Imperial splendour: views of Kalhu in 1850

In 1850, the young British explorer Austen Henry Layard PGP had been tunnelling into the site of Nimrud, on and off, for the past five years. He had found a spectacular series of sculptures and other objects, and shipped them home to the British Museum TT . He had mapped the rooms of a series of palaces, which seemed to belong to the fabled Old Testament city of Nineveh PGP . Back in London, his lively writings and illustrations had captured the imaginations of the Christian establishment and the men of empire alike. It was now time to leave Nimrud behind for a new career in diplomacy — but the names of Layard and Nimrud would remain inseparable for a long, long time to come.

The view from Nimrud

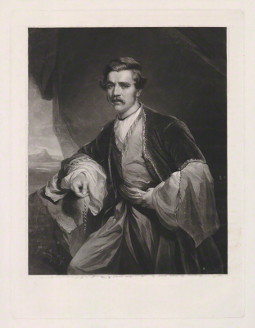

Image 1: This portrait of Austen Henry Layard PGP was made in 1850. It celebrates his adventures by depicting him in 'oriental' dress against an exotic background with Nimrud in the distance. The original oil painting, by Henry Wyndham Phillips PGP , was copied as this mezzotint TT engraving by Samuel William Reynolds Jr PGP , to enable its mass reproduction. NPG D37226, National Portrait Gallery, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0. View this image on the National Portrait Gallery's website.

Layard was not archaeologist as we would understand the term, but then very few people were in 1850. The idea of stratigraphic TT excavation, the systematic uncovering and recording of objects in context, layer by layer, was still very new and controversial (1). It seemed to work well for the prehistoric burial mounds uncovered in Danish peat bogs but in Britain the conditions of archaeological preservation meant that these methods were difficult to replicate. And there were already two highly respected methods for researching the past: the collecting of antiquarian TT objects, and the study of ancient classical and biblical sources. These were both prestigious activities that were well established in the fabric of British intellectual life and would take many decades to dislodge. Layard was not an expert in either of these fields either — just a young man wanting to make a name for himself. But he had good contacts, and a lot of initiative and ambition.

So Layard followed the precedent of British antiquarians by tunnelling for artefacts in the ground. The idea that fieldwork consisted of finding specimens abroad, then shipping them home for research and display, was quite usual in early nineteenth-century Europe. Some people dug for geological samples, others picked exotic flowers or trapped wild animals for London's various museums and research institutions. In fact, Layard's closest inspiration and rival, Paul-Émile Botta PGP , was a natural historian TT by training. He had been posted to Mosul PGP as the first French consul-general TT in order to dig for antiquities, just as he had hunted for butterflies or caught snakes for collectors in Paris, earlier in his career (2).

Image 2: Mid-nineteenth century readers of Layard's books must have marvelled at the thought that the remains of a once-mighty empire could be discovered in such apparently unremarkable hills. To add visual interest to this view of NImrud from the west, the engraver has foregrounded local men, a nomads' encampment and a small cemetery (3). View large image.

Layard's Nimrud, then, was a dark and mysterious place, buried in a hillside (Image 2). It was delineated by the carved stone bas-reliefs TT that lined the walls of the palaces, and populated with artefacts that were attractive and portable enough to be shipped to England for art historical analysis and display. In Layard's Nimrud archaeological artefacts such as mud-brick walls and cuneiform TT tablets TT were invisible. He and his workers could not distinguish them from the earth through which the men tunnelled. And the high mound at the northern end of the site was just a mound. No-one knew about ancient ziggurats in 1850, and the Old Testament story of the Tower of Babel was just a story (Gen 11:1–9).

Layard did find cuneiform inscriptions, on the stone sculptures in the palace, but they were bafflingly complex. In 1850 only a handful of men had pretensions to understanding the script, and they were still several years away from agreeing that the principles of decipherment had in fact been achieved. As a well brought up Church of England TT man, if not a particularly devout believer, Layard therefore had to take the Old Testament as his primary guide to the ancient Middle Eastern past.

Even the ancient city of Kalhu was invisible to Layard. Like his contemporaries, he saw only the Biblical city of Nineveh. The Book of Kings, Isiaiah, Nahum and of course Jonah, are replete with references to Nineveh. Indeed it had been local veneration of Jonah's tomb PGP that had attracted Europeans to start exploring the ruin mounds around Mosul a generation or two before. For Layard, as for his predecessors and contemporaries, Nimrud, and the similar sites of Kuyunjik PGP and Khorsabad PGP , were all districts of ancient Nineveh, "an exceedingly great city of three days journey in breadth", in the words of Jonah himself (Jon 3:3). As Kouyunjik, where Layard had also been working, and Khorsabad, Botta's main excavation site, were yielding apparently very similar finds, then this all made perfect sense.

The view from London

Image 3: Later editions of Layard's hugely popular account of his discoveries at Nimrud and Kuyunjik PGP became known simply as Layard's Nineveh, encapsulating the public's identification of the man with the site, and the site with the biblical city (4). Note the cuneiform-like lettering on the cover, evoking a script that could still barely be read. View large image.

If the ancient city was hard to discern in the gloomy chaos of the excavation mound, it came brilliantly alive in London. Finds from Nimrud began to arrive at the British Museum in 1847, and attracted huge amounts of attention and debate. Mid-Victorian Britain was soaked in Biblical scripture and fascinated by tangible evidence of its reality. Here, at last, were the remnants of a real-life Biblical city — and an excitingly corrupt and decadent one at that. According to your Christian interests, you could use Nimrud to sermonise about sinfulness, extol the glories of imperialism, or simply marvel at its exoticism and antiquity.

