The Governor's Palace

The Governor's Palace is a modern designation given to a beautifully decorated building which lay to the northwest of Nabu's temple, Ezida. The site proved to be the location of an important collection of cuneiform tablets, including texts relating to the activities of several governors which gave the building its name.

A governor's residence?

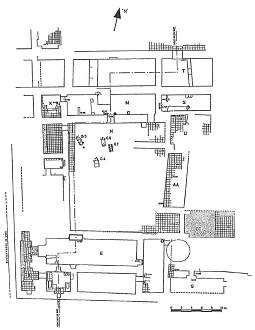

Image 1: Plan of the excavated areas of the Governor's Palace, showing the rooms mentioned in the text. (1). View large image. Photo: BSAI/BISI.

The sumptuously decorated palace was located near the central part of Kalhu's citadel TT mound, next to the important temple of the god Nabu. Only a part of the structure has been uncovered so far. This area measures approximately 50 x 50 metres and seems to have lain at the heart of a much larger complex. A plan of the excavated areas (Image 1) gives some idea of the building's overall layout and function. Like most Assyrian palaces, it was built around a large central courtyard. This was flanked in the north and south by a number of large audience chambers which were used for official business. The palace walls were lavishly painted with geometric patterns in black, white, red and brilliant cobalt blue. The use of blue paint was particularly prominent in the northern suites of the palace, where such a vibrant colour must have had a striking effect on visitors. The palace also featured a well appointed ablution room, or ritual TT bathroom, which was located in the south-west corner, next to room B. The room had been waterproofed using bitumen TT (a component of petroleum collected from springs) and included a carefully-constructed drainage system. The walls were decorated with black and white frescoes of concentric rosettes or circles (Image 2).

Image 2: Detail of the ablution room in the southwest corner of the Governor's Palace. Remains of geometric paintings are visible on the walls, made using black and white paint. Striking red and cobalt blue colours were also used in other areas of the palace (2). View large image. Photo: BSAI/BISI.

The mud-brick palace was probably built by king Shalmaneser III (r. 858-824 BC), as bricks inscribed with his name have been found embedded in the building's pavements. However, it has been suggested that these bricks were left over from Shalmaneser's construction of the ziggurat and may have been re-used by his grandson, Adad-nerari III PGP (r. 810-783 BC), to build the Governor's Palace.

The Governor TT 's Palace was excavated under the direction of Sir Max Mallowan PGP during his first two seasons TT at Nimrud (1949 and 1950). It was given the initial designation of the "1949 building", but this was quickly replaced with the more imaginative "Governor's Palace" when cuneiform tablets TT relating to the activities of several of Kalhu's governors came to light.

The Governor's Palace archive

The building has yielded some 230 tablets, most of which were found in three neighbouring rooms (K, M and S) in the northern part of the palace. Room S also contained a collection of over 100 pieces of fine palace ware TT , nicknamed the "governor's dinner service" by the excavators, which rested on a mud-brick "platform" or "table" (Image 3). Cuneiform TT documents were found underneath this platform, which perhaps originally served as a sort of filing cabinet for the tablets. The administrative wing of Assurnasirpal II's PGP Northwest Palace used brick boxes for tablet storage, and a similar arrangement may have existed in the Governor's Palace. It would have been easy to fill in the boxes and convert them into a table when the tablets they housed were no longer needed.

