You are seeing an unstyled version of this site. If this is because you are using an older web browser, we recommend that you upgrade to a modern, standards-compliant browser such as FireFox [http://www.getfirefox.com/], which is available free of charge for Windows, Mac and Linux.

The Archives of Duri-Aššur and an Egyptian Family from Assur (WVDOG 152)

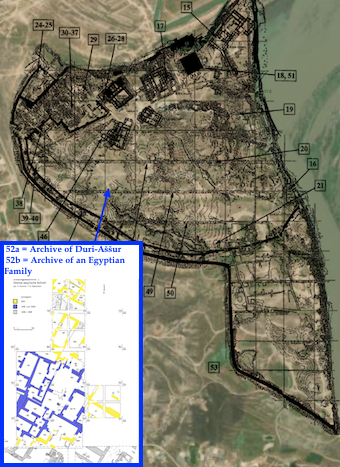

Satellite image of the ruins of Assur overlaid with a general plan of the archives and libraries (Pedersén, Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East 1500-300 B.C. p. 133 Plan 62) and showing the location of the archives of Duri-Aššur and an Egyptian family (plan from Projekt Assur West [https://www.assur.de/Themen/PublAssWest/publasswest.html]). Image prepared by Jamie Novotny.

This sub-project of the Archival Texts of the Assyrian Empire (ATAE) [/atae/index.html] Project includes open-access versions of the ninety-six Neo-Assyrian texts (with German translations) edited by Karen Radner in Peter Miglus, Karen Radner, and Franciszek M. Steępniowski, Ausgrabungen in Assur: Wohnquartiere in der Weststadt, Teil 1 (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 152), Wiesbaden, 2016.

The Archive of the Wine Merchant Duri-Aššur

This archive consists of legal documents, letters and lists excavated in a private house in 1990 and 2000–01 during German excavations headed by Barthel Hrouda (1990) and Peter Miglus (2000–01). The house is located in the middle of Assur and provides ca. 150 square meters of living space — in the ancient city's densely built-up urban environment, this was a very respectable size for a private house. The building belonged to a man called Duri-Aššur ("My fortress is the god Aššur") and served as the logistics center of one of the many private trading companies operating out of Assur. All the city's citizens were exempt from taxes, including "harbor, crossing and gate fees on land or water" and this significantly reduced the cost of importing goods and made trading an attractive enterprise. According to the texts of the archive, the wine firm was active from 651 BC until the Medes conquered the city of Assur in 614 BC: some of Duri-Aššur's letters had not yet been opened when his house went up in flames. The ensuing wars not only terminated the firm's activities but interrupted transregional trade on a large scale while the spoils of the Assyrian Empire were divided up between the Babylonian, Median and Egyptian armies.

The documents found in Duri-Aššur's house show that he and three partners (called "brothers") organized trade with the northern regions of the Assyrian Empire. Duri-Aššur himself oversaw the logistics of the company in Assur while his partners travelled to oversee their business activities. The firm employed four caravan leaders who each conducted three trips per year. They travelled upstream along the Tigris with donkeys laden with the silver needed to make the purchases as well as merchandise from Assur: hats, shoes and exclusive textiles, which also served as packing material for supplies and money. The destination of these donkey caravans was Zamahu in Jebel Sinjar in the border region between Iraq and Syria, famous for its wines. Once there, everything was sold, including the donkeys, and Duri-Aššur's agents bought wine with the proceeds, topped up with the silver funds. The wine was filled into animal skins (sheep, goat; rarely cattle). The wineskins were bound together with logs to create rafts for the return journey to Assur on the Tigris. This was good for the wine, as the river kept it cool and prevented it from spoiling. Back in Assur, all components of the raft constituted valuable merchandise: the wineskins with their valuable content, but also the logs which were much in demand as building timber in forestless Assur.

Carved gypsum wall panel relief from the North Palace at Nineveh (Kuyunjik) showing a garden scene with Ashurbanipal and his queen drinking wine. BM 124920. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Wine drinking was very common among the well-heeled inhabitants of Assur in the 7th century BC. From the 9th century onwards, the integration of wine-producing regions along the southern flank of the Taurus range into the empire had allowed wine consumption to spread beyond the palace and the temples where wine had long been part of the ritual meals served to the Assyrian gods. For the private consumers in Assur, wine had to be procured over considerable distances and was an expensive luxury. The solution was to invest in firms like that of Duri-Aššur, with guaranteed shares of the wine imports in return for silver paid upfront. The firm had a base of loyal customers with repeat investments who presumably kept their wine cellars well-stocked in this way. Although some investors contributed substantial sums of money, most of the amounts invested were quite small, sometimes just a fraction of a shekel of silver. The investment lists in Duri-Aššur's archive allow a glimpse into the composition of Assur's wine-loving population in the late 7th century BC: mostly craftsmen and administrative personnel in the service of the temple of the god Aššur, but also city officials and affiliates of the households of members of the royal family who maintained residences at Assur. A large number of women invested in the wine firm, and most of them were identified as Egyptian. Egyptian men, too, were among the customers and their presence is not surprising, given that the house right next to Duri-Aššur belonged to an Egyptian family.

