Ezida, the god Nabu's temple of scholarship

The god of wisdom's temple, Ezida, was at the opposite end of the royal citadel TT to the palace, next to the city governor's residence. It gained in importance over the 8th century BC and king Sargon II (r. 721-705 BC) remodelled it to reflect a close, triangular relationship between deity, royalty and scholarship. Royal āšipu-healers led scholarly activities in the temple, including the development of a large library of learned works.

The temple's early years

When Assurnasirpal II started on the renovation of Kalhu's citadel, Nabu's temple was one of the last buildings to be constructed—and not in the palace quarter b ut several hundred metres to the southeast. Assurnasirpal's numerous and extensive building accounts rarely mention Nabu's temple, and do so only in passing. Nabu, then, was only a peripheral member of Assurnasirpal's personal pantheon. It is now impossible to determine what his temple might have looked like at this time, as only traces of it survived later building work.

However, from its first days, Nabu's temple was a centre of scholarly activity. Ištaran-mudammiq PGP , Assurnasirpal's senior āšipu, wrote an ominous calendar for the library (CTN 4: 58). His descendants continued to be associated with the temple for at least four generations, as royal āšipus and royal scribes TT , writing incantations TT and omens TT (CTN 4: 8; CTN 4: 103).

One of a pair of divine attendant statues that stood at the entrance to Nabu's sanctuary (see isometric plan above). This statue arrived in London in 1856 (2) and is now displayed in Room 6 at the British Museum; its counterpart is in the Iraq Museum, Baghdad. BM 118889. View large image on British Museum website © The Trustees of the British Museum.

During the reign of Assurnasirpal II's grandson Adad-nerari III PGP (r. 810-783 BC) the old temple on the acropolis TT was demolished and a massive 3 metre-high mud-brick platform constructed for the new building to rest on (3). The solid walls, monumental statuary, and extensive use of large stone blocks in the foundation-courses TT and pavements all speak of considerable expense.

Curiously, however, Nabu's name hardly ever occurs in Adad-nerari's royal inscriptions, while conversely Adad-nerari's name is almost nowhere to be found in the temple. The only place it occurs is on two statues outside Nabu's shrine, which his city governor Bel-tarṣi-ilumma PGP dedicated to Nabu for the life of the king and the queen mother TT .

Even when the temple was renovated again in the late 8th century BC, no king claimed credit for the work. However, there is no reason to doubt Max Mallowan PGP 's carefully drawn conclusion that this work was carried out in the reign of Sargon II PGP (4).

The temple in its heyday

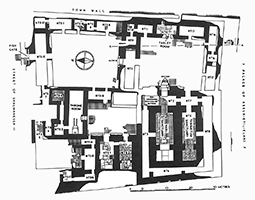

The twin shrines of Nabu and his consort Tašmetu PGP , the rooms around the adjacent inner courtyard, as well as the famous "Fish Gate" entrance to the north, were laid out in about 800 BC and then remained essentially unchanged. Just before 700 BC much of the northern part of the temple was built anew, and perhaps completely remodelled. It is essentially this version of Ezida that was used right until the end of empire and which excavators discovered in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The close relationship between Neo-Assyrian TT kingship, deity and scholarship is elegantly realised in the architecture of the Kalhu Ezida. The temple is entered via a monumental gateway that features colossal beneficent TT spirits in typical Assyrian style. But whereas most temples and palaces famously feature monumental winged bulls TT , Ezida's main entrance - the so-called "Fish Gate" - is flanked by giant mermen, originally covered in gold TT leaf (5), who represented the primordial sages TT who brought wisdom and civilisation to humankind in deep antiquity.

Off the temple's first courtyard, which was surrounded by primarily utilitarian offices, are two further courts. A large courtyard to the south gave access to the twin shrines of Nabu and Tašmetu, whose larger-than-life statues, and Bel-tarṣi-ilumma's protective figures at their gateways, could gaze directly on the scholars TT at work in and around the tablet store immediately opposite. A corridor around the back of the shrines perhaps enabled the priests to voice communications from the gods without being seen as the intermediaries.

This brown pebble was found among burnt debris in corridor NT3 opposite the entrance to Nabu's sanctuary. It has been inscribed with a dedication to Nabu and a priest figure standing in front of symbols of Nabu (a wedge-shaped stylus) and Marduk PGP (a triangular-headed spade) (6). ND 4304, Iraq Museum. View large image (145 KB).