Image 3: The beaker in the middle of this group of objects is one of the hundred or so pieces of pottery palace ware TT found in room S of the Governor's Palace. BM 1992,0302.185. Many other museums hold examplesincluding Cambridge's Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology View large image on British Museum website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The tablets are now known as the Governor's Palace archive, but in fact they represent a collection of often disparate texts rather than a single coherent archive. They fall into three main groups: private legal documents (found mainly in rooms K and M), administrative texts, and letters (both in room S). Some of the tablets were dated using the Assyrian system of eponyms TT (limmu). With the exception of a single text which dates from the reign of Shalmaneser III, the rest of the dated tablets cover the period between 802 and 710 BC. We do not know why there were no new tablets after this date. The end of the archive coincides with the completion of Dur-Šarruken PGP , Sargon II's PGP purpose-built royal capital, which for a brief period replaced Kalhu as the administrative centre of the Assyrian empire. Although Dur-Šarruken was abandoned as a capital after Sargon's death, Kalhu never regained its previous status and the capital was moved to Nineveh instead. The move to Dur-Šarruken was perhaps linked to the changes in the Governor's Palace, which apparently ceased to perform its earlier administrative function. This also seems to confirm that the palace was not the seat of the governor of Kalhu, at least at the end of the 8th century: if it had been, we might expect to find documents from his archive even after 710 BC, since the city of Kalhu continued to function as the provincial TT capital long after it lost the status of royal capital.

Image 4: Impression TT of a fine cylinder seal TT made of translucent chalcedony TT , found in room B which adjoined the ablution room (Image 2). The head of the excavation, Max Mallowan PGP , thought that it must have belonged to the governor of Kalhu himself, but there is no evidence to confirm this. Read a detailed description of the scene carved onto object BM 130865. View large image on British Museum website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The documents mention the names of five governors of Kalhu who held the office in the 9th and 8th centuries BC; some of the other tablets apparently belonged to members of the governors' households. As a result, the texts record a varied mix of private matters - such as property sales, receipts and loans - and official business in the form of administrative documents and correspondence (3). These help to shed light on the everyday activities of the governor. Among the more interesting letters is a complaint from the governor of Assur PGP to his colleague in Kalhu about a fire which resulted in the destruction of lands used for grazing: "Your subjects have set the desert on fire, and as far as the land of Suhu and as far as the land of Hadallu, it has eaten up the whole desert. Make enquiries... Who [ ] the fire?" (4)

Destruction and post-Assyrian occupation

The final days of the Governor's Palace are difficult to reconstruct since we have no textual sources after 710 BC, but the "governor's dinner service" found in room S seems to date from the very end of the Assyrian empire. This would suggest that the building - or at least parts of it - continued to be used into the late 7th century. When the Assyrian empire fell, the Governor's Palace was destroyed like many other buildings in Kalhu, such as Ezida and the Burnt Palace PGP . However, this did not deter squatters from making a home in its ruins, and even burying their dead there. The building continued to be inhabited into the Hellenistic TT period, when the central courtyard was turned into a burial ground.

Content last modified: 18 Dec 2019.

References

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB), pp. 133, Fig. 83. (Find in text ^)

- Mallowan, M.E.L., 1950. "Excavations at Nimrud. 1949-1950", Iraq 12, pp. 147-183 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. plate XXX, no. 1. (Find in text ^)

- Postgate, J.N., 1973. The Governor's Palace Archive (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 2), London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq (free PDF from BISI, 175 MB), pp. 16-23. (Find in text ^)

- Postgate, J.N., 1973. The Governor's Palace Archive (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 2), London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq (free PDF from BISI, 175 MB), pp. 187-188, no. 188. (Find in text ^)

Further reading

- Fales, F.M., 2012. "The Eighth-Century Governors of Kalhu: A Reappraisal in Context", in H.D. Baker, K. Kaniuth and A. Otto (eds.), Stories of Long Ago: Festschrift für Michael D. Roaf (Alter Orient und Altes Testament 397), Münster: Ugarit Verlag, pp. 117-139.

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB).

- Postgate, J.N., 1973. The Governor's Palace Archive (Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud 2), London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq (free PDF from BISI, 175 MB).

- Postgate, J.N. and J.E. Reade, 1976-1980. "Kalhu", Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 5, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 303-323.

Silvie Zamazalová

Silvie Zamazalová, 'The Governor's Palace', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thecity/thegovernorspalace/]