Legal documents

Among the thousands of tablets TT excavated from the cities of ancient Assyria are numerous documents which record legal transactions. Since no collections of laws are known from the Neo-Assyrian TT period, these texts give us a valuable insight into aspects of the Assyrian legal system. They also provide glimpses into Assyrian lives, albeit only those of a fairly narrow section of society.

Charioteers, royal bodyguards... and a sheep rustler

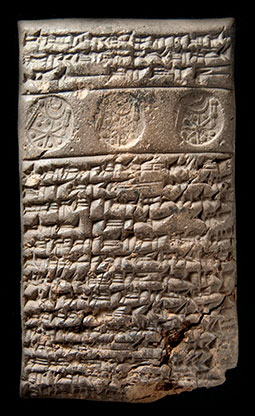

Image 1: Cuneiform tablet from Nimrud, recording the sale of a slave woman named Arbela-lamur ("May I see Arbela PGP !"). An officer in the crown prince TT 's retinue has certified the sale by impressing his stamp seal on to the tablet. The tablet dates from the reign of king Assurbanipal PGP (1), (2). ND 2325. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Most of the documents from royal archives belonged to high-ranking court officials and holders of military posts, such as the royal charioteers and commanders of the royal bodyguard who feature prominently in the Nineveh PGP archives. This may at first glance appear rather unusual until we consider the unique position of charioteers and bodyguards. Their unfettered access to the king put them in a position of great power, so it was vital to secure their loyalty. Lavish gifts were one way to do this, and their numerous transactions were a natural reflection of their wealth. At the same time, requiring them to share their business dealings with the palace allowed king to make sure that these individuals did not get so rich and powerful as to become a threat to him.

The vast majority of legal texts record private transactions. Other types of document, such as court decisions, are also represented, but they are much less common. Collections of laws - or even references to them - are noticeably absent. Most of the legal documents from Assyria deal with purchases of property, particularly of land and people, and with loans or other debt obligations. Purchases of people did not necessarily concern only slaves. Women could be sold into marriage (e.g. SAA 14: 161, which records a woman being sold by her father and brother; Image 1), and children into adoption (e.g. SAA 14: 442).

Image 2: A row of fingernail impression 'signatures' runs in a horizontal row across the top of this tablet from Nimrud, sealing TT the document as substitutes for personal seals. It records Bel-tarṣi-ilumma PGP paying off a huge debt ("2 talents, 20 minas of bronze") for someone named Sabiri. From Room 6 of the Governor's Palace, 793 BC (3). ND 211. View large image on British Museum website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Loans or debt notes usually involved silver TT and corn, but wine, birds, cattle, camels and people are also recorded. Less common types of transactions include receipts and records of court proceedings, which address a variety of matters ranging from adoption (SAA 14: 450) and property disputes to murder and theft (SAA 6: 264, a judgement against one Hani who had raided sheep belonging to the crown prince TT and killed a shepherd in the process; SAA 14: 104).

Image 3: Clay tablet (bottom) and its envelope (top). This loan document from 636* TT BC was excavated from Room 19 of Town Wall house 57, Nimrud (4). ND 3445. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Power in the royal harem

The legal corpus from Nineveh includes a number of tablets recording transactions by women connected to the harem TT (the women's quarters of the palace). From the tablets it is clear that these women enjoyed considerable wealth and influence. It seems that palace women, including concubines, were as free to engage in business outside the court and the city as other members of the palace elite. Just like male courtiers, they bought and sold property, and made loans of money and livestock (SAA 6: 81, 84, 97).

This freedom was not limited to the palace of women of Nineveh: a tablet from Assur PGP shows that if a man failed to repay a debt owed to a woman, the woman was entitled to keep him as a debt slave. There is no evidence that any transactions were taboo for women, nor that there was a social stigma attached to men transacting with women. Married women did not automatically have to defer to their husbands in property matters: a tablet from Nineveh lists Amat-Su'la, "wife of Bel-duri, shield-bearing 'third man'" as part-owner of a house (SAA 6: 142).

The medium and the message

Image 4: A triangular clay docket TT from the royal citadel in Nineveh PGP , c. 670 BC. It records the pledge of a child as security for a loan of silver. The docket probably originally secured a roll of leather inscribed with the terms of the pledge in Aramaic. This particular docket is also inscribed in Aramaic, but dockets commonly contained an Akkadian TT language inscription in cuneiform TT script. BM 1881,0204.148. View large image on British Museum website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Legal transactions were recorded either on clay tablets (Akkadian ṭuppu, dannutu or egirtu) or on rolls of leather (sometimes anachronistically translated as parchment TT ). Only the tablets, however, have survived the passage of millennia. Wooden wax-covered writing boards (le'ȗ) do not seem to have been used for this purpose, presumably because they were too easy to rewrite. The type of transaction directly determined the physical appearance of the document used to record it.

Purchase documents were written on a single portrait format TT (taller than wide) tablet (Image 1). Loans, on the other hand, were recorded on tablets which were landscape format TT (wider than tall) (Image 2). In the 7th century BC loan documents also came to be enclosed in clay envelopes (Image 3). Once the tablet was put inside, the envelope was sealed TT and inscribed with a duplicate of the text on the tablet. The addition of an envelope protected the tablet from damage, both accidental or deliberate. It also provided an extra layer of security for the parties: in the event of a dispute, they could break open the envelope and so settle any argument about the terms.

