Lexical Texts in Neo Assyrian Education

Lexical texts were used in the education of the crown prince at the House of Succession in Nineveh. His education consisted of both physical exercise and training in literacy and scholarly subjects. Assurbanipal claims in his inscriptions that he understood the most complex cuneiform texts, but other data suggest that his cuneiform skills may have been more modest.

Exercise texts, which we have in large numbers from Babylonia, have rarely been excavated in Assyria and practically none are known from Nineveh. For the reconstruction of the role of lexical texts in education we are, therefore, dependent on other types of evidence.

K 864 = SAA 8 41. Letter by Nabû-ahhē-erība with glosses in small characters squeezed between the lines. Photograph © British Museum, London

Indirect evidence for the methods of teaching elementary cuneiform comes from the glosses, in smaller script below the line, in letters to Assurbanipal by Nabû-ahhē-erība and (less frequently) by Balasî. The two scholars were both astrologers (ṭupšar enūma Anu Enlil); they worked as a team and belonged to the closest circle of advisers to the king and the crown prince. Balasî was the teacher of crown prince Assurbanipal (SAA 10, 39) and went on to become his chief scribe.

Several such glosses appear in the first three lines of a letter by Nabû-ahhē-erība published as SAA 8 41. The text reads as follows:

DIŠ

d30

TUR₃

GI₆

ṣa-al-muNIGIN

If the moon is surrounded by a black halo

ITI

ar-huA.AN

zu-un-nuu₂-kal

u₂-ka-laKI.MIN

IM.DIRI-MEŠ

ur-pa-a-tithe month holds rain. Variant: clouds

uk-ta-ṣa-ra will be gathered.

The text quotes an omen, using the technical orthography full of word signs (logograms) that is typical for omen texts. The glosses explain the logograms (writing them out in syllable signs) and other less common writings and are inserted between the lines (glossed words are in italics in the translation). The kinds of things that are explained are not very different from what one would expect in elementary word and sign lists. The example lines contain the following explanations:

| GI₆ | ṣa-al-mu | black |

| ITI | ar-hu | month |

| A.AN | zu-un-nu | rain |

| u₂-kal | u₂-ka-la | it holds |

| IM.DIRI-MEŠ | ur-pa-a-ti | clouds |

The glosses explain word signs, such as ITI = arhu (month) and sign values (the reading of the sign KAL is explained as ka-la). These are the kinds of explanations that one may expect in lists that were used all over Mesopotamia in the first millennium for elementary education. These lists are now called Syllabary A (Sa) and Syllabary B (Sb); many examples of library copies of those lists are attested in the Assurbanipal collection, but no actual exercise tablets have survived. The glosses in the letters to the king do not quote the lists, but they represent information in a way that builds upon the educational methods and traditions of the time.

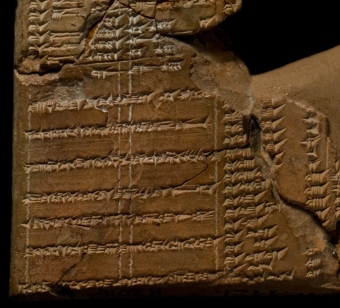

Colophon of K 2016A+, a copy of Ura 4 (list of wooden furniture and boats) written for consultation by the crown prince Assurbanipal. Photograph © British Museum, London

An interesting piece of evidence for (slightly) more advanced education is K 2016a+, which contains the fourth chapter from the thematic list Ura and provides words for wooden furniture and boats. The colophon of this tablet reads as follows:

Fourth tablet of the series Ura = hubullum.

For the consultation (tamrirtu) by Assurbanipal, the crown prince

of the succession house of Essarhaddon the king of the world, king of the land Assur,

governor of Babylon, king of the land Sumer

and Akkad, Aplāya, the junior apprentice scribe

the son of Kēni the scribe of the crown prince wrote it

and provided it for the crown prince his lord as a prayer.

This passage refers to the education of both crown prince Assurbanipal and Aplāya, the junior apprentice. Aplāya is asked to copy Ura 4 in its entirety in a quality that is suitable for use by the crown prince. Aplāya's connection to the crown prince runs through his father Kēni, who was scribe of the crown prince. What that title implied exactly is not known, but it may well have included instruction in scribal and scholarly matters. The crucial term here is tamrirtu, translated "consultation" above. The word derives from the verb murruru which is used for checking a passage in a reference text and in the present context may indicate that the tablet became part of a reference library for Assurbanipal's studies while he was a crown prince.

27 Dec 2019Further reading

- Livingstone, Alasdair 2007 Ashurbanipal: Literate or Not? Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 97: 98-118.

- Talon, Philippe 2003 The use of glosses in Neo-Assyrian letters and astrological reports. Pp. 648-65 in Semitic and Assyriological Studies Presented to Pelio Fronzaroli by Pupils and Colleagues, eds. Paolo Marrassini and Robert D. Biggs. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Villard, Pierre 1997 L'éducation d'Assurbanipal. Enfance et éducation dans le Proche-Orient ancien. Ktema 22: 135-49.

- Zamazalová, Silvie 2011 The Education of Neo-Assyrian Princes. Pp. 313-30 in The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, eds. Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson. Oxford: Oxford University Press..

Niek Veldhuis

Niek Veldhuis, 'Lexical Texts in Neo Assyrian Education', Royal Lexicography: Cuneiform Lexical Texts from Nineveh, The DCCLT Project, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/dcclt/nineveh/introduction/education/]