In the headlines, out of bounds: Kalhu in 2015

Right now, in the summer of 2015, the name of Nimrud is better known globally than at any time before. Yet the site itself is under jihadi occupation and the Northwest Palace has been destroyed. Archaeologists, museum staff and university academics in nearby Mosul PGP have been forced from their jobs, and many have fled to safer places. Only when Da'esh/ISIS TT has been expelled from northern Iraq will it be possible to truly assess its current state. Meanwhile new computer-based techniques can help to prepare for restoration TT and a for new phase of Iraqi and international research.

The view from the mound

Image 1: This winged lion TT was one of a pair from Nimrud that had been removed to the gallery of Mosul Museum to protect it from further damage. On its base, a bored Assyrian door attendant had carved a board game to play in quieter moments of his guard duty. The current state of the statue, since Da,'esh's destructive rampage through the museum, is known. Photo by Eleanor Robson, March 2001. View large image.

Image 2: Using conventional digital photos like Image 1, volunteer members of Project Mosul have been creating 3D virtual reconstructions of objects feared lost or damaged from Mosul Museum. A contributor with the username BrittInv made this model with Sketchfab in May 2015. View BrittInv's model of the winged lion on Sketchfab.

In the mid-90s, under UN sanctions TT , Nimrud's site guards had been unable to prevent the theft of sculptural bas-reliefs TT from Tiglath-pileser III's PGP Central Palace PGP from an onsite storehouse. Two of of those pieces then appeared on the London art market and their current whereabouts is unknown (1). But the site survived the 2003 Iraq War TT intact, and the local staff also managed to protect it well in the chaotic months and years that followed. All was well for Muzahim Mahmoud PGP and his team, if quiet without international visitors or collaborators, until the summer of 2014.

When Da'esh/ISIS invaded northern Iraq in late June 2014 it soon became obvious that area's rich cultural heritage TT was under grave threat from the extremist occupiers. Mosul Museum TT had left most of its holdings in safe storage near Baghdad PGP since before the 2003 war but 93 particularly immovable objects, including sculptures from Nimrud, were still on display in the public galleries (Image 1, Image 2). Nevertheless, the director put the museum into lockdown. At the University of Mosul, Da'esh declared most of the arts and humanities departments to be "unislamic" and closed them down. Their academic staff, including archaeologists and Assyriologists TT , lay low or fled.

For a few months after the invasion, Iraq's central government stopped the payment of its employees in ISIS-occupied areas. Unfortunately that included archaeological site guards, leaving Nimrud vulnerable to looting. In the interim BISI TT stepped into the breach, with a complicated money transfer to the head of security. But that was only after a criminal gang had managed to prise three bas-reliefs from the palace.

The view from the news media

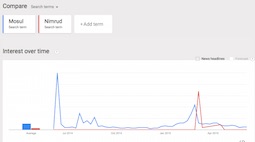

Image 3: International news media's coverage of ISIS's destruction of the Northwest Palace was intense but short-lived. This Google Trends charts shows high interest in the invasion of Mosul in June 2014, followed by ongoing concern for its non-Sunni inhabitants. Twin peaks for Mosul and Nimrud in late February-early March 2015 capture responses to Da'esh propaganda videos. View full page on Google Trends.

For the first months of the occupation, Da,'esh concentrated its attentions on the subjugation and cultural eradication of northern Iraq's living population and left archaeological heritage largely alone. But in early 2015 they discovered the propagandistic power of iconoclasm. A video showing ISIS men smashing the remaining sculptures in Mosul Museum quickly attracted worldwide attention. A few weeks later a follow-up video depicted an aborted attempt to deface the supposedly idolatrous TT bas-reliefs TT still in situ in the Northwest Palace, culminating in the full scale demolition of the whole structure with explosives.

For a few days Nimrud was in the headlines all over the world. Commentators wrung their hands over the barbarian destruction of ancient civilisation, sometimes without fully understanding what had been lost. But it was impossible to report from the ground or even to judge the extent of the damage from aerial imagery, which was tightly guarded by military and archaeological authorities from fear of provoking more attacks. So in the absence of concrete evidence from non-Da'esh sources the story soon fell out of the news cycle and currently remains quiet (Image 3).