To the west, a smaller courtyard led on to a small-scale throne room, complete with tracks for a brazier TT in cold weather, so that the king could visit with appropriate ritual TT and protocol. Nabu and Tašmetu could occupy miniature versions of the twin shrines right next to the throne room while the king was in residence.

Early 7th century records and letters show that this area of the temple was known as the bēt akiāte, the akītu TT -suite, which was set aside for an annual "sacred marriage TT " ritual between Nabu and Tašmetu. The ritual lasted several days and took place in the second month of the year (in late spring). A further room in the akītu-suite, which might have been called the bēt ūmē sebetti ("seven-day room"), may have served as their bedroom for the duration. Offerings made to the divine couple during this time were designed to prolong the life of the king and all of his descendants (7). Even if the king were unable to attend, the hazannu ("mayor") of Ezida was present throughout, to make offerings on the king's behalf (8).

Scholarly activity in the 7th century BC

Fully half of the 250-odd scholarly tablets found in a room immediately opposite his shrine bear omens, incantations and rituals—for advising the Assyrian king on political decision-making and for helping him to maintain his relationship with the gods. A further quarter comprise hymns and lexical works (standardised lists of words and cuneiform TT signs), while the majority of the remainder comprise medical, literary and calendrical writings.

Some 30 scholarly tablets of the Kalhu Ezida corpus have extant or partially surviving colophons TT , from which at least 15 names of scholars can be identified. Many of them belong to just two dynasties of Assyrian royal scholars. As we have seen, the earliest comprises several generations of the descendants of Ištaran-šumu-ukin PGP , a 10th(?)-century āšip šarri ("royal exorcist TT "). But by the late 8th century, it appears that they had been ousted or superseded by the descendants of Gabbu-ilani-ereš, ummânu ("chief scholar") of Assurnasirpal II (and thus Ištaran-mudammiq's contemporary).

When Sargon II inauspiciously died in battle in the summer of 705, and when - even more inauspiciously - his body was never found, his son and heir Sennacherib PGP ordered the court to move to Nineveh PGP for a fresh beginning. Sennacherib ignored Kalhu, commissioned no building work on any of Nabu's temples and never mentioned him in any of his copious royal inscriptions, except in occasional collective invocations to all the great gods for their blessings or curses. Yet even then, royal scholarship was not confined to Nineveh. Even the most trusted scholars came and went from court.

Nabu-zuqup-kenu PGP , scribe to both Sargon II and Sennacherib, wrote over 60 surviving scholarly tablets, nearly two-thirds of which explicitly state that they were written in Kalhu (9). However, the tablets themselves belong to the Kuyunjik collection TT of the British Museum, most likely meaning that they were excavated by Layard PGP and his associates from the royal citadel of Nineveh.

Arm of a throne once belonging to king Esarhaddon, found in Nabu's temple. The ivory was burned in antiquity, turning it a black colour. 1957.1+2, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford View large image on Ashmolean Museum website. © Ashmolean Museum.

Nabu-zuqup-kenu's sons, Esarhaddon's rab āšipi ("chief āšipu-healer") Adad-šumu-uṣur PGP and chief scribe Nabu-zeru-lešir PGP , are well attested in Assyrian court correspondence from Nineveh, sometimes in collaboration with the king's chief lamenter TT Urad-Ea PGP and other colleagues. But Adad-šumu-uṣur spent at least some of his time in Ezida at Kalhu, where he is documented performing a ritual against two types of fungi that had infested Ezida (SAA 13: 71). His nephew, the crown prince TT 's āšipu Šumaya PGP , petitioned for a move to Kalhu after the death of his father Nabu-zeru-lešir. That suggests that Nabu-zeru-lešir too was based in Ezida there.

And many of these men's tablets have been found in Nabu's temple. Adad-šumu-uṣur owned a tablet from the terrestrial omen TT series Šumma ālu ("If a city (is set on a height)") (CTN 4: 45). One of Nabu-zeru-lešir's son (possibly Šumaya) copied an ominous calendar "for the prolongation of his life" (CTN 4: 59). Further sons or descendants of Nabu-zuqup-kenu are mentioned in colophons of two tablets of physiognomic omens Alandimmû and another of unidentified omens (CTN 4: 74; 78; 89). Nabu-le'i PGP , son of Adad-šumu-uṣur's close associate Urad-Ea, was the scribe of a hitherto unidentified ritual (CTN 4: 187), which he "copied like its original for him to see".