People who could not go to London to see the sculptures and other objects for themselves could read about them instead, and look at pictures (Image 3). Layard had no cameras on site, despite Henry Fox Talbot's PGP deputations to the British Museum that he should. He preferred to rely on the more tried and tested methods of artists' sketches to illustrate his often self-aggrandising narratives of his adventures and discoveries. The technologies of reproduction may have been monochrome but Layard's anecdotes were addictively technicolour in their vivacity and realism. His books on Nimrud, from cheap railway editions to luxury folios, sold wildly well. Many other authors were keen to jump on the Assyrian bandwagon too (5).

Between 1847 and 1850, the popular middlebrow weekly The Illustrated London News TT carried no less than nine separate reports of artefacts from Nimrud arriving at the British Museum, usually handsomely illustrated. The bumper Christmas edition for 1850, otherwise filled with Dickensian PGP jollity, presented the latest arrivals as very much in the same spirit. They would "undoubtedly prove attractive to Christmas visitors to the Museum," the author opined (6).

Image 4: Soon after the arrival of sculptures from Nimrud at the British Museum, the popular weekly Illustrated London News TT singled them out as "foremost amongst the novelties at this truly national establishment, and especially fitted for the gratification of holiday visitors" over the 1850 Christmas break (7). The well dressed visitor shown next to this winged genie TT certainly looks pleased to meet a like-minded fellow. © Gale. View large image.

The following week, in the New Year edition, a (much enlarged) winged genie TT made eye contact with a dapper man-about-town, their body-language and demeanour suggesting mutual approval and comfort in each other's company (Image 4). This image of clubbable geniality was in sharp contrast to the portrayal of rough and ready San Francisco on the immediately preceding page, grouped with desert Bedouin and artefacts from a deposed Indian sultan. It is clear where the boundaries of civilisation were thought to lie (8).

Indeed, as historians such as Fred Bohrer, Stephen Holloway and Timothy Larsen have extensively shown, educated Britons flocked to the news stands, the book shops and the British Museum to catch a glimpse of Biblical Nimrud because it resonated with modern experience (9), (10), (11). In 1850 Britain was at the heart of an unprecedentedly extensive, hugely profitable and technologically innovative naval empire. In ancient Assyria they chose to see a highly effective precursor, whose eventual downfall could be ignored or attributed to its heathen brutality. In this light, Layard's next step, a move into politics and diplomacy, was a natural career progression.

18 Dec 2019References

- Rowley-Conwy, P., 2007. From Genesis to Prehistory: the Archaeological Three Age System and its Contested Reception in Denmark, Britain, and Ireland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Find in text ^)

- McGovern, F.H. and McGovern, J.N., 1986. "'BA' portrait: Paul-Émile Botta", The Biblical Archaeologist 49: 109–13.. (Find in text ^)

- Layard, A.H., 1849-1853. The Monuments of Nineveh: From Drawings Made on the Spot, vols. I–II, London: John Murray (free online edition of vol. 1 and vol. 2), pp. I pl. 98. (Find in text ^)

- Layard, A.H., 1849. Nineveh and its Remains, London: John Murray (free online edition at The Internet Archive). (Find in text ^)

- Malley, S., 2012. "Nineveh 1851: an archaeography", Journal of Literature and Science 5: 23–37. (Find in text ^)

- The Illustrated London News, 21 December 1850. (Find in text ^)

- The Illustrated London News, 28 December 1850, p. 505. (Find in text ^)

- The Illustrated London News, 28 December 1850. (Find in text ^)

- Bohrer, F., 2003. Orientalism and Visual Culture: Imagining Mesopotamia in Nineteenth-Century Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Find in text ^)

- Holloway, S.W., 2001. "Biblical Assyria and other anxieties in the British Empire," Journal of Religion & Society 3: 1-19 (free PDF from JRS [http://moses.creighton.edu/jrs/2001/2001-12.pdf]). (Find in text ^)

- Larsen, T., 2009. "Austen Henry Layard's Nineveh: the Bible and archaeology in Victorian Britain'", Journal of Religious History 33: 66–81. (Find in text ^)

Further reading

- Bohrer, F., 2003. Orientalism and Visual Culture: Imagining Mesopotamia in Nineteenth-Century Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brusius, M., 2012. "Misfit objects: Layard's excavations in ancient Mesopotamia and the Biblical imagination in mid-nineteenth -Century Britain", Journal of Literature and Science 5 (2012): 38–52 (free PDF from JLS [http://www.literatureandscience.org/issues/JLS_5_1/JLS_vol_5_no_1_Brusius.pdf]).

- Díaz-Andreu, Margarita, A World History of Nineteenth-Century Archaeology: Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Past, Oxford University Press, pp. 131-166.

- Larsen, M.T., 1996. The Conquest of Assyria: Excavations in an Antique Land, London: Routledge.

- Malley, S., 2012. From Archaeology to Spectacle in Victorian Britain: the Case of Assyria, Farnham: Ashgate.

- Rowley-Conwy, P., 2007. From Genesis to Prehistory: the Archaeological Three Age System and its Contested Reception in Denmark, Britain, and Ireland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eleanor Robson

Eleanor Robson, 'Imperial splendour: views of Kalhu in 1850', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/modernnimrud/onthemound/1850/]