New views of Kalhu from new technologies

Image 4: Sam Paley's PGP pioneering 3D virtual reconstructions of the Northwest Palace are now hosted by a not-for-profit organisation called Vizin. Here we look east down the throne room, as a visitor approaches the enthroned king. © Learning Sites, Inc. View this image and others on the Vizin website.

The good news, such as it is, is that data and methods already exist that will help to restore order to Nimrud when the time is right, that will compensate to some extent for the losses it has sustained, and which will open up new avenues of research and education.

In the early 1990s, American archaeologist Sam Paley PGP began to create a Virtual Reality reconstruction of the Northwest Palace, based on work that he and Polish colleagues Janusz Meuszyński and Richard Sobolewski PGP had done together (2), (3), (4). The project has been through many incarnations as the technology has evolved over the past two decades and the original team members have passed away (5). But the latest published results, from 2011, are impressive (Image 4).

Image 5: Factum Arte have physically recreated the decorative scheme of the throne room. Their technicians visited all the collections now holding relevant Nimrud sculpture in order to create detailed 3D scans. Here we see them at work in the British Museum's TT Nimrud galleries. Other team workers then created life-size replicas made of plaster and of imitation marble TT . © Factum Arte. View this image in context on the Factum Arte website.

More recently a European company called Factum Arte has developed a method of making life-size physical facsimiles of the Nimrud reliefs. They have also created a new synthetic material called scagliola that imitates Mosul marble TT very effectively. Members of its staff spent a decade travelling the world's museums to make 3d scans of bas-reliefs from the throne room of the Northwest Palace (Image 5). In May 2014 they delivered a full-scale replica of the eastern, throne, end of the throne room to the University of Mosul's newly built Institute for Cuneiform Studies. Just a few weeks later, the city was overrun by Da'esh and it is not known what has happened to it. But that is the least of Mosul's worries for now, and the casts can be reproduced.

Rather more prosaically, standard digital photography has enabled collections all over the world to present their Nimrud artefacts online. We have gathered all we can find in the Catalogues section of the site. And, aware of the limitations of Mallowan's PGP publications, the British Institute for the Study of Iraq TT is beginning a project to digitise the original dig records too — notebooks, photos, plans and slides — in the hope that these will form the backbone of future reconstruction efforts.

18 Dec 2019References

- Russell, J.M., 1997. "The modern sack of Nineveh and Nimrud", Culture without Context (Newsletter of the Illicit Antiquities Research Centre) 1. Read online. (Find in text ^)

- Meuszyński, J., 1981. Die Rekonstruktion der Reliefdarstellungen und ihrer Anordnung im Nordwestpalast von Kalḫu (Nimrūd), I: Räume: B.C.D.E.F.G.H.L.N.P. (Baghdader Forschungen 2), Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern. (Find in text ^)

- Paley, S.M. and R.P. Sobolewski, 1987. The reconstruction of the relief representations and their positions in the Northwest-Palace at Kalḫu (Nimrūd), II: Rooms I, S, T, Z, West wing (Baghdader Forschungen 10), Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern. (Find in text ^)

- Paley, S.M. and R.P. Sobolewski, 1992. The reconstruction of the relief representations and their positions in the Northwest-Palace at Kalḫu (Nimrūd), III: the principal entrances and courtyards (Baghdader Forschungen 14), Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern. (Find in text ^)

- Paley, S.M., 2008. "Creating a virtual reality model of the North-West Palace", in J.E. Curtis, J. McCall, D. Collon and L. al-Gailani Werr (eds.), New Light on Nimrud: Proceedings of the Nimrud Conference, 11th-13th March 2002, London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq (free PDF from BISI, 22 MB), pp. 195-208. (Find in text ^)

Further reading

- Robson, E., "Modern war, ancient casualties", The Times Literary Supplement, 25 March 2015. Read online.

Eleanor Robson

Eleanor Robson, 'In the headlines, out of bounds: Kalhu in 2015', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2019 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/modernnimrud/onthemound/2015/]