the firing process, however (Image 5).

Tablet making

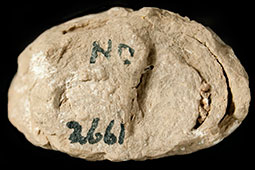

Image 6: End view of a tablet, showing visible individual layers where the sheet of clay has been rolled into a tablet shape. This 8th century BC tablet is inscribed with a letter to the king about mules for a postal service (translation online: SAA 19: 141). British Museum ND 2661. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Image 7: End view of a tablet, showing a skin of fine clay wrapped around a core of rougher clay. This 8th century BC tablet is a letter reporting on an Ionian PGP raid on a western province TT of Assyria (translation online: SAA 19: 25). British Museum ND 2370. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Many tablets survive only in broken condition. While this obviously means that we have lost some of the text, it does sometimes allow us to see how the tablet was made. Often we can see that the scribe TT had rolled a sheet of clay into the tablet shape (Image 6). Another technique saw a skin of fine clay wrapped around a core of rougher clay (Image 7).

Sealing

People had long used seals to confirm identity or indicate authority. The Succession Treaties of Esarhaddon are sealed with no fewer than three cylinder seals. During the Neo-Assyrian TT period, old-fashioned cylinder seals gave way to stamp seals. Instead of being rolled across the surface, a stamp seal was simply impressed into the clay. Sometimes people kept an old cylinder seal, and used it as though it were a stamp seal.

Another method of sealing was to use a fingernail. One example of a tablet sealed using this method is a legal document bearing the impressions of men's fingernails "instead of their seal", to certify that debts owed to them have been repaid. Some historians have suggested that some fingernail impressions were made with a special tool.

Enveloping

There was a very long tradition in Mesopotamia of enclosing texts within protective envelopes. Like a modern envelope, the Assyrian type was made from a folded sheet (although in this case made of clay rather than paper). In the case of a letter, the scribe wrote the name of both sender and recipient on the envelope, together with a short greeting and a seal impression to confirm the sender's identity. Few envelopes survive, because the act of opening them meant breaking them; the broken pieces would then be discarded.

Stylus

The Akkadian word for stylus is qān ṭuppi, which literally means "tablet reed". Reed was a natural and very suitable material for a stylus. We can sometimes see traces of the fibres of the reed in the wedges TT of cuneiform. Wood, bone and other materials could also be used. No original Assyrian styluses survive.

Storage

Mesopotamian scribes stored their tablets in jars, bags, or on shelves. Max Mallowan, who excavated in Nimrud in the 1950s, suggested that the feature in archive room ZT 4 of the Northwest Palace should be interpreted as a filing cabinet for tablets (Image 8).

Content last modified: 18 Dec 2019.

References

- Grayson, A.K., 1991. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC: I (1114-859 BC) (Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Periods. Volume 2), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 373-4, A.0.101.123. (Find in text ^)

- Saggs, H.W.F., 2001. The Nimrud Letters, 1952 (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 5), London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq (free PDF from BISI, 156 MB), p. 2. (Find in text ^)

Further reading

- Cartwright, C. and J. Taylor, 2011. "The making and re-making of clay tablets", Scienze dell'antichità 17, pp. 297-324.

- .

- Parker, B., 1955. "Excavations at Nimrud, 1949-53: seals and seal impressions", Iraq 17, pp. 93-125 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers).

- Radner, K., 1995. "Format and content in Neo-Assyrian texts", in R. Mattila (ed.), Nineveh, 612 BC: The Glory and Fall of the Assyrian Empire. Catalogue of the 10th Anniversary Exhibition of the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, pp. 63-78 (free PDF from Knowledge and Power, 3.1 MB).

- Taylor, J., 2011. "Tablets as artefacts, scribes as artisans", in K. Radner and E. Robson (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 5–31.

- Saggs, H.W.F., 2001. The Nimrud Letters, 1952 (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 5), London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq (free PDF from BISI, 156 MB).

Jonathan Taylor

Jonathan Taylor, 'Writing cuneiform on clay', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thewritings/cuneiformonclay/]