The Archive of an Egyptian Family

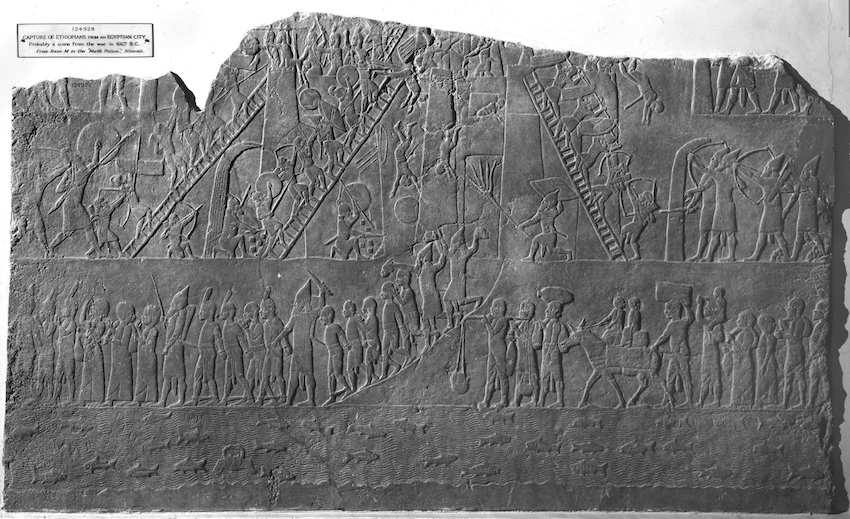

The family of Egyptians living in the house adjoining that of Duri-Aššur was one of many settled in the city of Assur after the conquest of Memphis in 671 BC. All their texts are legal documents and date to the reign of Ashurbanipal [/rinap/rinap5/] (r. 668–ca. 631 BC), specifically the period from 658 BC to the end of his reign. When Assyria was conquered in 614 BC the small archive was no longer in used and had been stored in such a way that the clay tablets were not fired by the blazes destroying the surrounding buildings. Consequently, the tablets are all unbaked and therefore in much poorer condition than the texts from Duri-Aššur's archive – in part because of general environmental influences and in part because of the process of excavation, during which the upward-facing side of some tablets was troweled off, leading to the loss of the text inscribed.

Gypsum wall panel relief depicting the Assyrians capturing a city in Egypt and deporting its inhabitants. BM 124928. © Trustees of the British Museum.

In addition to various judicial documents and debt notes (among others, for an "Egyptian who had fled the city (and) from Assyria", see IM 124734 = Ass 1990-120 [/atae/wvdog152/P514214]), the small archive of 15 texts contains a very poorly preserved document relating to a marriage (IM 124729 = Ass 1990-115 [/atae/wvdog152/P514216]), as well as an obligation to reimburse grain for certain sacrifices undertaken on behalf of the Assyrian king (IM 124741 = Ass 1990-127 [/atae/wvdog152/P514210]). Many people attested at Assur have Egyptian names but not all people of Egyptian lineage also had Egyptian names, as illustrated by the case of the "Egyptian Kiṣir-Aššur son of Urdu-Nabû" (IM 124734 = Ass 1990-120 [/atae/wvdog152/P514214]): he and his father bear widespread and completely inconspicuous Assyrian names. The small archive also highlights the remarkable financial and legal independence of the women of Egyptian origin attested Assur, as illustrated also by the investment ledgers from Duri-Aššur's archive.

The texts have been published by Karen Radner in Peter Miglus, Karen Radner, and Franciszek M. Steępniowski, Ausgrabungen in Assur: Wohnquartiere in der Weststadt, Teil 1 (Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 152), Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2016, which can be bought here [https://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de/Ausgrabungen_in_Assur._Wohnquartiere_in_der_Weststadt/titel_202.ahtml]. For a discussion of Duri-Aššur's archive, on which the sketch offered here is based, see: Karen Radner, Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 57–60. For more on the Egyptians who settled in Assur after being deported from Memphis in 671 BC and forcefully relocated population groups in the Assyrian Empire, see Karen Radner, "The 'Lost Tribes of Israel' in the context of the resettlement programme of the Assyrian Empire," in S. Hasegawa, C. Levin and K. Radner (eds.), The Last Days of the Kingdom of Israel (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 511), Berlin 2018, pp. 101–123.

Click here [/atae/wvdog152/pager] to browse the WVDOG 152 corpus.

ATAE is a key component of the Archival Texts of the Middle East in Antiquity (ATMEA) sub-project of the LMU-Munich-based Munich Open-access Cuneiform Corpus Initiative [https://www.en.ag.geschichte.uni-muenchen.de/research/mocci/index.html] (MOCCI; directed by Karen Radner and Jamie Novotny). Funding for the ATAE corpus project has been provided by LMU Munich and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (through the establishment of the Alexander von Humboldt Chair for Ancient History of the Near and Middle East).

For further details, see the "About the project" [/atae/abouttheproject/index.html] page.

Karen Radner

Karen Radner, 'The Archives of Duri-Aššur and an Egyptian Family from Assur (WVDOG 152)', Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 152, Assur: Wohnquartiere in der Weststadt, Teil 1 (WVDOG 152). Original publication: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2016; online contents: ATAE/WVDOG 152 Project, a sub-project of MOCCI, 2023 [http://oracc.org/atae/wvdog152/]