Documents recording debts of corn (corn dockets TT ) took a very different form. They consisted of a triangular piece of clay which was moulded around a piece of string. The docket TT and string were probably used to secure a roll of leather, though no such scrolls have survived. The terms of the debt were inscribed on the clay docket, which was then sealed by the debtor. The docket acted as a sort of substitute envelope: only by breaking the docket could the parchment be unrolled. The clay docket was usually inscribed with cuneiform script in the Akkadian TT language but Aramaic exemplars are also known, as are dockets documenting transactions other than corn debts (Image 4). The parchment, on the other hand, must always have been written in Aramaic. The fact that traditional cuneiform and the relatively new alphabetic script were used side by side illustrates the multilingual nature of the late Neo-Assyrian empire.

The practice for other types of documents was less standardised, no doubt because they were much less common. Receipts were usually written on "horizontal" TT tablets which were impressed with seals. Court proceedings tended to follow the same format, but sealings seem to have been optional.

Witnesses, seals and fingernails

The Assyrians used two methods to authenticate legal tablets. The first involved the use of a seal to confirm the identity of the seller (in the case of property purchases) or the borrower (in the case of loans). The seller or debtor would impress his (or her) seal TT on to the tablet in front of witnesses. Those who did not own a seal could impress a fingernail (ṣupru) instead (Image 5). This was a relatively common practice in the 8th and early 7th century, and was even reflected in the wording of the tablet. A standard formula recorded that "Instead of their seals they impressed their fingernails". As stamp seals became more widely used in the 7th century BC, fingernail impressions TT on legal documents gradually disappeared.

The sealing of the tablet (or the marking of a fingernail) was carried out before witnesses (šībūti) whose names were listed after the operative part of the document, sometimes with a brief description of who they were. The scribe TT responsible for drawing up the tablet was usually named as the final witness, and labelled as such (e.g. "Witness Šaulanu, scribe, keeper of the tablet" (SAA 6: 17)). The tablet was then dated using the eponym TT dating system. There are isolated instances of tablets which invoke non-human witnesses, such as a document in which the king's statue and Šamaš PGP , the god of justice, lead the list of witnesses. However, these are very rare.

The function of witnesses was two-fold. They guaranteed that the document had been properly sealed, but their presence also ensured that the transaction was carried out in accordance with the parties' wishes. If there was a disagreement, the testimony of witnesses was given even more weight than the tablet itself. The fact that they might be called on to testify meant that witnesses had to be local. This explains why witnesses to transfers of land were often the property's neighbours. In many cases, the parties to the transaction also brought along their own witnesses.

Where were they found?

The Neo-Assyrian legal corpus consists of some 2,000 documents uncovered at about 30 sites within the empire, 9 of them in the Assyrian heartland. The rest come from territories to the west, in what is now Syria, Turkey and Israel. The sites in Assyria proper include the major urban centres of Assur PGP , Kalhu, Dur-Šarruken PGP and Nineveh PGP , all of which at some point served as royal capitals.

The legal corpus includes documents from both private and royal archives. Surviving private archives come mainly from residential buildings in the city of Assur, but some have also been uncovered in Assyria's provinces TT . However, the largest collection of legal texts comes from the palaces and administrative buildings of royal capitals. These include the governor's residence and Fort Shalmaneser in Kalhu, and particularly the palace mound at Kuyunjik PGP in Nineveh: this was the site of the royal palaces and administrative buildings in which most of the legal documents appear to have been found. Unfortunately we know little of their exact provenance, and so it is virtually impossible to reconstruct the original state of the archives. The Nineveh corpus covers a period from the reign of Tiglath-pileser III PGP in the mid-eigth century to the destruction of the city in 612 BC.

Content last modified: 18 Dec 2019.

References

- Parker, B., 1954. "The Nimrud tablets, 1952: business documents", Iraq 16, pp. 29-58 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), p. 42. (Find in text ^)

- Parker, B., 1955. "Excavations at Nimrud, 1949-53: seals and seal impressions", Iraq 17, pp. 93-125 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. 96, plate XXIV, no. 1. (Find in text ^)

- Postgate, J.N., 1973. The Governor's Palace Archive (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 2), London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq (free PDF from BISI, 175 MB), p. 121. (Find in text ^)

- Wiseman, D.J. 1953. "The Nimrud tablets, 1953", Iraq 15, pp. 135-160 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), p. 143. (Find in text ^)

Further reading

- Postgate, J.N., 1976. Fifty Neo-Assyrian Legal Documents, London: Aris & Phillips Ltd.

- Kwasman, T. and S. Parpola, 1991. Legal Transactions of the Royal Court of Nineveh, Part I: Tiglath-pileser III through Esarhaddon (State Archives of Assyria VI), Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

- Mattila, R., 2002. Legal Transactions of the Royal Court of Nineveh, Part II: Assurbanipal through Sin-šarru-iškun (State Archives of Assyria XIV), Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

- Radner, K., 2003. "Neo-Assyrian period", in R. Westbrook (ed.), A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law (Handbuch der Orientalistik 72), Leiden: Brill, pp. 883-910 (free PDF, 5.2 MB).

Silvie Zamazalová

Silvie Zamazalová, 'Legal documents', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thewritings/legaldocuments/]