The end

Ezida continued to function perhaps right until the end of empire. Assurbanipal PGP refurbished and re-roofed it "in glad singing and celebration", while Aššur-etel-ilani PGP (r. 630?-623? BC) carried out repairs to its east wall and akītu suite. At least for the first two decades of Assurbanipal's reign the temple gave out short-term loans of grain to local inhabitants in Nabu's name (10), and until 621* TT BC or later it received private votive TT gifts of slaves and land for Nabu as "scribe of the universe" or "scribe of Esaggila PGP " (SAA 12: 95–98). Such legal documents were witnessed by the temple's cultic and domestic - but not scholarly - personnel, as well as the royal representative (qēpu, lit. "trusted one").

A lack of dateable colophons TT prevents us from determining whether scholarly tablets continued to be written or deposited in the room opposite Nabu's shrine, but clearly several hundred were still in situ when the building ceased to function as a temple, presumably when the city fell in 614 BC. Likewise, copies of Esarhaddon's Succession Treaty of 672 BC, that had bound citizens, scholars and vassals TT to supporting the appointment of Assurbanipal and Šamaš-šumu-ukin PGP as his successors TT (SAA 2: 6), must have still been stored somewhere in the temple, or at least close nearby. The temple's looters smashed them to pieces in the throne room, along with much rich ivory TT furniture, some pieces of which—to judge by the style of their carvings - dated back to Sargon II or even Adad-nerari III's time (11), (12).

After a brief period of squatter occupation in its empty, roofless shell, during which time a bread oven was installed in Nabu's sanctuary, there were short-lived attempts to repair the shrine and revive its cultic functions (13). But there is no direct evidence for the worship of Nabu in post-Assyrian Kalhu.

Content last modified: 18 Dec 2019

References

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB), pp. 112, figure 67. (Find in text ^)

- Gadd, C.J., 1936. The Stones of Assyria: the Surviving Remains of Assyrian Sculpture, their Recovery and their Original Positions, London: Chatto and Windus, pp. 150-151. (Find in text ^)

- Mallowan, M.E.L., 1966. Nimrud and Its Remains, vols. I-II, London: Collins, pp. 261 (vol. I). (Find in text ^)

- Mallowan, M.E.L., 1966. Nimrud and Its Remains, vols. I-II, London: Collins, pp. 283-284 (vol. I). (Find in text ^)

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB), p. 111. (Find in text ^)

- Mallowan, M.E.L., 1966. Nimrud and Its Remains, vols. I-II, London: Collins, pp. 270, figure 252. (Find in text ^)

- Cole, S.W. and P. Machinist, 1998. Letters from Assyrian and Babylonian Priests to Kings Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal (State Archives of Assyria XIII), Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, pp. xv-xvi. (Find in text ^)

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB), pp. 119-123. (Find in text ^)

- Hunger, H., 1968. Babylonische und assyrische Kolophone (Alter Orient und Altes Testament 2), Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, pp. 90-95, nos. 293–311, of which nos. 293–294 and 305 name Kalhu. (Find in text ^)

- Parker, B. 1957. "Nimrud tablets, 1956: economic and legal texts from the Nabu Temple", Iraq 19, pp. 125-138 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers). (Find in text ^)

- Mallowan, M.E.L., 1966. Nimrud and Its Remains, vols. I-II, London: Collins, pp. 241 (vol. I). (Find in text ^)

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB), p. 199. (Find in text ^)

- Mallowan, M.E.L., 1966. Nimrud and Its Remains, vols. I-II, London: Collins, pp. 284-287 (vol. I). (Find in text ^)

Further reading

- Black, J.A., 2008. "The libraries of Kalhu", in J.E. Curtis, J. McCall, D. Collon and L. al-Gailani Werr (eds.), New Light on Nimrud: Proceedings of the Nimrud Conference, 11th-13th March 2002, London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq (free PDF from BISI, 22 MB), pp. 261-265.

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB), pp. 111-123.

- Parker, B. 1957. "Nimrud tablets, 1956: economic and legal texts from the Nabu Temple", Iraq 19, pp. 125-138 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers).

- Postgate, J.N., 1974. "The bīt akīti in Neo-Assyrian Nabu temples", Sumer 30, pp. 51-74.

Eleanor Robson

Eleanor Robson, 'Ezida, the god Nabu's temple of scholarship', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/ancientkalhu/thecity/nabustemple/]